Arsenic ingested through food and water causes silent changes in the brain that can impair the intellect and behaviour of children and young adults even in regions where groundwater arsenic levels are considered “safe”, a study in India has suggested.

Medical researchers reached the conclusion by combining for the first time brain imaging scans, intellectual tasks, and urine arsenic analysis in people below 25 years from five Indian sites.

All the study sites —which included Raniganj and Asansol in Bengal — had groundwater arsenic concentrations below the 10 microgram-per-litre safety threshold set by the World Health Organisation.

But the urinary arsenic levels appeared correlated with diet — specifically with rice, a staple that accumulates more arsenic from the ground than wheat does.

“The brain changes we’re seeing in young people can have far-reaching impacts later in life,” Vivek Benegal, professor of psychiatry at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, told The Telegraph.

Benegal is the principal investigator with the research consortium that conducted the study.

The findings, Benegal said, indicate potentially detrimental impacts of arsenic exposure on the brain, possibly from long-term ingestion through food staples such as rice, at groundwater arsenic levels “far below” the WHO cut-off.

Environmental scientists have long cautioned about high groundwater arsenic levels across the Ganga-Brahmaputra plains and other parts of South Asia, deposited there by rivers that originate near, and flow down, arsenic-rich Himalayan rocks.

Multiple studies have focused on skin lesions and cancer resulting from exposure to groundwater arsenic. Studies in Cambodia, Mexico and the US had linked impaired attention, memory and verbal reasoning to arsenic exposure.

Benegal and his colleagues studied urine arsenic concentrations and magnetic resonance imaging scans of 1,014 young people aged between 6 and 23 years from Asansol-Raniganj, Bangalore, Chandigarh, Mysore and the Rishi Valley in Andhra Pradesh.

At all the sites, they found that the participants with higher urine arsenic concentrations performed poorly in learning, memory, decision-making and risk-taking tasks, had less grey matter volume in brain regions associated with intellectual tasks, and showed more changes in their brain connectivity.

“This is the first study to show through brain scans the changes that might underlie arsenic’s effects on the brain and behaviour,” said Nilakshi Vaidya, a neuroscientist and first author of the study, published this month in the Journal of the American Medical Association Network Open.

The co-authors are from academic institutions in India, Germany, France, the UK and China.

“Our results suggest there might be no safe arsenic level at all. We need to minimise ingestion,” said Amit Chakrabarti, a physician-scientistat the Indian Council of Medical Research Centre for Ageing and Mental Health, Calcutta, and a member of the research consortium.

While Bengal has some of the highest groundwater arsenic levels in India, the study detected the highest urine arsenic concentrations among participants from Bangalore and the Rishi Valley. The researchers suspect this to be the outcome of long-term arsenic ingestion through rice.

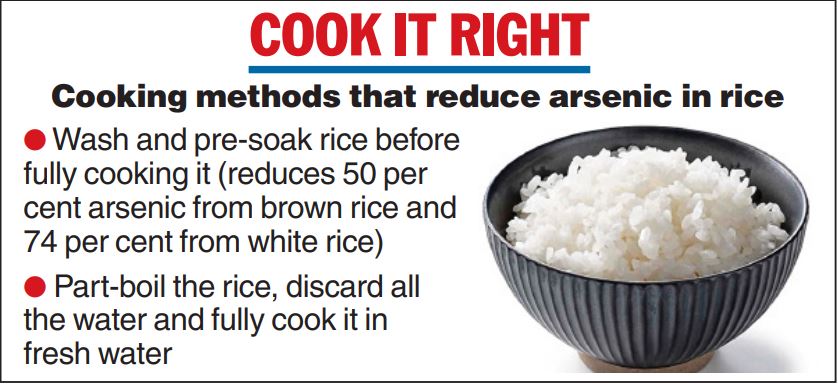

“But simple changes to the cooking methods can significantly reduce arsenic in rice,” said Chakrabarti.

“There are technologies to remove arsenic from drinking water. Such technologies need to be adopted wherever needed,” Benegal said.

The new study from India is part of a broader research effort to determine how environmental factors influence brain development, starting in the womb and through childhood and adolescent years, and show up as brain disorders or addictions later in life.

Mental health surveys in the country have indicated a rise in certain brain disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, among young people.