Book: CALLED BY THE HILLS: A HOME IN THE HIMALAYAS

Author: Anuradha Roy

Published by: John Murray

Price: Rs 999

Reading Leela Majumdar permanently shifts one’s perception of the mountains. For Majumdar, the mountains are as forbidding as they are homely, a place that not everyone can learn to live with given the weather’s sovereignty and the ground’s stubbornness. Majumdar’s prescription to survive the mountains is thus to assimilate the way people carry knowledge in their bodies and speech and recognise the humour that survives even in harsh conditions. The memory of Majumdar’s writing makes its presence felt in Anuradha Roy’s Called by the Hills, even before she is mentioned by the author. This is a book of dwelling in and with the mountains: patient, alert, amused, and increasingly uneasy about what is happening to the land that Roy clearly falls in love with.

Roy has written about Ranikhet before, perhaps most memorably in The Folded Earth, where the town becomes both refuge and reckoning, where the monsoon tests endurance but grief and solitude also find a landscape large enough to hold them. Called by the Hills carries those textures into non-fiction. While Roy’s fiction had the freedom to arrange experiences into a pattern, her memoir works through the slow authority of a lived reality. The result is a book that behaves like mountain time: looping, seasonal, digressive, attentive to the ordinary until the ordinary becomes revelatory. The book’s structure resists linearity and, instead, moves by association, anecdote, seasonal rhythm, and memory. That meandering suggests that inhabiting is not a completed act but a continual negotiation, a way of living that remains provisional even after decades. The text makes space for contradiction: love for a place alongside fear, intimacy alongside estrangement, beauty alongside grief for ecological degradation. In this, Roy’s memoir aligns with a tradition of writing about home as a site of ongoing formation rather than possession.

The book also carries within it a whole library. Garden writing, Himalayan scholarship, travel accounts, natural history, environmental thought, literary reflections on craft and form: such literary references appear throughout, like faint marks of older handwriting under fresh ink. Called by the Hills is thus a palimpsest in the most natural way where reading is used both as a scaffolding and a running conversation with those who have looked at, lived in, and written about mountains before. A line from an older text becomes a hinge for Roy’s own observation; a remembered passage becomes a lens through which a familiar place looks new.

Gardening is the book’s central practice, and it quickly turns into something more than aesthetic pleasure. Roy’s garden is a site of learning and failure, of patience forced upon the impatient, of effort meeting resistance. It also becomes a record of environmental history. Digging reveals layers of plastic and glass, refuse compacted into the hillside, making cultivation feel like excavation. The garden holds the tension between care and damage: human effort can heal a patch of land, and human habits can also sterilise it. Roy’s writing stays honest about her own contradictions. She brings in foreign seeds, aware of the ecological risks, seduced by rarity and beauty, and she admits that emotion often wins its argument with science. That admission matters because it keeps the book from drifting into virtue.

The animal life in Roy’s Ranikhet is equally pragmatic. Dogs arrive and become family; birds and monkeys turn the garden into a theatre of appetite and mischief; leopards remain a real presence, shaping movement and fear. When loss comes, it shifts the emotional architecture of the household and the moral texture of the forest. Roy does not dramatise this for effect. She lets it register as a change in relationship, the kind that alters how one walks, listens, and trusts.

Roy’s social world is drawn with the same sharpness. The housekeeper, whom she calls the Ancient, is one of the book’s most vivid presences, and she functions as more than a colourful character. She is a keeper of norms, an interpreter of class and gender, a living reminder that belonging is negotiated through daily behaviour. Through her, Roy shows the quiet governance of domestic life in the mountains: what a proper garden should look like, how a memsahib ought to behave, who gets to be eccentric and who gets disciplined into being sensible. The humour here is dry, often affectionate, and always edged with reality.

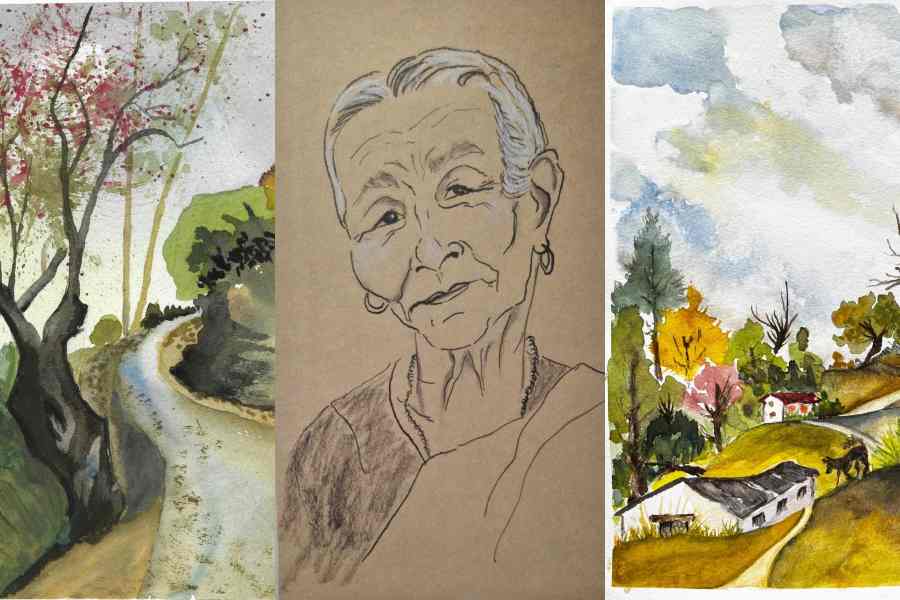

Roy’s watercolours (pictures) are not decorative add-ons but another mode of paying attention, a second register of seeing. They slow the reader into the pace the prose insists upon, where the colour of a barbet or the shape of a hillside becomes worth noticing for its own sake. They also complicate the book’s beauty. The images charm, while the text keeps returning to damage, precarity, and the limits of individual care.

Roy treats the hills with seriousness, not as a flattering backdrop for a city person’s reinvention. Her Ranikhet is a working community, rich in local intelligence, and a landscape that yields itself only to those willing to submit to time, effort, and consequence. In the end, Called by the Hills becomes a study of attention as a form of moral practice: it clarifies what close looking can teach as well as what close looking cannot undo. That clear-eyed restraint is where the book finds its quiet authority, and its undertow of sadness.