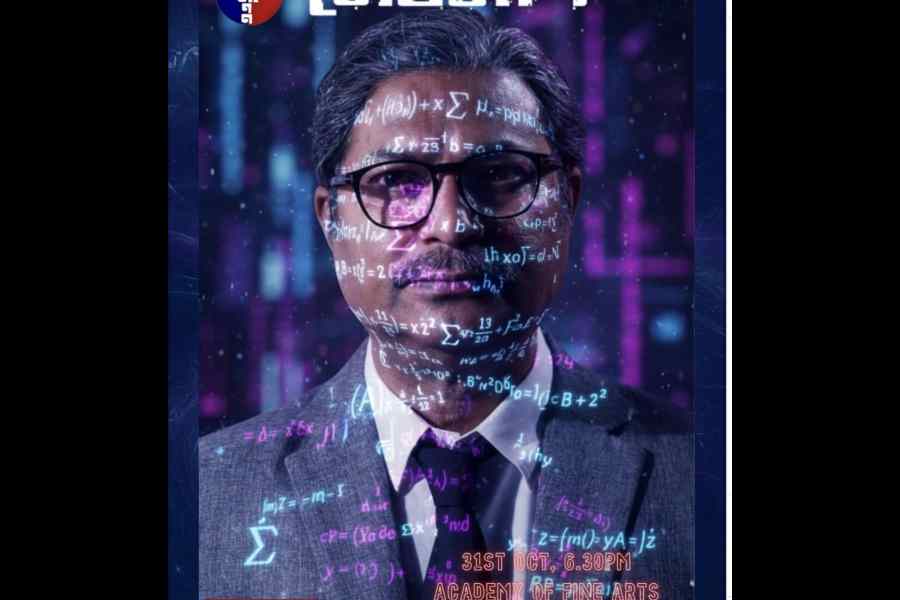

The Bengali play Meghnad — staged by theatre group Ashoknagar Natyaanan — has been written by Sudipta Bhawmick, who is an IIT Kharagpur alum and an artificial intelligence and machine learning expert based in the US.

He tells The Telegraph, “A few years ago, I came across Abha Sur’s book Dispersed Radiance. In it, she discusses the effect of caste politics on Meghnad Saha’s life and work, which I thought would be an interesting premise for a play. I started researching Professor Saha’s life and work, but it kind of died down.”

Saha was an astrophysicist who built the first cyclotron in India and translated Einstein’s original papers into English along with friend and fellow scientist Satyendra Nath Bose. He is also the only scientist of his stature to be elected to the Lok Sabha and he was instrumental in setting up the iconic Planning Commission.

Possibly around the same time when Bhawmick was reading Sur’s book, here in Calcutta, television actor and theatre artiste Chandan Sen was thinking of a play on Saha. Sen had been called to audition for a role in a web series about Homi Bhabha. It was of Bhabha’s nemesis, a Bengali Muslim scientist. The character was clearly modelled on Meghnad Saha. Says Sen, “They showed him in a negative light. I wanted to correct that.”

When Bhawmick and Sen met at an adda session in Calcutta, dots joined and things flew into place. Says Bhawmick, “Chandan expressed his interest in doing a play on Meghnad Saha and requested me to write it.”

Bhawmick, who had written “science plays” before this, took two years. Sen talks about how he consulted multiple scientists. “The idea was to portray Saha the man, the thinker who wanted to use science to improve the lot of common people, the humanist who thought nuclear science should be used for the welfare of the people.”

Satyaki Bhattacharya, who is a senior professor at the Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics, was one of those scientists who helped shape the play. The play brochure has on it his quote: “Meghnad Saha was among those geniuses inspired by rational thinking who fought to build a modern India. ...Considering the times we live in, it has become necessary to get reacquainted with Meghnad Saha the man.”

Opening scene of Meghnad. The Institute of Nuclear Physics in Calcutta. Period: 1953-54. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru is supposed to visit the lab that day but the cyclotron is malfunctioning. Cyclotron is the name for a class of devices used to “accelerate charged atomic or subatomic particles in a constant magnetic field”.

When his juniors worry that the mechanic won’t get there in time, Saha reminds them that they know enough to do the job themselves. “Or are you ashamed of getting your hands greasy? Do you think such work is below your dignity?” he roars.

“This separation of the thinkers and the doers, the brain and the hand, this caste system is the reason that science has not progressed in our country,” Saha laments.

Chandan Sen has directed the play in which he also plays the older Saha, while Rwitobrato Mukherjee plays Saha’s younger self. Shantilal Mukherjee plays Nehru and Rajatsubhra Bhattacharya plays Homi Bhabha.

By way of prepping for this role, Sen read up on Saha and met with some of his

children. He speaks of Pitri Tarpan, the book written by Saha’s third daughter, Chitra. This exploration, he says, has distilled his understanding of the scientist.

The whole process has unearthed details about the man, long forgotten by newer generations. For instance, in the play brochure, physicist and professor Gautam Gangopadhyay makes a reference to the story of Saha changing his own first name.

At birth, he had been named Meghnath, meaning, the god Indra. But he changed it to Meghnad, defeater of Indra and hero of Michael Madhusudan Dutt’s Meghnadbadh Kabya, ahead of his school-leaving exam. Gangopadhyay writes, “It was his first loud protest against the caste system.” In Bhawmick’s play, S.N. Bose narrates this story to Acharya Prafulla Chandra Roy.

Meghnad is not a linear play. It is a selection of events from Saha’s life that illustrate

the juggernaut of caste in every sphere.

This curation has met with criticism — the play was staged for the first time this year in September at the Academy of Fine Arts. The second and third shows, on October 31 and November 8, were also held there. At the second staging, a member of the audience pointed out that Saha’s contribution to river planning was missing, another grumbled that it made no mention of Saha’s ionisation equation.

Astrophysicist Sandip Kumar Chakrabarti of the Indian Centre for Space Physics in Calcutta says, “Not only can the Saha ionisation equation measure the temperature of stars, it was also important for understanding the origin of cosmic microwave background.” Sen too laments they could not accommodate the story of Saha’s planned scientific calendar. But his point is that the curation of events, the emphasis on caste and coteries, was necessary. “It is a biopic with a purpose, and that is to show that science must be accessible to all. We, in India, talk about racism but India is the birthplace of exclusionism,” says Mukherjee.

Bhawmick points out how Saha was ignored both by the international community as well as the Indian scientific and governmental organisations.

The play, which is framed by Nehru’s visit, ends with a rather charged interaction between the scientist and the first Prime Minister. Saha excitedly accuses Nehru of misusing science and Nehru makes his own calm defence. But the disagreement does not translate into a disconnect, at least not for Nehru. He hails the rather disillusioned and embittered Saha as a “live cyclotron” propelling his students towards a better society.

And as he leaves the stage he tells Saha, “Don’t stop criticising me.”

Some things have certainly changed.