What does it mean to be a modern country? There are two defining aspects of modernity. One is the entry of the masses as conscious social and political actors. That signifies the ascendance of mass culture and mass politics. In this sense, the promise of modernity, from the French Revolution to India’s own anti-colonial struggle, lay in the seeding of a society where ordinary people (as opposed to traditional elites) become active participants in shaping the terms and the conditions of their

own lives. The second aspect of modernity lies in the systematic use of science and technology as instruments for collective transcendence, deployed to control the environment, resolve social problems, and build national power.

The signs that our tryst with modernity has ended up in an ugly cul-de-sac are everywhere. Quite literally, they are in the very (poison-laced) air that we breathe. To live in North India today means not only learning to forget the difference between wheezing and breathing but, worse, to resign yourself to watching your family members fall sick one by one from the dark, dystopian mist around you.

It is a problem which is felt by almost everyone, across the classes, but finds no expression in mass politics, save for the occasional feeble demonstration. Meanwhile, the mighty Indian State, after a decade of failure at combating surging pollution in its capital city, swerves between high-tech hare-brained schemes (the failed cloud-seeding experiment, to cite one example) and low-tech hare-brained schemes (sprinklers on trucks and a ban on restaurant tandoors).

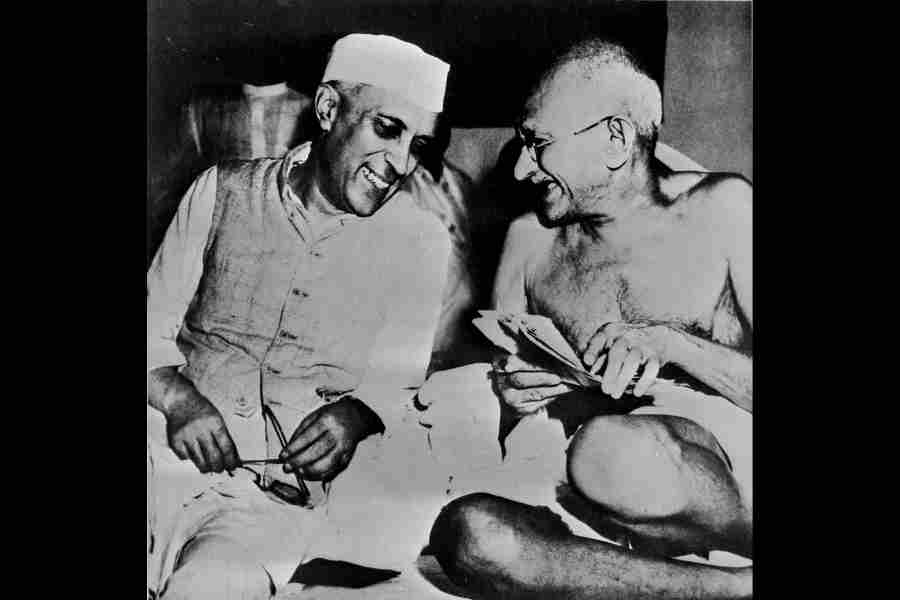

It is easy to forget that the country, in its adolescence, carried the air of a society charging towards the promised land of modernity. The present regime’s relentless efforts to disfigure the legacy of the two great icons of that quest — M.K. Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru — stem from a desire to sever the cultural tissue that binds us to their emancipatory projects. The Quit India movement had shown the impressive ability of Indian students, workers and peasants, fired up by the Gandhian ethos, to carry forward a pugnacious mass movement without the direction of the Congress leadership (all of its leaders were in prison). “A cursory glance at the movement shows that the Quit India campaign was a popular nationalist upsurge that started in the name of Gandhi but went substantially beyond any confines that Gandhi may have envisaged,” wrote Bidyut Chakrabarty in his biography of Gandhi. Having seen the Indian people rise up to assume the role of protagonist in mass politics, the British empire knew its time was up, dependent as it was on a co-opted elite and a quiescent people. The subsequent establishment of democracy with universal adult franchise was thus not a benevolent concession to the masses but a recognition of their political agency.

The myth of Gandhi had already been domesticated during the Congress era, his legacy of radical political action reduced to branding welfare schemes for the ‘weaker sections’. The BJP-RSS leadership cannot even stomach that watered-down tribute as can be seen in the removal of Gandhi’s name from the MGNREGA. The sole legitimate function of the Gandhi myth is now to act as a ritual prop for foreign audiences, deployed to launder the State’s image while it imprisons civil activists under the same laws that were once used to jail Gandhi.

If the ghost of Gandhi, the icon of a liberatory mass politics, is sought to be occluded through erasure, the ghost of Nehru, the icon of a rational, progressive intelligentsia at the helm of a developmental State, is meant to be exorcised and attacked repeatedly. The narrative of ‘Macaulayvaad’ of Prime Minister Narendra Modi is its latest incarnation. Yet, against the bleakness of the present, the achievements of the early decades of Nehruvian modernism only burn a little brighter.

The large dams constructed by the Indian public sector during this period — celebrated by Nehru as the “new temples of resurgent India” — were no hubristic white elephants. They addressed multiple crises at once: expanding irrigation, generating hydroelectric power, and mitigating floods. As Ramachandra Guha recounted, the Bhakra-Nangal dam, at 680 feet the world’s second-highest at the time, requiring concrete volumes exceeding twice those of the Egyptian pyramids, generated nearly a million kilowatts of electricity and irrigated over seven million acres of land.

Nikita Khrushchev, the then leader of the Soviet Union, was taken to inspect the construction site. That Soviet delegation engaged in a technological exchange with India’s technocratic elite, aimed at strengthening the country’s heavy industrial and defence capacities. To realise these ambitions, Nehru oversaw the establishment of multiple Indian Institutes of Technology, creating a reservoir of highly-trained engineers. Yet his vision of modernity also entailed generous public support for the social sciences, culminating in the establishment of Jawaharlal Nehru University a few years after his death.

As Marina-Elena Heyink has shown, both the Congress and the communist opposition envisaged JNU as an ‘anti-colonial’ national university, one meant to move beyond the elitist and the sectarian legacies of colonial-era institutions such as the Banaras Hindu University and the Aligarh Muslim University, and chart a secular, egalitarian, and developmental path to modernity.

In 1909, the Russian theologian, Sergei Bulgakov, while diagnosing the cultural decadence in the country, observed that “Russia cannot renew itself without renewing, among other things, its intelligentsia.” Can India renew its intelligentsia? Can scientists and engineers, writers and artists, economists and scholars cohere into an autonomous social force, one capable of binding together dissenting energies across popular sectors and articulating a modernist vision for India of the twenty-first century?

Such a renewal is impossible as long as the intelligentsia remains tethered to the post-1991 neoliberal consensus and its mirage of ‘inclusive growth’ — growth for elites, scraps for the rest. As Joe Studwell commented in his outstanding book on Asian development states, India is condemned to stagnation by a market-dictated and service-led model that produces high-quality employment for only a tiny minority. “There is no way,” he wrote, “that the specialist IT firms of Bangalore or the financial elite of Mumbai will propel India to the developmental success of Japan, Korea, Taiwan, or China.” The past decade has further vindicated this judgment: Chinese firms now dominate EVs and green technologies while Indian techies have excelled mainly at shaving minutes off online grocery deliveries for the affluent.

In his 1949 essay, “Why Socialism?”, Albert Einstein argued that “science, at most, can supply the means by which to attain certain ends. But the ends themselves are conceived by personalities with lofty ethical ideals and — if these ends are not stillborn, but vital and vigorous — are adopted and carried forward by those many human beings who, half unconsciously, determine the slow evolution of society.” The decade-long assault on higher education in India is meant to foreclose any alternative vision in which equality and liberation constitute the ends of modern India. Without the conjoint development of science and the humanities as twin pillars of a renewed developmental project, Indian modernity will remain deformed: a reactionary society governed by a narrow, unaccountable elite, aided by mobs and charlatans, presiding peacefully over a politically quiescent and culturally stunted population.

Macaulay would, indeed, be proud.

Asim Ali is a political researcher and columnist