Barely 3am, the shutters of every shop of central Calcutta’s Taltala Lane are down, all doors and windows shut tight to keep out the winter chill. At the far end of the lane,

a door is ajar, a group of four men steps out, they are sweating profusely. In their hands are yellow and blue crates full of bread — small and big loaves, some sliced, some unsliced, some twisted, buns — which they put down outside the door. The air inside the dark and dinghy lane is fragrant with the smell of wood fire and flour, of spices and caramelised sugar.

And all the while, at the other end of the lane someone is waiting.

Hasibul, 35, used to work in an embroidery workshop in Delhi five years ago, but he left it to join the local bakery business.

He is a vendor, a peg in the mid-sized machinery of indigenous bakeries and vendors servicing Calcutta and its outskirts for the last 50 years.

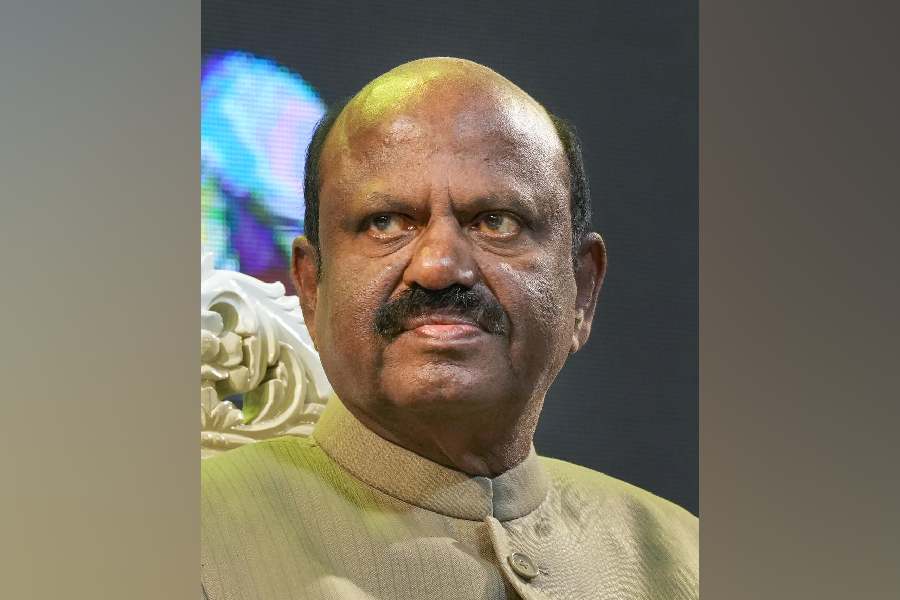

A bakery in central Calcutta.

There are 300 to 350 bakeries in the city, most of them in areas such as Taltala, Tollygunge, Behala, Garia, Baghajatin, Park Circus, Rajabazar...

“These bakeries employ close to 4,000 people directly,” says the secretary of the joint action committee of bakers of Calcutta, Sheikh Atiar Rahman, who also owns Luna Bakery.

A bakery in central Calcutta.

Wait over, Hasibul loads onto his cycle van about seven crates from three different places in the same neighbourhood. It is 4.30am. These are the local bakeries. The baking happens the evening before, the bhatti or clay ovens fall cold and empty by 3-4am. Once the bakers are done, it is time for the slicing, packing and stacking.

Every bakery has a set number of vendors servicing select neighbourhoods and shops.

New Howrah Bakery, better recognised as the company that makes Bapuji tiffin cake, is the biggest player in this market. Every morning, around 20 vendors on as many cycle vans set out from the bakery in Dhulagarh and spread across the satellite city. Says Amit Jana, who is the co-owner of New Howrah Bakery, “A chunk of our bakes also travels in trains and buses to Nadia, Midnapore, Hooghly, Bankura...”

A bakery in central Calcutta.

Rahman says, “From Taltala, we send bread to Kidderpore, Bhowanipore, Behala, to college canteens, sporting clubs and government offices in central Calcutta. They have been our clients for ages.” He adds, “This line of products is for the common man. Our bread slices are thick and keep you full for a longer period of time.”

Hasibul’s cycle van rolls out of Taltala. The wheels churn the darkness, in silence he weaves his way from one lane into another with names such as Sandal Street, Pemantle Street, Marsden Street... His GPS is inside his head, his client list also seemingly burnt into his brain.

Between 4 and 6am, Hasibul makes at least 12 stops. He goes inside each shop, takes stock of what it has, accordingly selects from his wares, offloads and arranges them, scribbles details in a notebook, makes the shopkeeper sign and leaves.

His clients are mostly corner shops, the kind that stock stationery and also paan and cigarettes, chips and biscuits. There are some individuals milling around these shops; they seem to know Hasibul, the route he takes and the timing he keeps.

“I need a fresh consignment before sundown,” says one shop owner. Shamim Khan, another buyer, explains, “This loaf of bread is suitable for all kinds of things. You can have it for breakfast, or you can eat it with meat for dinner. It suits all.”

At the next stop, an old man is waiting for Hasibul. He is a buyer. He is waiting to get a fresh loaf of bread for his grandchild’s tiffin. “I have been eating this bread since my childhood. I am 60-plus. Now my granddaughter takes it to school. The shopkeeper will spread butter on each slice of a quarter-pound loaf. It is going to remain soft for the next four to five hours,” he says and hurries away.

Hasibul stops at a cha shop finally. It is 6.30am. There are some men in winter caps sipping hot tea from bhnars. Hasibul is running late. He says, “Once I am done with this, I have another job. I manage a small shop.”