In the world of Indian classical music, some instruments arrive with thunderous fanfare, others slip quietly into history, reshaping it in the process. The esraj belongs to the latter kind. Neither ancient nor aristocratic, it was born in the middle decades of the 19th century as a hybrid — half-sitar, half-violin — and went on to embody a subtle revolution.

At first glance, the esraj seems an oddity: a long-necked wooden body strung with sympathetic wires, played with a bow instead of a plectrum. But that bow changed everything. In the late 19th century, as Hindustani music emerged from the narrow patronage of royal courts and found new audiences in colonial cities, the esraj provided a bridge between two worlds: the discipline of classical raga and the accessibility of a modern, melodic sound.

The esraj’s unlikely journey began not in Delhi or Gwalior, but in the temple town of Gaya. Here, the town’s priestly class, the Gayawals, had grown wealthy through generations of pilgrim patronage. By the turn of the 20th century, a section of them had become cultural patrons and musicians in their own right.

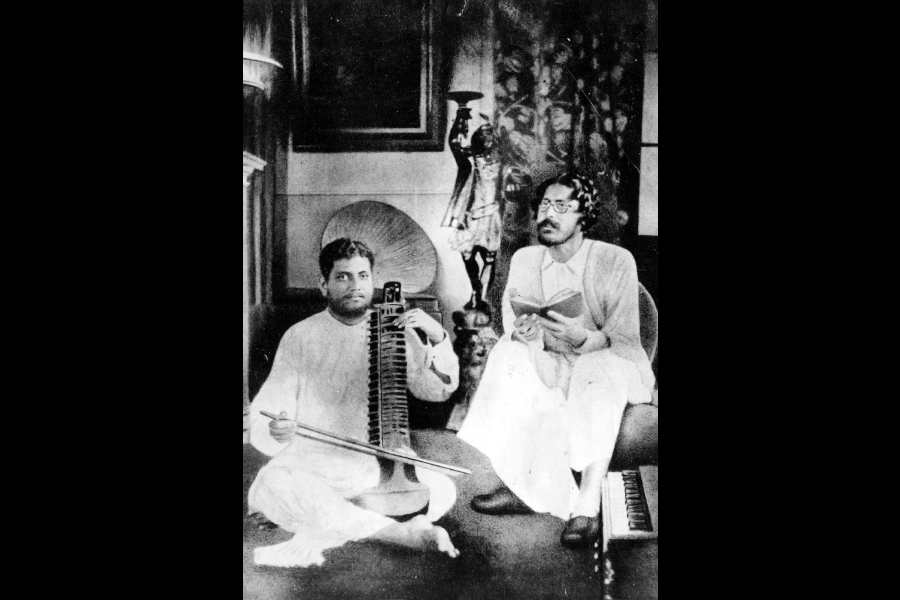

Three men, in particular, changed the fate of the instrument. Kanhaiyalal Dheri, a prosperous Gayawal priest, was among the first to perform with the esraj publicly in Calcutta’s aristocratic drawing rooms around the 1890s. His contemporary, Hanumandas Singh, refined the instrument’s tonal quality and passed his skill to a younger musician, Chandrika Prasad Dubey, of Pawai village. Dubey, often referred to as Esraj-e-Hind, achieved a cult-like status by the 1930s, touring widely and performing in estates and music conferences across northern India.

What made this group so radical was not just technical innovation but social defiance. They were not born into music; they entered it by choice. Free from the burden of lineage, they could experiment freely. They took an instrument with no ancient pedigree and made it speak with the authority of the classical tradition.

The spread of the esraj’s popularity from Gaya to the great cities is a reminder that cultural modernity in India did not flow only from courts to capitals. It also travelled along rail lines, through pilgrimage routes and small-town salons. Gaya’s Gayawals had clients in Calcutta, and as they travelled, so did their music.

In Calcutta, the esraj found an unexpected champion: Rabindranath Tagore. For Tagore, the esraj’s supple, bowed tone was a better companion for Rabindrasangeet. In the 1930s, he insisted that the esraj, not the harmonium, should accompany his songs on All India Radio. In Santiniketan, the esraj became the principal instrument for musical instruction.

The esraj became the polite sound of the modern home. It preserved the emotional range of Hindustani melody but carried none of the social baggage. In that sense, it was a democrat’s instrument, blurring the line between sacred and secular, between professional art and cultivated leisure. Yet the esraj’s story also carries a warning. Gaya’s musical efflorescence was brief. After 1950, with the abolition of zamindari and the decline of pilgrimage patronage after Partition, the Gayawals’ wealth and leisure evaporated. The esraj survived mainly in Bengal, protected by the institutional umbrella of Visva-Bharati and All India Radio, but its lineage in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh faded.

Today, the esraj has been overshadowed by the glamour of the sitar and the sarod. But its historical role deserves far greater recognition.