With AN UNTIMELY CALENDAR By Raqs Media Collective, National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, price not mentioned

I had half a day in Delhi, last month, to see Untimely Calendar, the exhibition by Raqs Media Collective now on at the National Gallery of Modern Art. Delhi was preparing for the advent of the American president for Republic Day celebrations, and everything, especially the traffic, was in a state of oddly quiet wintry chaos around Jaipur House. Military tanks in Christo-like wrappings were parked close by. I entered the museum and realized within minutes, in a state of mounting distress, that the splendid transformation of space - museum-space and mind-space - that Raqs have made in this show, surely one of the most epochal in the history of contemporary art and thought, demanded a kind of time that I could not see myself being able to make in my everyday life at that moment. It was with this feeling of restlessness and rue - a kind of alarm that I would miss something important because of a lack of time - that I began to understand the alluringly disruptive power of the show's eponymous 'untimeliness', and the possibilities of transformation, not just of space, it gestures at. The journeys of the body, mind, memory and imagination opening up inside the familiar architecture of the museum, defamiliarized as if in a dream, were asking me, brilliantly and seductively, to re-arrange time inside my body and head, and in my own calendar, in order to make room for the exhibition.

It is a show full of huge, mythic, usually slow and potentially lethal animals - elephants, whales, rhinoceroses. They not only bring to it their fleshly unwieldiness but also become figures of a conceptual abundance, or generosity of sentience, that forces us to re-adjust the scale and register of what we allow ourselves to engage with in our unexamined lives. 'An artistic action,' write Raqs in a meditation on art, agency and politics, 'is the means by which humanity adjusts the infinity of being to itself.' They then quote from Tagore's Religion of Man, to talk about 'the angel of surplus', who, like these oversized creatures, compels us to break the bonds of tidiness and finitude, and create open, but disquieting, spaces in which 'Man's thoughts and dreams could have their own holidays'.

Confronted with the potential unmanageability of human reason and unreason that constitutes the shared creative process of this collective of three artists (Monica Narula, Shuddhabrata Sengupta and Jeebesh Bagchi, who are also writers, teachers, travellers and conversationists, working together since 1992, after being in university together), I was about to give up on being able to absorb the entire experience of the show in my limited time, when I got the book that accompanies the exhibition. And bringing the book back with me to Calcutta - a city that appears, together with Bengal, at key moments in the book and the show - I had the even more curious experience of trying to fit my memory of the show with the corresponding, yet independent, spaces and possibilities that open up in the book. Seeing the exhibition was like walking around inside a beautifully difficult book, and reading the book was like walking around inside a beautifully difficult exhibition. Yet, the book realized by the show was not the book I was reading here, and the show conjured up by that book was not the show I saw in Delhi. And the gap, the lack of an easy and indexical fit between show and book, becomes one of those deliciously challenging 'rifts' through which the reader/viewer is invited by Raqs and their various collaborators to 'dive into the thick of things'.

One of these collaborators is the book's editor, Shveta Sarda, who read through the Raqs archive of 'essays, interviews, letters, proposals, e-mail exchanges, notes, works, drafts and lecture performances by Raqs, some published, others not' in order to 'sculpt a figure of kinetic contemplation' through 100 deceptively spare and minimally laid out entries, and a full - sometimes overwhelmingly articulate - descriptive index of texts, images and installations in the book and the show. Somewhere between field-guide, journal and commonplace book, With an Untimely Calendar brings out two remarkable characteristics of the work done by Raqs so far.

First, they radically unsettle our notion of the creative process as emanating from the unitary self of an individual artist. They disperse it, instead, into a layered web of many different modes of intending and evolving and bringing into being, which have to do with connectedness and solidarity, on the one hand, and multitudinousness and collectivity, on the other. In this, the factory or industrial site, with its log-keeping 'time book' for the workers, becomes as vital, and vitally politicized, a place of labouring as the artists' studio or the World Wide Web. Second, the ultimate sensory experience offered by Raqs, and necessarily so in the book, is a banquet of words - a profound and often unabashedly flamboyant savouring of the powers, and limits, of language as it transforms, translates, transmutes, transgresses and transfigures the boundaries of body, mind, money, history, space and time into its own, continually changing, forms of work and play.

For those who have not seen the show, the book works as an anthology of writing, presented in the form of Nietzschean meditations or Borgesian fragments that elude the categories of theory, philosophy, poetry, fiction, conversation or correspondence. Even when describing artefacts, the writings delight enough in their endless wagers of thinking, telling and asking questions, in the copiousness of language itself and in the plenitude of life, to be valuable in themselves as a means for the 'dilation and intensification of awareness'. This dilation is a slowing down of time that demands a particular kind of patience with the little movements of history, beautifully embodied in the video loop of a photograph taken in Calcutta in 1911, An Afternoon Unregistered on the Richter Scale: 'How do we know whether things are changing quickly, or slowly, or not at all? What kind of patience does a historian require to be able to slow things down in his or her mind, so that some change is visible, or what kind of energy does it take to speed up the tempo of observation such that things can be observed to be in flux, while and before they completely change?'

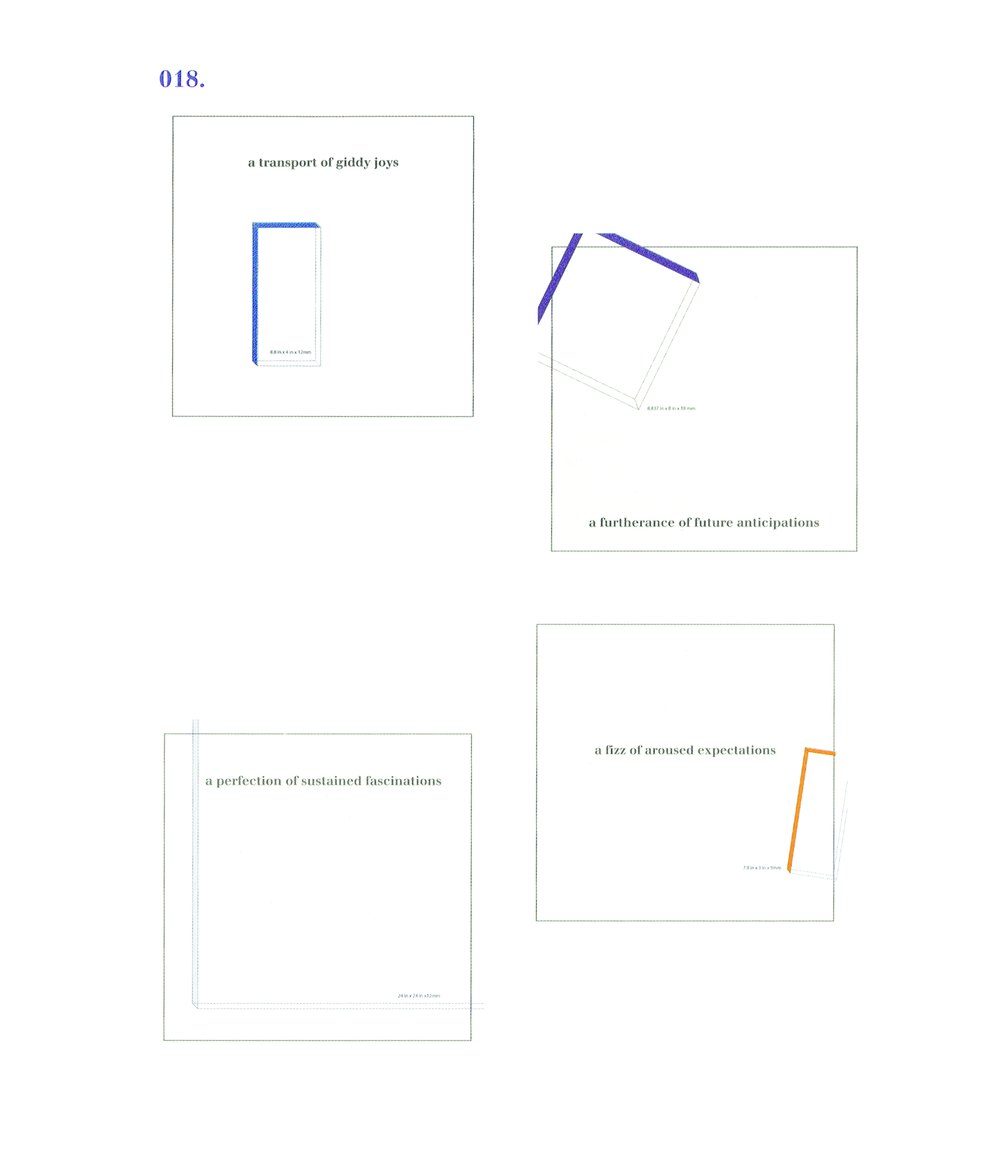

On the left, above, is a portion of what is printed on canvas and draped on a steel table with a wooden top, on which is placed a metre-long steel measure. This installation is called One Meter of Truth (Emotion) in the show. Its verbal evocations of complex states of body and mind, which are impossible to measure and classify, were composed by Raqs while working with theatre artists on Abhinavagupta's manual for poets and performers on the rhetoric of emotions. On the right is the Untold Intimacy of Digits - the animation of an 'archival trace' shown as a video loop. If a 'trace' is 'an image of an event-shaped hole', then the event haunting this work is the dispatching, in 1858, of the handprint of a Raj Konai, who lived in Bengal's Jangipur, to the eugenicist, Sir Francis Galton, by William Herschel, a scientist, statistician and revenue official with the Bengal government. Raqs found this print in a London archive, where it got them thinking of 'how bodies can be made to utter truths that minds need not deliver'.