|

|

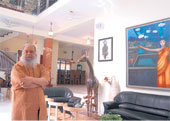

| LIVE LIFE KINGSIZE: Artist Suvaprasanna in his plush home (top) and (below) Mumbai-based artist Jehangir Jani relaxes with his dogs in his drawing room |

Once upon a time art and struggle went hand in hand. In Europe, Vincent Van Gogh, the Impressionist, died in poverty. Closer home, look at veteran artist Paritosh Sen. He recalls his first solo exhibition in Mumbai in 1948. The show managed to sell just one of his paintings for Rs 100. “I had spent Rs 500 to go to Mumbai and I was expecting that the sales money would help me get back. I was wrong and got stuck in the city for a week. I was on bread and water, literally, for seven long days.” Finally a friend bailed him out.

Other examples abound. People at Santiniketan still remember how the sculptor, Ramkinkar Baij, pursued art amidst grinding poverty. He worked with bamboo sticks when he couldn’t afford iron rods and used raw cement instead of plaster because plaster was too expensive for him. Says Kakali Ray, a former student of Sangeet Bhavan in Santiniketan: “In 1967, when I was a fresher, one of the seniors came up to me and asked me, ‘Do you know that man?’ I spotted a man in dirty blue trousers rolled up to his knees, a ragged shirt and a toka on his head. With little hesitation, I replied, maybe the kitchen server. The senior smiled and said, ‘He’s the famous Ramkinkar Baij.’”

In the beginning of his career, artist Ganesh Pyne stayed in a dilapidated house on Central Avenue. “The house was in such a state that we used to be scared of climbing the stairs,” recalls a friend. “Pyne’s studio was a cramped room in that building. Poverty was such a reality for him that he could not even afford an easel or a fancy canvas.” Pyne himself says: “When we started painting there was no art market. The idea of eternal struggle and poverty was a part of our lives.”

But the art landscape has changed — and how! Today struggle is out — and money is in. Pyne’s works, for instance, now fetch $300,000 at auctions. Materialistic and confident, the artists are the new maharajas of the Indian art world. And, like royalty, they are no longer afraid or ashamed of flaunting their money.

“Why should we be,” asks Suvaprasanna, who owns a cottage at a luxury resort at Raichak on the banks of the Hooghly. “If I were a businessman, no one would have raised eyebrows at the fact that I own a cottage in a special place. Why does my profession as an artist make me vulnerable to such unwarranted queries?”

Life for successful artists these days is like camphor essence — fleeting, but beautiful while it lasts. Raghava K.K. realised that early in life and took up painting because he wanted to “enjoy the finer things of life.” The 26-year-old should be happy: his company, Raw Umber India, which manages his career, had a turnover of $1 million last year.

Mumbai-based artist Jehangir Jani believes it’s time people stopped stereotyping artists. He invests in mutual funds and has a penchant for Dolce & Gabbana designer clothes. And he likes to travel to the US, Europe, Africa, Russia and New Zealand.

“Artists are not only the new maharajas today, but they have flying carpets,” says Ina Puri, a Delhi-based art consultant. “There is this sudden flurry of building new studios and buying new cars. Artists today are no less than Page 3 personalities.”

The evidence that some artists are making money hand over first is compelling. While in 2003, $4.5 million worth of Indian art got auctioned, in 2006 the figure escalated to $170 million. In September 2006, Sotheby’s and Christie’s saw their Asian art sales take off, fuelled by the strength of modern and contemporary art. Indian art valued at a total of $45.35 million and $34.99 million, respectively, was sold.

According to Calcutta’s Aakriti Art Gallery, the returns on art investments in 2006 were 104.8 per cent as against 48.7 per cent on gold investments. “The art scenario in India is buoyant,” proprietor Vikram Bachhawat exclaims, pointing out that in recent times, the works of Atul Dodiya, Jogen Chowdhury and Surendran Nair touched the Rs 1 crore mark, while those of Tyeb Mehta, F.N. Souza and S.H. Raza crossed it with Rs 5.5 crore, Rs 5 crore and Rs 4 crore, respectively.

Reflecting the new interest in art, there are popular portals devoted solely to Indian art. Ravi Kumar Kashi, who has his shows scheduled in California and London in the next four months, points out that London has six galleries exclusively for Indian art. “Visibility has become easier,” says the Bangalore-based artist.

So it’s easy to understand why Atul Dodiya dreams of buying a villa in Florence. The Mumbai-based artist, who has a large collection of books, plans to expand his studio and is not greatly bothered about how much it’s going to cost him. “And I’d love to travel across the world, especially to places such as Turkey, Egypt and Greece,” he says.

There are some, however, who are still a little iffy about what the advent of money means to the world of art. Delhi-based art collector Siddharth Paul is disgusted with what he calls the buy-and-brag trend. “I can’t associate money with a true artist,” he says. “For me, art comes from pain and passion. Money blunts a painter’s instincts.”

But Piyush Lala, a 28-year-old freelance commercial artist in Mumbai, has no patience with those who club art with want. “People should stop associating artists with a jhola,” stresses Rajasthani artist Chintan Upadhyay, who has invested money in a joint venture as a producer of the film Kya Tum Ho which had its world premiere two months ago.

People like Delhi-based veteran artist Satish Gujral stress that material success does not necessarily corrupt art. On the contrary, it may even help artists strengthen their creative independence. “But the lifestyle of an artist has no relevance in judging his work,” he adds.

Senior artist Jogen Chowdhury, whose works commanded a price of $370,000 plus in 2006, defends the art fraternity. “So what if artists are going for posh flats, cars and investments? Think of Picasso and the huge castles he lived in. Today, the whole world is going through a transition period. There’s some sort of exaggeration in every sphere of our lives. Artists are no exception.”

Money, Chowdhury stresses, may even have given artists more confidence. Though Chowdhury still drives an old Fiat Uno, he has no issues “if other artists are spending money with alacrity.”

Elsewhere, however, Unos have given way to snazzier cars. After all, it is not easy to drive a battered car to an art exhibition held in a 5-star hotel. The opening of an exhibition is a much touted affair. Steaming cuppas and samosas, which were typical snacks at exhibition inaugurations till the other day, have been taken over by wine and canapes.

Delhi, Mumbai and Bangalore are no longer the coveted spots for art camps. Instead, the favourite locales are Myanmar, Thailand, Indonesia, and the US. Says 1983 National Award winner Yusuf Arakkal: “Earlier, I attended art camps where we slept in dormitories and travelled to and fro by train.” In the last camp in Istanbul, Arakkal travelled business class to Turkey and was put up in a 5-star hotel.

Organisers of such camps claim that several artists actually charge not less than Rs 1 lakh as honourarium to participate in an art camp, apart from ensuring that they are put up in 5-star hotels and taken around on city tours in air-conditioned buses. “Some are even beginning to demand business class flight fares along with money for their personal shopping expenses. “Frankly, I find this new aggressive stance laced with a streak of greed a little shameless,” says an organiser who’s been associated with the art world for the last 18 years.

Adds investment consultant Vikas Srivastav: “Land acquisition, real estate investments or foreign bank accounts have never been so much an artist’s choice. But now the artist not only wants to achieve in concrete terms but also wants to show off his acquisitions.”

Says Pratiti Basu Sarkar, chief administrator of CIMA Art Gallery, Calcutta, “Artists have become aware of money — and I don’t think this is necessarily a ‘bad’ development. It is probably a self–preservation instinct for the artist because the past was so difficult.” However, she feels that perhaps artists should focus on their creativity while professionals manage their money. “Preferably, the artist should reflect and express creatively, and leave money management to their accountants or, as is done abroad, to the galleries representing them.”

Additional reporting by Varuna Verma in Bangalore