On the western banks of the Hooghly river, seven kilometres west of Calcutta, stands a fiery red brick building. It is the 200-year-old Salt Golah of Howrah — dilapidated, abandoned, a prisoner of aerial roots and creepers.

Salt golah means salt godown. This structure, however, is a collection of godowns — 206 in all. The location is no accident. Proximity to the waterways facilitated transport of salt to other parts of the country. The Salt Golah is all that remains of Bengal’s once-flourishing salt industry; today, Gujarat is known as India’s salt hub.

Cell No. 76 of the golah Photographs by Pradip Sanyal

That day, photojournalist and colleague Pradip Sanyal and I venture into the Salt Golah premises. Our guide is Railway Police Force (RPF) officer Tapas Kumar Chakraborty — the property is currently owned by the railways. “Watch your step! The place is infested with deadly snakes,” warns Chakraborty as we approach the iron gate on which is written — E. Rly. Old Salt Golah Area Kings Road, Gate no. 2. He pushes open the gate and from the very next second starts to tap on the ground with a long, thick stick, once to his right and once to his left, as he moves ahead, with us in tow.

Our first stop is a large room, light pouring in through an absent roof. The room is about 1,500 square feet, the size of a three-bedroom apartment, as are the rest of its 205 siblings.

On the opposite side, there isanother room with the number 150 painted on the wall. “The bricks those days were of such quality that to date, moisture has not left its white mark on them,” says Chakraborty.

The partially collapsed roof of a cell Photographs by Pradip Sanyal

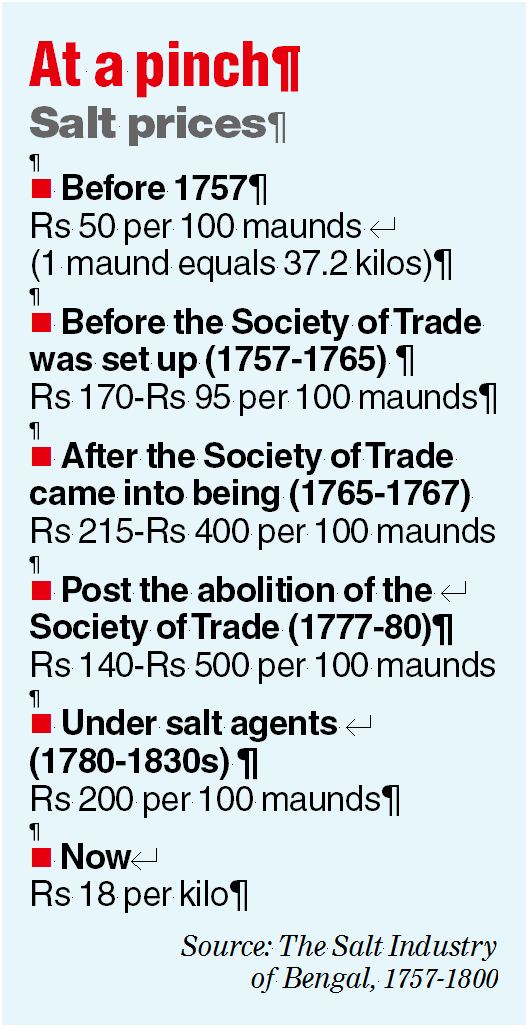

Salt-making is one of the oldest industries of Bengal. In the 18th century, the salt hub extended 700 square miles from Chittagong (in present-day Bangladesh) to Jaleswar (in Odisha) along the Bay of Bengal. In a paper, A.M. Serajuddin of the University of Chittagong writes that in the Mughal period salt was manufactured along the Bengal and Odisha coast by malangis. They did not make salt by solar evaporation, he clarifies, but by boiling concentrated brine, made by washing salt-rich soil with seawater. The way it was, the malangis worked on advances from salt merchants, who then distributed salt throughout the subah or province.

Balai Chandra Barui, who is in his eighties now, and is a retired professor of Kalyani University, has extensively researched the salt industry of Bengal. He has spent seven years in the West Bengal State Archives poring over the Salt Papers that document the history of the salt industry in these parts. He talks about how in the early days it was a free-for-all. The traders were mainly local people. According to Barui, there were indigenous Bengali traders, there were merchants and saudagars (traders) from Punjab, Multan, Gujarat and other areas. Before 1757, some Englishmen were also involved in their private capacity. Says Swapan Mondal, a research scholar, “Even Anthony Firingee — a trader of Portuguese origin who is an iconic figure in Bengal — was involved in the salt business.”

Space where the salt was weighed Photographs by Pradip Sanyal

In 1765, Robert Clive, the then governor of Bengal, formed the Society of Trade through which the East India Company established monopoly on salt, betel nut and tobacco. The committee comprised senior officials of the Company. Two years later, however, the society was abolished. Thereafter, the old zamindari system was revived and simple salt farming was followed for a while. At the end of the 18th century, the Company had divided the salt-producing areas of Bengal into six agencies — Hijli, Tamluk, the 24-Parganas, Raimangal, Bhulua and Chittagong — which were to run under salt agents.

The Howrah Salt Golah was constructed in 1835. G.M. Kapur, convenor of the Calcutta chapter of Intach, tells The Telegraph that Intach, along with the Eastern Railways, had been planning to restore the 58 buildings that make up the place. “There are 206 compartments with a combined storage capacity of 42,93,700 maunds or 1,59,000 tonnes,” he says.

Chakraborty says salt was most likely stored in jute sacks. The golah faces away from the river to avoid direct contact with the moist air and the buildings are at a level at which there would be no risk from the rising waters during high tide.

The salt commissioner’s office Photographs by Pradip Sanyal

At the centre of the vast acreage on the brink of oblivion stands a two-storey building facing the Hooghly. This used to be the salt commissioner’s office. Kapur says, “It was he who decided the price.” The arched verandah is strewn with dry leaves. There is a mango tree in front. “Snakes come to eat the fruits. They are very sweet. No one knows how the tree came to be here,” says Chakraborty.

The Howrah Bridge is visible from here. This was probably the spot where the salt arriving from distant places was offloaded and carried inside. There is a rail track, abandoned and half buried in the soil. Salt used to come in from Tamluk, Balasore, Puri and Cuttack and would be transported to other states. In his Bengali book Howrah Jelar Itihash, Achol Bhattacharya notes railway lines were set up in 1865 to facilitate the transport of salt.

According to Kapur, the property has great potential for adaptive reuse. Intach hopes to use it as a cultural and tourism hub with water sports and a marina.

The must-have list should include a salt museum and a son et lumière or light-and-sound show of Bengal’s salt legacy.

The Telegraph