|

|

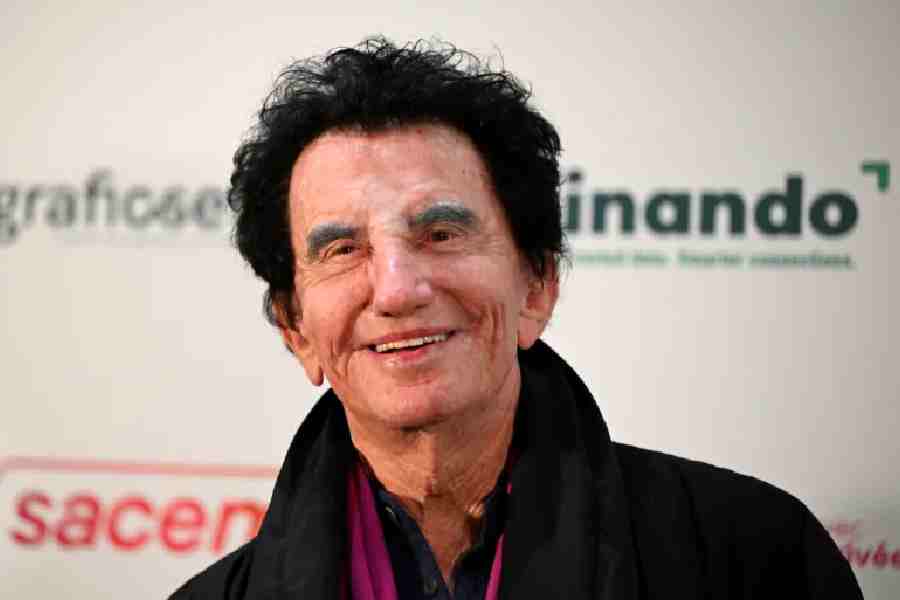

| Crab nebula, the first supernova remnant to be discovered, and (bottom) Supernova 1987A |

The material we see around us on the earth is made up of different elements, which differ from each other in their nuclear composition. But how were these elements formed and how did the earth, for example, end up having the heavier elements? Incredibly enough, all these heavier elements are synthesised from the hydrogen and helium at the central core of stars. When a star dies, these heavier elements are distributed in interstellar space through a gigantic explosion.

The last article explained how stars shine though nuclear power. These nuclear reactions fuse together lighter elements, starting from hydrogen and helium, to form progressively heavier elements. This process can keep the star shining for billions of years, but eventually the nuclear fuel in it will be exhausted. What happens to a star after that depends essentially on its mass. The most massive of stars can explode violently. This process, called a “supernova explosion”, spews the heavy elements cooked inside the star into the interstellar medium. Planets like earth form out of this medium and thus inherit the heavier elements. In that sense we are all children of stars.

At the end of the stellar evolution, the core of the star has exhausted its nuclear fuel and it collapses under its own weight, forming a neutron star. In a neutron star, protons and electrons combine to form neutrons. The energy released in the collapse of the core heats up the surrounding matter and ejects the outer layers in a gigantic supernova explosion. (To be precise, it should be called a Type-II supernova explosion since astronomers distinguish between two types of these explosions.) The “nova” in supernova stands for “new star” and actually describes an old star suddenly brightening up in a span of a few days, and — later on — slowly fading away in a month or two. During the brightest phase, such a star can outshine all other stars in its constellation and even change the shape of the constellation itself. This was dramatically confirmed in the case of a supernova explosion which occurred in 1987 — the first one to occur in the nearby after the invention of the telescope. It happened precisely at the location of a previously known massive star called Sk-69 202. As the supernova faded, it was clear that the star Sk-69 202 had simply vanished. Thus, for the first time, one saw a supernova arising from the explosion of a massive star.

It is estimated that there is one supernova explosion occurring somewhere in the universe every second; but, of course, most of them are too far away to be visible from earth. Supernova explosions in our galaxy or in nearby ones which are bright enough to be seen by the naked eye are estimated to occur only once in about a century — so, in that sense, it is a rare event. Two of the historically important supernova explosions were the ones that occurred in 1572 and 1604. The first one was studied by Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe and occurred in the Cassiopeia constellation; it was bright enough to change the familiar “M” shape of that constellation. The second one happened near a conjunction of Mars and Jupiter and thus was noted by astrologers all over the world. The systematic study of this supernova was made by Kepler. In the last millennium, only half a dozen supernova explosions occurred which were bright enough to be seen with the unaided eye.

The supernova explosions, of course, occur in interstellar space. Though the interstellar medium — containing about one hydrogen atom per cubic centimetre — is more tenuous than the best manmade vacuum, it is not completely empty. The explosive outflow from the supernova will sweep up the interstellar matter until the accumulating pressure can eventually bring the outflow to a halt. A supernova, thus, creates a hole in the interstellar medium surrounded by a shell of compressed matter. These objects — called supernova remnants — last for tens of thousands of years and can been seen in optical, X-ray and radio bands. A recent radio survey has seen more than a hundred such remnants in our galaxy. Optical identification often leads to a wisp-like nebula in that location. The first supernova remnant to be discovered was the crab nebula in the constellation Taurus, which is found at the precise location of a supernova observed by Chinese astronomers in 1054. Several other supernovas, like Kepler’s and Brahe’s, were likewise identified with remnants.

The central core, which is left behind by the supernova explosion, is usually a rapidly rotating neutron star. Such a rotating neutron star will send out periodic pulses of radiation at regular intervals, thus earning the name “pulsar”. This is another bizarre cosmic object which we will consider in the next article.

T. Padmanabhan is an astrophysicist at the Inter-University Centre for astronomy and Astrophysics, Pune