On October 15, 1947, two months after Independence and Partition, India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, wrote to the chief ministers of provinces saying: “Whatever the provocation from Pakistan and whatever the indignities and horrors inflicted on non-Muslims there, we have got to deal with this minority in a civilized manner. We must give them security and the rights of citizens in a democratic State.”

Nehru’s commitment to secularism and equal rights for minorities was not universally shared even within his Congress Party, which had its fair share of conservative Hindus. However, as prime minister, he himself worked assiduously to marginalise the forces of Hindutva as represented in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and the Jana Sangh. It was only in the decades after his death that the RSS and the Jana Sangh’s successor, the Bharatiya Janata Party, grew rapidly in influence. As a result, our nation, which after August 1947 hoped to chart a different, more inclusive, path from its neighbour, is now coming ever closer to Pakistan with regard to the merging of faith and State.

The majoritarian cast of India today is manifest in the fact that of the over 800 members of Parliament elected on a BJP ticket in the last three general elections, not one is a Muslim. Under Narendra Modi and Amit Shah, the BJP has sought to create a Hindu vote bank, fighting and often winning elections on the basis of the support of Hindus alone. Once a Hindu-first politics propelled them to power, the sangh parivar has consolidated its dominance socially, through harassing and demonising Indian Muslims (and on occasion Indian Christians too).

Once, Muslims held important cabinet posts, ran major government departments (including the diplomatic corps and the Intelligence Bureau), headed the Supreme Court and the Indian air force. Indeed, within living memory, two cities in Narendra Modi’s home state sent Muslims to represent them in Parliament. Now, however, there is hardly any Muslim in a position of prominence in public life. As for working-class Muslims, they are subject to discrimination in housing and employment, and to routinised taunting and humiliation, which quite often takes the form of targeted violence (as in lynchings and house demolitions).

Hindu majoritarianism is also manifest on the legal front. The Citizenship (Amendment) Act clearly discriminated against Muslims, and the abolition of Article 370 was not unrelated to the fact that Jammu and Kashmir was India’s only Muslim-majority state. At the symbolic level, the majoritarianism is visible in the saffron robes of the chief minister of India’s most populous state, and in the prime minister presiding over the inauguration of the new Ram temple. This signalling by our most powerful politicians encourages senior public officials to likewise openly violate constitutional norms and behave as if they were Hindus first and Indians only later. Hindutva has also penetrated popular culture, with Bollywood, once a bastion of secularism, now increasingly prone to showcasing films that portray non-Hindus in poor light.

The open avowal of majoritarian bigotry is being manifested, as I write this, in the BJP’s campaign for assembly elections in Assam and West Bengal. Speeches by the party’s leaders, and by the Union home minister of India and the Assam chief minister in particular, are aimed at goading Hindus to fill their minds and hearts with hate for Indian Muslims. That the higher judiciary has not (at the time of writing) checked either politician is shocking, yet also symptomatic of the moral degradation of our public institutions.

In politics and in law, in symbol and in substance, in word and in deed, India is therefore becoming ever more like Pakistan, except that here it is Hindus, and not Muslims, who rule over fellow citizens who are of other faiths. In explaining the dominant position of Hindu majoritarianism today, one must however emphasise that this does not all date to May 2014. It has far older roots. There is a deep history of Hindutva, whose milestones include the activities of Hindu missionary societies in the 19th century, of the Hindu Mahasabha in the 20th century, and the founding of the RSS in 1925.

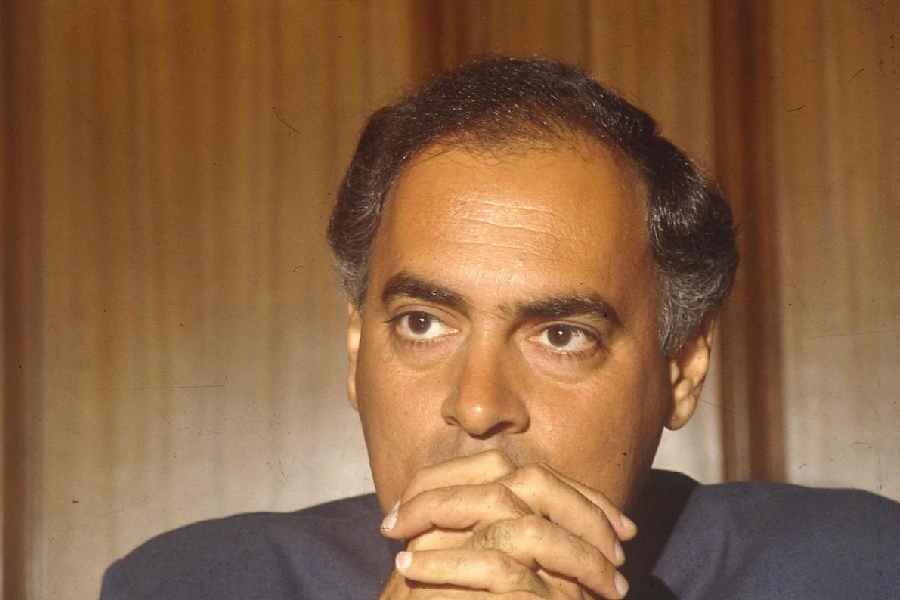

In the years when Jawaharlal Nehru was prime minister, Hindutva was recessive. Yet it was always there in the background. The Hindu Right was given the opportunity to grow and expand through the errors of the post-Nehru Congress. Particularly culpable here was Rajiv Gandhi, who, as prime minister, appealed to Muslim hardliners by overturning the Shah Bano judgment of the Supreme Court, and to Hindu hardliners by opening the locks to a tiny shrine in Ayodhya adjacent to the Babri Masjid. Of these misguided acts the journalist, Neerja Chowdhury, warned at the time that “a policy of appeasement of both communities being pursued by the government for electoral gains is a vicious cycle which will become difficult to break.” The left-wing MP, Saifuddin Choudhury, was more blunt, saying that while Rajiv Gandhi spoke of taking India into the 21st century, his actions suggested that “he has a mind as primitive as the mullahs and the pundits”.

Nehru strove to keep religion out of politics. His grandson brought it in, cynically and instrumentally. Rajiv Gandhi’s policies only played into the hands of the BJP. For, once his government made religion the basis of statecraft, it was inevitable, given the asymmetry in their populations, that Hindu extremists would benefit far more than Muslim extremists. The opening of the locks in Ayodhya emboldened the sangh parivar to launch a countrywide movement to demolish the Babri Masjid and build a grand temple to Ram in its stead. The BJP won a mere 2 seats in the 1984 elections, yet within a decade-and-a-half had emerged as the leading party in the country.

The majoritarian instincts of the first BJP prime minister, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, were constrained by his party having to work with many coalition partners. The second BJP prime minister enjoyed two successive parliamentary majorities, and even when falling slightly short the third time, has shown himself to be ruthless in his prosecution of a Hindu-first agenda. Narendra Modi and his right-hand man, Amit Shah, are far more committed ideologically, as well as far more focused on winning and retaining power, than the current generation of Congress dynasts, whose interest in politics can appear episodic and erratic. As a result, the sangh parivar has steadily grown in influence and power, while the Congress has atrophied and decayed.

The ideologues of the Hindu Right sometimes claim that what is unfolding in India today is a ‘civilisational renaissance’. This is utterly untrue. The leaders and cadres of the BJP and the RSS are anti-intellectual philistines. They have little interest in the great achievements of Indian art, architecture, music, or philosophy, and no desire to make these relevant to the contemporary world. Their interest lies elsewhere; in proclaiming the political, economic, legal, and institutional superiority of Hindus over those Indians who are not Hindus, and over Muslims especially. What

we are witnessing in India today is therefore not civilisational renewal, but the assertion of a nakedly majoritarian agenda.

All in all, India in 2026 is as close to being a Hindu Pakistan as it has ever been before. Can this be reversed, and a secular, non-denominational State be nurtured in the future? That, alas, is a question impossible to answer. However, when one looks at the experience of other countries, it appears that the merging of faith with State has not worked out well anywhere. Making Islam central to the identity of Pakistan deeply damaged its economic and political prospects. The abandonment of the secular principles on which it was founded is increasingly hurting Bangladesh. Iran had all the economic and cultural potential to be a developed country; that hope and ambition were destroyed by fundamentalist Ayatollahs after they came to power in 1979.

Nor is it only Islamic countries that suffer through majoritarian assertion. Back in the 1970s, Sri Lanka was well ahead of India when it came to education, health, gender equality, and other markers of development. Had it not been for the rise of Sinhala Buddhist chauvinism, and the civil war it ignited, Colombo and Kandy could, like Bengaluru and Hyderabad, also have emerged as centres of the IT revolution. Finally, the State of Israel, so beloved of our Hindutva brethren, is becoming a pariah in the world system through the war crimes enabled by the most reactionary trends in modern Judaism.

Making the religion of the majority central to the public identity of a nation, designing laws, policies and institutions according to the wishes of mullahs, priests, monks or rabbis, has had disastrous results in countries that are variously Sunni, Shia, Buddhist, or even Jewish. There is no reason to suppose that Hindus are somehow exempt from this rule.

ramachandraguha@yahoo.in