The scope of English in India includes Arundhati Roy and Kiran Desai, whose most recent books have been named as two of The New York Times’ ten books of the year, and the Amazon delivery man who understood the one-time password I had to give him better in English numbers than their Hindi equivalents. Snigdha Poonam has written of the growing cottage industry in English learning and teaching in India in her book, Dreamers, as young Indians not socialised into English try to acquire functional fluency in the language spoken by the country’s elites.

English is an Indian language but it is so joined at the hip with status and power that the English public sphere in India — the zone of discourse created by a language in which ideas are exchanged in the media, in educational institutions, in bookshops and cafés, where public opinion is shaped — has a curious presence. The public sphere of any language is likely to be an unequal place because that is the nature of human society, but the English public sphere in India is a little like a levitating bubble. Unlike a bubble, it is resilient and in no danger of popping but it does tend to float above the vast majority of the people that it discusses, makes policy for and creates public opinion about; the public that it addresses consists of the Indian people minus everyone who doesn’t speak or read English. Numerically, this is still a lot of people because India is a massive country, but it is still a very small fraction of the country’s population.

This is not unique to India; all formally colonised countries tend to be administered by a class descended from formerly collaborating elites fluent in the language of the colonising country. What is interesting about the Indian instance is the ability of its anglophone elite to create and sustain an English-speaking world that is to some degree independent of the English-speaking world of the West where newspapers like The New York Times make canonical judgments about culture and history and politics.

English-language publishing houses in India publish fiction and non-fiction for a mainly Indian audience. For the most part, being published in India is not contingent on the book being accepted elsewhere in the West. The oeuvre of the hugely influential Subaltern Studies Collective was published by publishing houses in India long before it found an audience abroad. Some of these publishers were affiliated with Western university presses and publishing houses, like the Oxford University Press and Penguin, but their Indian arms functioned as editorially autonomous organisations. The role of OUP India, Permanent Black, Kali for Women and Seagull Books, to name just a few, in creating a circumstance where Indian writers and scholars could publish for Indian readers without looking over their shoulders at editors and publishers Elsewhere

helped build an English public sphere local to India. But for them, the history of South Asia and subcontinental fiction in English, to take just two kinds of writing, would be less various and rich.

That said, the siloed nature of the English public sphere in India and its distance from adjacent Indian languages is, or ought to be, startling. There is a kind of apartheid that exists in metropolitan culture where English speakers and writers and ‘creators’ inhabit separate spaces. Seminars, panels, conferences, think tanks, book discussions, and bookshops are fairly rigidly divided by language. This is probably truer of Delhi and Mumbai than it is of Calcutta or Kochi, but I don’t think it’s controversial to say that there is remarkably little crossover between the public spheres of English and other Indian languages.

Generationally, this separation seems to be growing. I can testify to this in an anecdotal way. My aunt, who was a lecturer in Hindi in the University of Delhi, translated fiction and non-fiction from Bengali and Urdu into Hindi. Her shelves were, therefore, filled with books in English, Hindi, Bengali and Urdu. My father, who used to half-jokingly say that he spoke English in five Indian languages, had a study piled high with books in scripts I couldn’t read. In his retirement, he attempted a history of modern printing and publishing in India which resulted in shelves that illustrated the difference between his multilingual world and the monoculture I voluntarily inhabited.

Ramachandra Guha has written about this tendency towards the English-only desi intellectual and it’s important to say here that there are many first-rate minds in India that traffic in several languages. But it is possible to discern a trend, to see that bilingual scholars and writers tend to produce their important work in English. Girish Karnad, Vijay Tendulkar, U.R. Ananthamurthy and Mahasweta Devi are obvious exceptions to this rule. Geetanjali Shree and Banu Mushtaq, both of whom won the International Man Booker Prize for their fiction, carry this tradition forward; they might even presage a change, given the long overdue attention and admiration that the prize has brought in its wake.

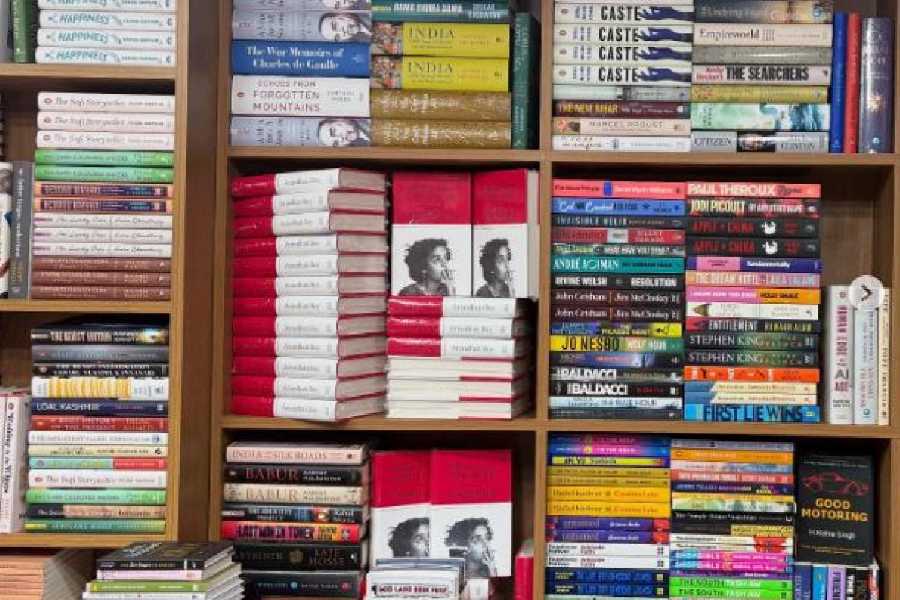

But it is still worth saying that the bookshop I visit offers Tomb of Sand, the translation of Geetanjali Shree’s Ret Samadhi, not the original. This is because the bookshop only stocks English language books. In this it isn’t exceptional; apart from railway station bookstalls, every bookshop in Delhi that sells English books only sells English books. In the heart of Hindi’s heartland, there is never any sign of the Nagari script. Through my reading life in Delhi, I’ve only once encountered a bookshop that stocked English books alongside whole shelves of books in Hindi. It closed after a few gallant years and thereby hangs a lesson.

The exclusion of Hindi books isn’t the fault of the bookshop owners; it is down to their clientele. People like me don’t buy books in Hindi. Amitabha Bagchi, who writes novels in English, has spoken of the sense of intimacy he experiences when he reads Hindi novels. Why do English readers who know Hindi deny themselves that pleasure? I can only imagine that the cachet of English and a lack of practice are part of the answer. In Bangalore, I imagine, there are nominally bilingual Kannadigas who, likewise, never buy a book in Kannada. In my generation, this wasn’t wholly true of middle class Bengalis. Bengali contemporaries in college used to write letters home to their parents in Bangla and even if the books they were reading in their hostel rooms were all in English, they always claimed familiarity with the Bengali canon. Anecdotally again, their children seem to be lost to English.

If anything, the alienation from desi first languages seems to be accelerating in this thin demographic. The new, expensive, international schools are designed to physically export their young customers to the Western metropolis, not merely to culturally alienate them. It’s worth reminding ourselves that in a digital environment where content is increasingly consumed visually and aurally, gatekeeping an exclusively English public sphere is a doomed enterprise. In a world where an online influencer like Dhruv Rathee and a YouTube anchor like Ravish Kumar reach millions more people than the best-known anglophone intellectuals, this exclusivist, incurious enclave courts irrelevance. Like all bankrupts, we risk going out of business, first gradually and then all at once.

mukulkesavan@hotmail.com