|

|

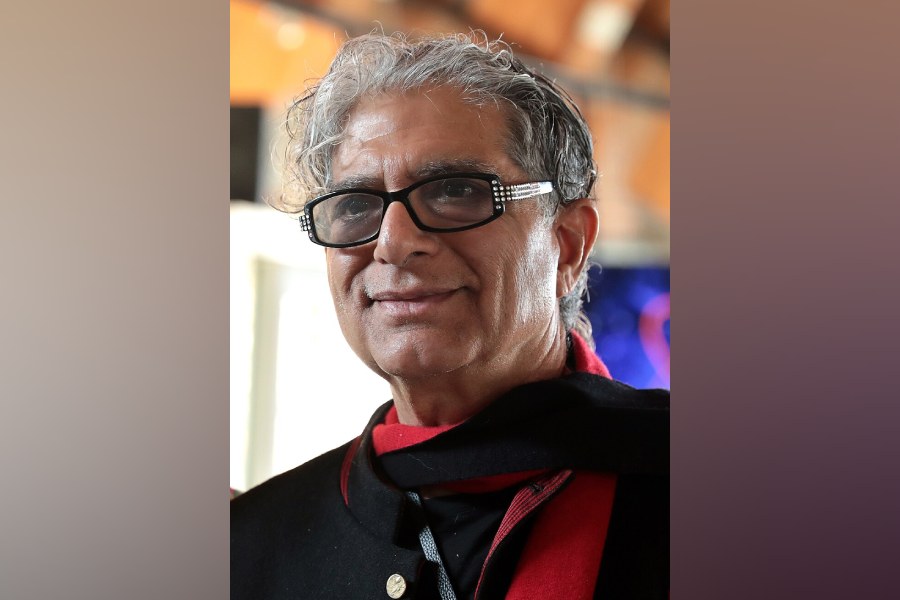

| (Top) ‘Portrait of a marriage 77’ and ‘Portrait of a marriage 91’ from House of Love |

What is Truth? said jesting Pilate, and would not stay for an answer. What is truth, asks Dayanita Singh with her latest book of photographs, and will not leave till she has an answer.

With House of Love, published by Peabody Museum Press/Radius Books and launched on November 27 at Oxford Bookstore, she tries to hold her viewer, make him stay on, seduce him into the photograph, to make him figure out what is within. Rather, what is not. She is asking him to find out what the darkness engulfing the pictures contains within it. What it stretches into. She is a bit like the Ancient Mariner, too, and a little more demanding — she will not let him pass, but will not tell the story either. She will ask him to imagine it.

She gives him clues. The photographs are the clues — Taj Mahal, the original house of love, other houses, people, cityscapes, forlorn, glowing strangely against an unnatural night sky. But the photograph is fiction already — the men and women, the places, are touched with the surreal, the unreal. The photographs are tricks.

The photographer has deliberately used the wrong film — daylight film in night, for that unnatural colour. Deceit. Can we depend on such clues to venture into the darkness outside?

But the journey must be made, insisted Singh. “What is left out is most important,” she said, counting Michael Ondaatje, “the master of gaps”, as one of the influences on the book. She called her art “photofiction”. She wanted her photography to aspire to the condition of literature.

House of Love is like fiction in a simpler way, in its form. The photographs often flow in a sequence and tell a story, challenging the idea of a photograph as a single thing.

Aveek Sen’s prose accompanies the photographs, following its own rhythm. Sen agreed with Singh that “what is happening is outside the frame”.

“Photography is not the truth,” he said. He read one of his essays, a sparkling little piece that talked about Troilus and Cressida, love and illusion, treachery and deceitfulness. Things, including photographs, are not what they seem.

Professor Supriya Chaudhuri, who teaches English at Jadavpur University, was in conversation with the artist and the writer. She pointed out the burden of truthfulness that photography has to bear. Critics such as Walter Benjamin and Roland Barthes have spoken about the truth-telling function of photography. But art such as this liberates photography from its duty.

So where is the love in the House of Love? What lies in the darkness around? What is troubling your mind? Try and find out. Dayanita Singh demands nothing less than the viewer’s love.

Affair of the heart

It was an unusual book launch where the guests talked about the “owls of society” (the moral police who frown at even the most “natural emotions”). They also warned that this book contained “explosive” material that may invite litigation. But then it was an unusual book, one that involved Tagore and his son Rathindranath, the first vice-chancellor of Visva-Bharati.

‘Apni Tumi Roile Dure — Shongo Nisshongota o Rathindranath’ by Nilanjan Bandyopadhyay, brought out by Dey’s Publishing, was launched on November 26 at the Oxford Bookstore by Saugata Roy, Union minister for state urban development. Present were film-maker Aparna Sen, artist Suvaprasanna, former vice-chancellor of Visva-Bharati Rajat Kanta Ray and film-maker Jayabrato Chatterjee.

The book has an essay on Rathindranath (1888-1961) by Nilanjan Bandyopadhyay, a special officer at Rabindra Bhavana, Visva-Bharati University and member of the West Bengal Heritage Commission. The essay not only highlights Rathindranath’s immense contribution to Tagore’s Santiniketan but also mentions how he was almost hounded out of Santiniketan after his father’s death.

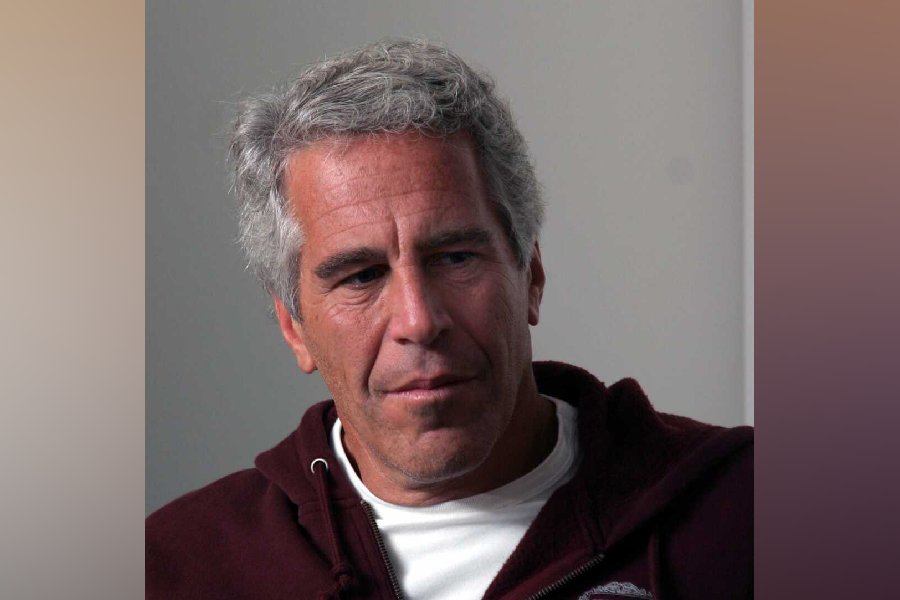

|

| Rathindranath Tagore and Mira Chattopadhyay |

Enclosed within its covers are letters from Rathindranath to and from a host of people including Nirmal Chandra Chattopadhyay and his wife Mira, his closest friends in his last years. At 65, Rathindranath resigned from his post as vice-chancellor and left his wife Pratima, adopted daughter Nandita and his home in Santiniketan to live with Mira (then in her 30s) and her two-and-a-half year-old son Jayabrato in Dehradun. It was here that Rathindranath built Mitali, a house that replicated his home in Santiniketan. They lived together for nine years till his death, with Nirmal Chandra often visiting them with his daughter.

Rathindranath tried to build something like Santiniketan in Dehradun. At his impetus, Rabindrasangsad held Tagore-related programmes.

In a letter to friend and one-time colleague Leonard Elmhirst, Rathindranath wrote: “I am not an escapist. I am going into seclusion because I want to discover myself and give opportunity to any latent impulse that might be waiting development”. More privately, he admitted to Nirmal a desire to break free of all the lies and tangle of ties in which he was ensnared. Rathindranath wanted to “disappear” and be “forgotten”. He wrote to Meera that all he wanted was to spend his remaining days in peace and she, “Meeru”, was all that mattered to him.

How Nirmal took this arrangement, what were Meera’s feelings for Rathi-da and her husband, the book gives little evidence, but the fact that Rathindranath’s letters to her were given to Jayabrato by his father Nirmal shows it was something that had his approval. Jayabrato’s reminiscence, added as a concluding piece to the book, describes a glorious childhood in the loving care of his jethu Rathindranath, who would often paint with his mother.

Visva-Bharati quickly forgot Rathindranath. At the book launch, Suvaprasanna spoke of how difficult it had been to try and find a good photograph of Rathindranath to use for a portrait he had wanted to paint. Talking of Rathindranath’s talent as an artist and his courage to be different, Suvaprasanna asked why the man was so vilified. “Khun to koreni, ektu bhalobashte cheyechhilo (he didn’t commit murder, all he wanted was to love)”. Rajat Kanta Ray emphasised Rathindranath’s contribution to build Sriniketan “from 1941 to 1951, when funds were hard to come by...”

Aparna Sen praised Nilanjan, who had acted in her film The Japanese Wife.