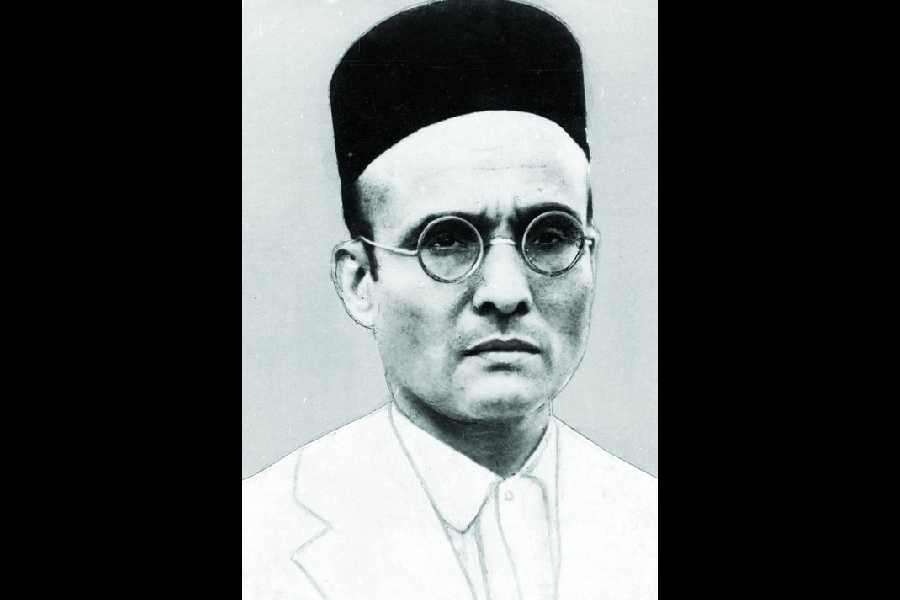

In the intellectual marketplace of contemporary India, there is an ongoing effort to rehabilitate Vinayak Damodar Savarkar as a ‘political theorist’ of substance rather than as the ideological architect of division. Much of this recent scholarship hides behind theoretical jargon, invoking ‘historicism’ and even Leo Strauss to justify re-readings of Savarkar’s thought. Beneath the academic scaffolding lies a dangerous impulse — not to understand Savarkar but to refashion his image as a philosopher of nationalism.

The claim that India’s political theory remains ‘underdeveloped’ because of historicist tendencies is intellectually dishonest. The so-called ‘poverty’ of Indian political thought arises from the refusal of a plural society to be captured by the singular logic of Western abstraction. India’s thinkers were not deficient in theory; they simply refused to divorce moral life from political life. The real deformity of modern Indian political imagination emerges from the likes of Savarkar whose reduction of politics to identity, and community to creed, has done more to impoverish moral inquiry than any historicist method ever could.

To accuse ‘historicist scholarship’ of diminishing Savarkar’s originality is to misunderstand what that scholarship reveals. When historians situate Savarkar in his time, they are not flattening his thought — they are exposing its ideological roots, its moral bankruptcy, and its consequences. Scholars who pretend that Savarkar’s ideas can be salvaged by detaching them from their historical and ethical implications risk participating in the very falsification that contemporary power structures thrive upon.

The invocation of Strauss’s “hermeneutics of esotericism” to justify a ‘trans-historical’ reading of Savarkar is perhaps the most egregious intellectual distortion. Strauss proposed reading hidden meanings in texts to uncover subtle philosophical intent. But Savarkar’s texts are not coded — they are explicit. His calls for Hindu unity through

violence, his justifications of cruelty, his disdain for Muslims, Christians, and even pacifist Buddhists are loud proclamations. To apply Strauss’s method here is not interpretation, it is whitewash.

Equally absurd is the attempt to draw analogies between Savarkar and Carl Schmitt. Schmitt remains an intellectual figure debated for his conceptual rigour on sovereignty and legality. His work interrogates the limits of liberal constitutionalism; it does not sanctify racial supremacy. Savarkar’s thought, on the other hand, is soaked in majoritarian resentment. His Essentials of Hindutva constructs a political identity that exists only by excluding others. His nationalism is not built on civic solidarity or shared destiny, but on perpetual enmity.

The effort to rationalise Savarkar’s contempt for Buddhism and his derision of pacifism as ‘political realism’ is another act of distortion masquerading as analysis. Savarkar’s rejection of nonviolence is not a philosophical critique of moral idealism; it is an erasure of India’s pluralist ethos. Equally hollow is the lament that Savarkar has been ‘marginalised’ by historicist bias or ideological discomfort. He has been marginalised not by bias but by truth. The academic discomfort surrounding him arises not from fear, but from moral clarity, a clarity that recognises in his writings a blueprint for division.

What these revisionist projects ultimately attempt is not reinterpretation but redemption. They seek to restore to Savarkar philosophical respectability by divorcing him from the real-world consequences of his ideas — the poison they injected into India’s public life, the ideological scaffolding they provided for the politics of hate. To dress this legacy in the robes of theory is to turn history into theatre and scholarship into servitude.

Irfan Gull is a Provisional Executive Member, Jammu & Kashmir Youth National Conference