From one January to another, Kashmir remains one of the most thankless places in the world to be a journalist. However, up against the might of the Central government represented by the lieutenant-governor, who controls the police in Jammu and Kashmir, and intimidated by it in Delhi, where major newspapers are headquartered, both Kashmir’s elected chief minister and India’s mainstream press have fallen short of standing up or speaking up.

In January last year, while quashing the latest preventive detention order targeting journalists, the Jammu and Kashmir High Court described it as “malice-inducing and unlawful”. The owner of two newspapers in Jammu, Tarun Behl, was arrested in three criminal cases and served one preventive detention order in two months. The preventive detention order under the Public Safety Act was passed on the same day that he was granted bail in the third case in September 2024. The judge said that the sequence of events showed that the petitioner “was somehow being eyed upon to be a witch-hunt by the authorities”.

And this month, there has been a flurry of excited commentary after an Indian Express journalist in Srinagar, Bashaarat Masood, was summoned to a cyber police station for his reporting and asked to sign a bond in Urdu which said that he would not do anything that would disturb peace. The paper had published a story by him on January 13, billed as an exclusive, which said that in Kashmir police were seeking granular information on mosques and those who run them. It was described as a large-scale exercise to collect information on mosques and their imams, muezzins, the members of their management committees and their charity wings.

He was summoned to the police station the day after publication and three times thereafter, during which period the paper published a follow-up on January 16. Masood told the magistrate he did not know the reason for which he was being asked to sign the bond, following which the police took him back to the station. His last visit was January 19. His paper in Delhi reported it on January 21, saying that Masood had not signed the bond as asked by the police, and that The Indian Express was “committed to doing what is necessary to uphold and protect the rights and dignity of its journalists”.

Before The Indian Express’ statement was published, the story had been flagged on X and picked up and published by The Wire. In the interim, the police summoned a journalist of The Hindustan Times as well. The paper criticised the move in an editorial on January 22. The Hindu’s correspondent in Kashmir was apparently also summoned by the police, but was not in town. One does not know whether these newspapers will mount a further pushback against the government.

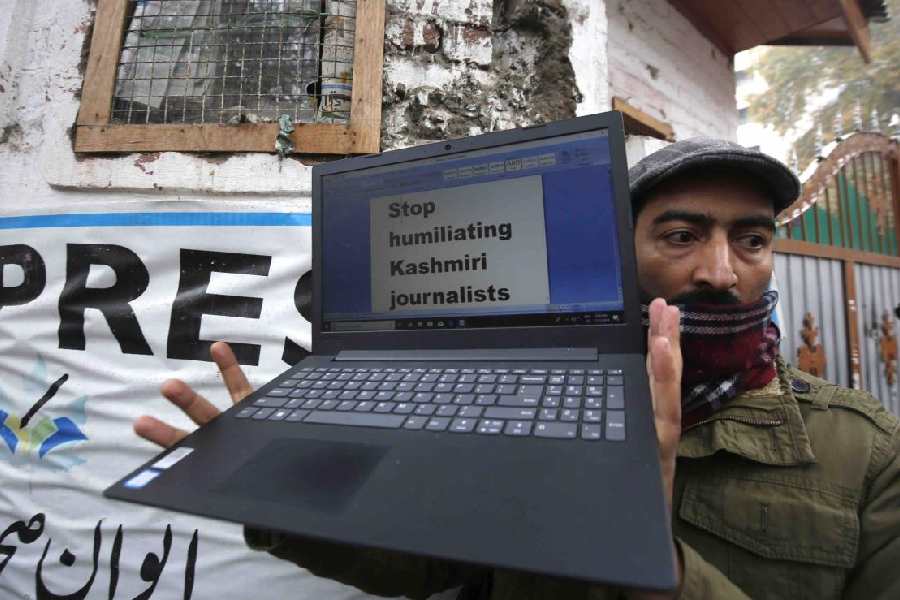

The greater the pressure on journalists, the more incumbent it becomes on media owners to back them to fight back. Instead, we are witnessing a countrywide media capitulation to bullying. A news item on page 16 in a mainstream paper reporting that the Press Club of India slams J&K police over oral summons to journalists, is not an adequate response. Critics suggest that The Indian Express took its time to report on the repeated summons to its reporter. Kashmir’s frequently harassed freelance reporters are both incredulous and disappointed.

The chief minister, Omar Abdullah, though, has been the really big letdown. Statehood has brought no meaningful restoration of media autonomy since he came to power in 2024. While several political leaders and religious figures have condemned the summoning of Kashmiri journalists to police stations and forcing them to sign bonds and affidavits for reporting on the profiling of mosques and imams in Jammu and Kashmir and expressed outrage, the ruling party, National Conference, continues to maintain silence. Omar Abdullah has not said a word, nor has the party issued a formal statement condemning the summoning of journalists.

Right through the year, 2025, there was no let-up in what journalists and media owners were up against, with Operation Sindoor making matters worse for several months. It placed severe restrictions on media reportage, and most Kashmiri journalists were not able to report developments on the ground. Their use of social media also drew attention, with a senior journalist, Hilal Mir, who worked for an international agency being hauled up by the Counter Intelligence Kashmir wing of J&K Police for a Facebook post on May 1. He was described as a “radical social media user” given to disseminating “extremist/distorted content”.

Over the rest of last year, media accreditations of prominent national publications were revoked, and journalists have been denied press passes even to cover the legislative assembly proceedings. The office of the Kashmir Times was raided, though it is now published from the United States of America, and the 2022 book of its managing editor, Anuradha Bhasin, was banned in August. Almost 25 journalists were summoned and harassed in the course of the year, Newslaundry reported. The Public Safety Act, under which journalists can be hauled up, continues to be in force.

The crowning touch came in October-November with a verification process being initiated. A Department of Information and Public Relations order issued on October 31 to district information officers of the Kashmir division sought to alert them to the “misuse of media identity” and “unverified individuals misusing the name of journalism”. Individuals on social media using journalism as a cover for blackmail and extortion is apparently a phenomenon here and could be one reason for this move, but the order is broad enough to deny access to bona fide freelance journalists in a district. The verification process demanded detailed personal and professional information, including submission of salary slips. For freelance journalists, the process has become an ordeal involving being summoned to the local police station, having their mobile phones confiscated and being made to sit there for hours.

The government’s justification for such a directive is the “repeated complaints” received about the misuse of media credentials, and the need to curb impersonation, blackmail, extortion and circulation of defamatory content. Officials argue that the move was necessitated by the rise of social media platforms that have blurred the lines between professionals and self-styled journalists. Some operators have been arrested. A journalist in Srinagar called them mic warriors, a tribe that can apparently procure cheap mics on hire. They extort by demanding large sums in exchange for deleting fabricated and defamatory videos uploaded on social media. Their rise has only added to the many challenges of trying to practise journalism in Kashmir.

Sevanti Ninan is a media commentator. She also publishes the labour newsletter, Worker Web.