The world appears to be turning politically rightwards. Liberal intellectuals and mainstream media call the extreme-right-wing regimes that are coming up in some countries, and waiting in the wings in others, ‘right-wing populist’; but this description is misleading. These regimes are better described as ‘neofascist’: they resemble the fascist regimes of the 1930s, but differ in one crucial respect which justifies the prefix, ‘neo’.

These regimes have certain common features: they are repressive towards working people, radical intelligentsia and all dissenters; they foment hatred against the ‘Other’ — typically some hapless religious or ethnic minority; they combine State repression of opponents with street thuggery by their followers; their self-professed objective is setting up anti-democratic regimes; and they invert the relationship between the people and the ‘leader’ that conceptually underlies democracy by making the ‘leader’ the fountainhead of all authority. They also share two other crucial fascist traits: a close link with the monopoly bourgeoisie and an even closer link with a new stratum within this class.

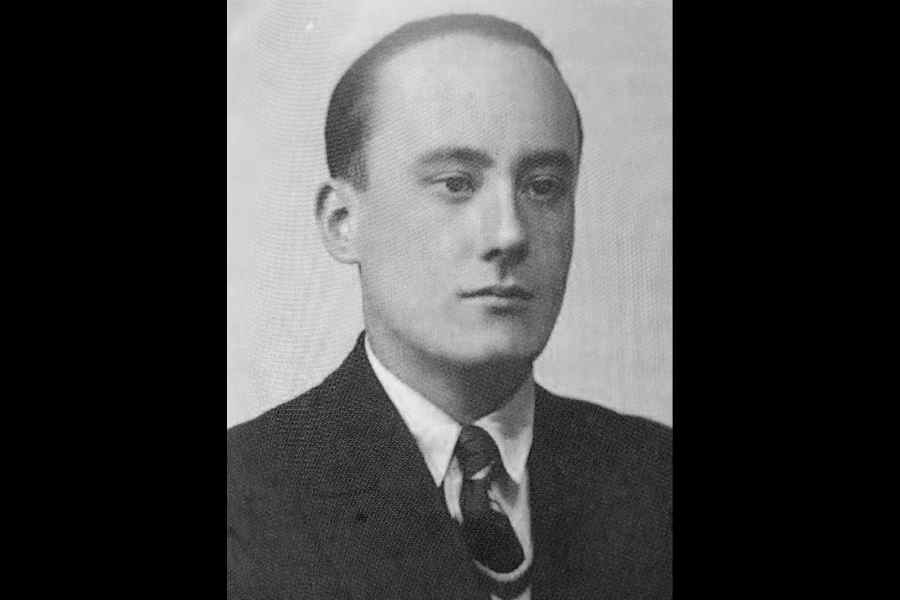

The link between monopoly capital and fascism is well-known: the economist, Michal Kalecki, had called these regimes a partnership between “big business and fascist upstarts”. Less well-known perhaps is fascism’s special link to a newly-emerging stratum of monopoly capital. The anarchist writer, Daniel Guérin, in his Fascism and Big Business had narrated how, distinct from the established big bourgeoisie in Germany located in older sectors like textiles, a new stratum of monopolists was coming up in armaments and steel with whom the Nazis were particularly close; and in Japan, the link between the military-fascist regime and the new Shinko zaibatsu, which included Nissan and was located in armaments and military-related activities, distinct from the old zaibatsu like Mitsui and Sumitomo, is well-established.

Contemporary neofascism, while solicitous towards monopoly capital in general, also enjoys close proximity with this new emerging stratum within it. India today provides a classic example of this. The term, ‘right-wing populist’, glosses over these facts and says nothing about the class nature of such regimes. Regimes so described, with the suggestion that they pit the people against the elite, actually enjoy extremely close relations with the super-elite class of monopoly capitalists.

Fascist groups exist in all modern societies, usually as fringe elements; they come centre-stage only with financial and media support of monopoly capital when it finds it necessary to have an alliance with such elements. This happens in periods of economic crisis when the regime of monopoly capital loses its old ideological prop that gave it an ethical justification; the fascists provide it with a new prop through a complete change in discourse.

The new discourse focuses on creating hatred against the ‘Other’ instead of issues like unemployment and material distress. Apart from its diversionary role during a crisis, it also seeks to divide the working people, scuttling prospects of united resistance against the hegemony of monopoly capital. The rise in unemployment during crisis also provides a fertile source of recruitment for fascist thugs. It is hardly surprising that the current neofascist upsurge is occurring in a period of crisis of neoliberal capitalism.

Walter Benjamin, the literary theorist, had said that fascism came riding on the backs of a counter-revolution. He was writing in the German context and located Hitler’s success in the string of revolutionary defeats of the German proletariat in the 1920s that weakened its resistance. Even today, the upsurge of neofascism is occurring within a context of general weakening of the working class everywhere in the world under the neoliberal order.

This weakening, illustrated by the findings of the economist, Joseph Stiglitz, that the average real wage of a male American worker in 2011-12 was no higher than in 1968 arises partly from the fact that workers are organised within nations, while capital, not just finance but even productive capital, is now globally mobile: if workers in one country go on strike demanding higher pay, capital successfully counters it by the threat that it would relocate its production to some other country.

The weakening of the bargaining strength of workers, however, is partly also a result of the privatisation of public enterprises and public services: workers in the public sector are typically more unionised and militant than in the private sector.

Because of this weakening, the share of surplus in output (the excess of labour productivity over real wage divided by labour productivity) increases within countries and in the world as a whole; and since a larger share of wage income is consumed than of surplus income, this causes an ‘overproduction crisis’ of the sort we have now. There is no solution to this crisis, through State intervention, within neoliberalism itself. State expenditure can increase aggregate demand only if it is financed in either of two ways: a fiscal deficit (which means nobody is being taxed), or taxing the capitalists and the rich (who save a part of their income); taxing workers who consume what they earn for increasing State expenditure does not raise aggregate demand. But globalised finance that dictates State policy under neoliberalism dislikes both these ways. Hence even neofascism cannot overcome the crisis, unlike in the 1930s when classical fascism had overcome the Depression through military expenditure financed by fiscal deficits. This difference from classical fascism is what justifies the prefix, ‘neo’.

Neofascism, therefore, is the progeny of neoliberalism which weakens the working class, vastly exacerbates income inequality and, eventually, precipitates a crisis that makes monopoly capital enter into an alliance with fascist elements. The opposition to neofascism is also weakened by the same weakening of the working class effected by neoliberalism.

Prabhat Patnaik is Professor Emeritus, Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi