|

|

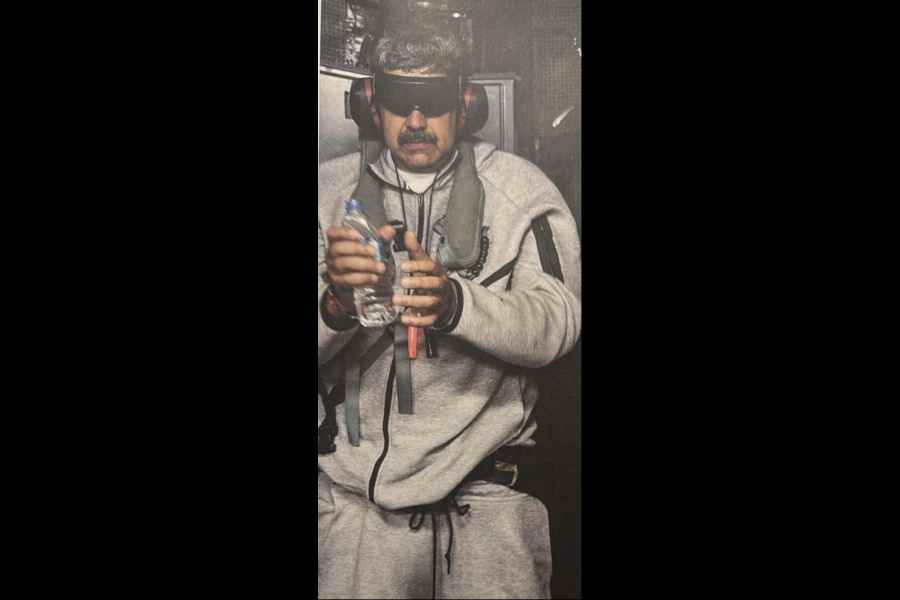

| NRIs celebrate Independence Day at Madison Avenue, New York |

“A very important period of my life was spent in Lahore and Faisalabad. I wish to be citizen of both India and Pakistan.” — Sisir Kumar Bose, August 15, 2000

“Citizens of other countries (including Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, and Pakistan, for example, regarding which some apprehensions have been expressed) would not be eligible for India’s dual citizenship.” — Report of the high level committee, January 2002

“We are in favour of dual citizenship but not dual loyalty.” — Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, January 2002

The public demand for dual citizenship of India and Pakistan cited above was made by an Indian nationalist, one of the last surviving members of the generation that had taken part in India’s struggle for freedom from British colonial rule. He had endured baton charges and jail in Calcutta, and spent a good part of his youth, some of it in solitary confinement, in the dungeons of Red Fort and Lahore Fort and in Lyallpur Jail for “acting in a manner prejudicial to the defence of British India”. He wrote of his wish to be citizen of both India and Pakistan in a special article on India’s Independence Day [Sisir Kumar Bose, “Jatiyatabadir Atmasamiksha” (Introspection of a Nationalist), Ananda Bazar Patrika, August 15, 2000]. He was eighty when he wrote it and died shortly after its publication.

The disarmingly direct demand contained a double whammy for the Indian government. Not only did it advocate dual citizenship, which has long been obdurately opposed by the government of India, but it also plainly asked for the very thing that drives India’s fear of dual nationality — “the apprehension that Pakistanis and Bangladeshis might gain access to India’s dual citizenship” — as the report of the high level committee chaired by L.M. Singhvi put it.

The committee was set up by the government of India in September 2000 to look into the Indian diaspora. In its report, submitted in January 2002, it recommended dual citizenship for India.

The “apprehension” about India’s neighbours, the committee reports, was the only negative concern it received from the wide range of distinguished persons whose opinion it sought. It dealt with it by restricting dual citizenship to a select group of countries — the United States of America, countries of the European Union, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Singapore and so on. “The Committee has made it amply clear....that citizens of other countries (including Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, and Pakistan, for example, regarding which some apprehensions have been expressed) would not be eligible for India’s dual citizenship.” Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee accepted the committee’s report with a characteristically enigmatic remark, “We are in favour of dual citizenship but not dual loyalty”, which, as always, might be a sign of deep reflection, or none at all.

However, the prime minister’s reference to the issue of loyalty rakes up a longstanding clash of perspectives between Indians at home and Indians abroad. It is the latter, generally referred to as NRIs (non-resident Indians) and more recently as PIOs (persons of Indian origin), that are perceived to be lobbyists for dual citizenship. The mother-country’s generosity of spirit towards them appears to have been limited to the creation of ever new acronyms that continued to keep them suspended in a nebulous range between citizen and alien. Instead of appreciation for their accomplishments abroad they faced envy. Rather than being viewed as assets they were branded as disloyal and accused of abandoning their motherland for the sake of a washing-machine. Never valued for their professions or talent, they seemed to be viewed as roving money-bags, to be remembered only when India landed in a spot of financial bother and needed a bail-out. Their emotional attachment to India met with shabby rejection. Their quest for dual citizenship was put down to all sorts of dubious motives, including a ploy to avoid visa fees. India never acknowledged that to Indians abroad, dual citizenship might be a crucial part of identity, a sense of belonging.

The high level committee’s report rebutted many of the illogical and self-damaging aspects of India’s opposition to dual citizenship, which has been powered for decades by prejudice and paranoia rather than policy analysis. It noted that more than 70 countries had dual citizenship and more were on the way. Indeed, in the wider world one has come across dual, triple and in at least one case quadruple nationality, all acquired perfectly legally without any obvious hazard to global security. It is not clear how Prime Minister Vajpayee expects to have dual citizenship without dual loyalty, but in normal circumstances there need not be any conflict of loyalty between different manifestations of a person’s multiple identity. The committee was also refreshingly sensitive to the NRIs’ true need for dual nationality: “The principal rationale of the demand of the Diaspora for dual citizenship, however, is sentimental and psychological...”. This also explained why there were few takers for the PIO scheme, which offered practically all of the same practical benefits.

Incidentally, both Pakistan and Bangladesh, whose supposedly nefarious intent forms the core of India’s irrational fear of dual nationality, have had dual citizenship for a while. Pakistan’s duality arrangements are also restricted to a select list of countries that includes several European and west Asian countries, Australia, New Zealand and Canada. A recent confusion over an ordinance that seemed to affect dual citizenship with the US has just been clarified in favour of duality. Bangladesh offers dual citizenship to its own citizens as well as foreigners with major investments in Bangladesh.

India’s citizenship laws were quite liberal at the dawn of independence, perhaps because the new country had to accommodate potential citizens residing in other parts of the British empire or migrating from what became Pakistan. Citizenship is acquired by birth, descent, registration or naturalization. Neither the Constitution nor the Citizenship Act of 1955 expressly dealt with dual citizenship, though Article 9 of the Constitution and Section 9 of the Citizenship Act refer to the termination of citizenship if someone “by naturalisation, registration or otherwise voluntarily acquires” the citizenship of another country. Apparently aimed at adult migrants, this provision does not address “natural” acquisition of multiple nationality by birth and descent or the interplay of India’s laws with those of other countries. The committee’s report also notes a ruling that “obtaining of a passport from another country does not necessarily imply exercise of free volition”.

After the fanfare of official acceptance, the recommendation of dual citizenship duly vanished into the black hole of official scrutiny. However, if it is ever implemented, Indian citizenship, the “badge of belonging” in the world of nation-states, would be shared with alien lands with advanced economies, but would expressly exclude one’s closest kin, fellow-members of the south Asian subcontinent.

In the European Union, by contrast, regional economic integration has been followed by degrees of political federation. France and Germany, past enemies with a history of bitter conflict, today share a common currency and a common passport. India is at last warming to the idea of embracing dual nationality with Canada or Japan, but finds it imperative to couple the concept with assurances of having nothing to do with Pakistan and Bangladesh.

As India’s relation with its neighbours varies from a virtual state of war to just unfriendly, joint citizenship may not be immediately practicable. However, it is no secret that the hostility among south Asian states is in direct conflict with the interests of their people, who would be far better served by economic integration and political cooperation. The ultimate goal therefore should be not the exclusion but rather the eventual inclusion of neighbouring states in a common south Asian identity.

While India plays catch-up with dual citizenship, identity and sovereignty are being redefined around the world, whether through integrative movements as in Europe or in fissiparous tendencies in existing states. One reason for this is that the contrived construct of the nation-state does not always fit the identities or interests of the people it holds in its iron embrace. The generation whose dreams of freedom — and sense of belonging — encompassed all of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, is nearly extinct. The truncated bits pose a dilemma for their descendants. As a Bengali, my sense of kinship with Bangladesh is far greater than with any other part of the state of India. It is absurd to expect a greater sense of identity with Arunachal Pradesh than with Baluchistan merely at the diktat of the nation-state. Ironically, the sense of belonging seems to make more sense at the level of a region of India or the subcontinent as a whole, than the territorial construct in-between with the power to bestow citizenship.