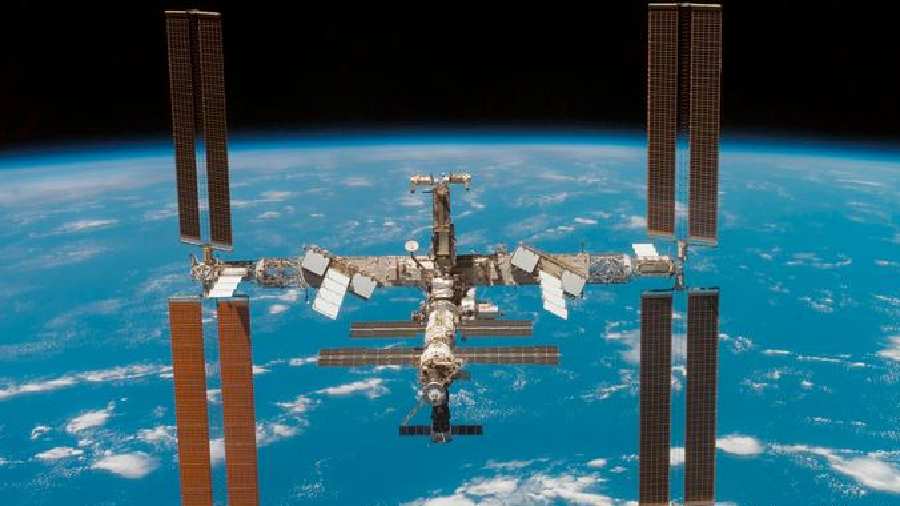

For more than two decades, the International Space Station has served a crucial diplomatic role as an outpost of cooperation between the United States of America and Russia, even amid broader tensions between the nations. That might now change, with Russia declaring its intent of withdrawing from the project after 2024 amid the war in Ukraine that has divided the world. Moscow has said that it wants to focus its resources on building its own space facility: apart from the US and Russia, the ISS also has Japan, Europe and Canada as members. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration of the US responded by suggesting that Moscow’s pullout would not impact the space station. The ISS was expected to function until 2030; so it is understandable for key space-faring nations to plan for a future after that. But Russia’s decision and Nasa’s reaction point to a direction that is far from ideal. In the short term, the US will need to find an alternative to the Russian propulsion systems that keep the ISS oriented correctly. There is also a more basic concern: the Russian side of the ISS hosts one of only two toilets on the giant satellite. What will happen to it is unclear.

But in the long run, an orbital rupture could have more serious consequences. The militarisation of outer space has been a threat since the Cold War. The Outer Space Treaty, adopted by the United Nations in 1967, forbids the deployment of weapons of mass destruction in space. Over decades, a consensus had developed that space must be treated as a part of the global commons (like oceans). That understanding has been under threat in recent years, with the US declaring a Space Force and unilaterally allowing its companies to mine the moon under its former president, Donald Trump. In 2020, the US accused a Russian satellite of tailing its spy spacecraft. China has described space as a “critical domain of international strategic competition”. Russia’s withdrawal from the ISS will mark the latest setback to efforts aimed at keeping outer space a theatre of cooperation rather than contestation. As the history of colonialism shows, a race towards the exploitation of new frontiers inevitably leads to the military defence of those investments. What the world needs is more projects like the ISS, not less. Outer space must continue to inspire wonder and dreams — not weapons and destruction — for future generations.