Book: THE TREE WITHIN: THE MEXICAN NOBEL LAUREATE OCTAVIO PAZ’S YEARS IN INDIA

Author: Indranil Chakravarty

Published by: Penguin

Price: Rs 699

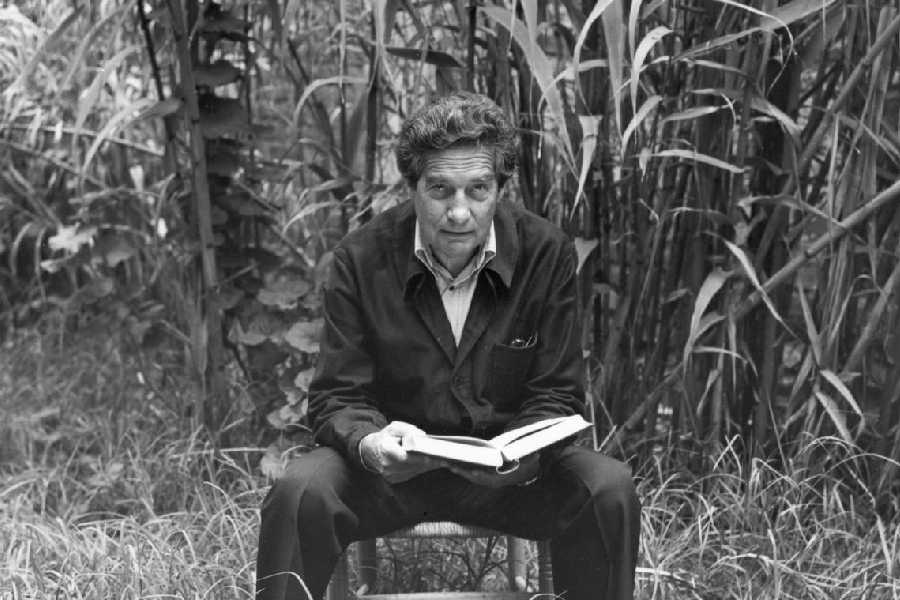

This is one of the first book-length works about Octavio Paz and how his work bridges the roughly antipodean terrains of Mexico and India. It’s also notable because, according to Susnigdha Dey, most attempts to trace India in the works of foreign writers have been limited to English, French and German languages. Paz’s experience of India differs from that of his fellow Spanish-language writer, Pablo Neruda, because Paz’s visit as an ambassador — an authoritative and political capacity — is presumably differently-motivated than that of an otherwise supremely-gifted aesthete tourist. As Malabika Bhattacharya notes, he was able to “penetrate the touristic mask that we put on in front of foreigners”. His poetry, like that of Tagore, seems to be suffused with a pithy self-regard and effortless weightiness, with rarely a preamble; these are assumed to be marginalia, borne by people to the manner born, living through hard times in a nation bellowing for revolution.

The book’s initial forays into Paz’s life are a veritable roll call of historical figures: Francisco I. Madero (the legendary leader of the Mexican Revolution, with

the Bhagavad Gita in one hand), Annie Besant, Jiddu Krishnamurti (and his way with the Upanishads), Jagdish Swaminathan (the Indian painter) and, later, Satish “Gujrat” Gujral, as Paz misspelt him, among several others. José Vasconcelos (a leading Mexican

philosopher and a cultural bulwark of the Mexican Revolution) and, later, Paz would go on to theorise about, as Chakravarty writes, “the emotions of poetry, erotic love and religious fervour”. A jingoistic, masculinist notion, yet one notes yearning and drive, the loss of diurnal discretion that ties the two zealots together.

The most constant feature in Paz’s poetry, as noted by Enrico Mario Santí, is the “analogy between the woman’s body and the world”. This clasps the opposing frontiers of poetry being social commentary and personal self-regard. The Swedish Academy’s citation recognised his “... sensual intelligence and humanistic integrity”. It is arguable that his writing, beginning from the 1960s, coinciding with his proper initiation to India and marrying his second wife there, was his most productive and diverse. His adhesion to new cognitive structures, including those from Japan, is sublime, and his work begins to assume more auteurist overtones as he lets go of earlier notions of form and overture. He begins to examine analytic philosophy and structuralism, including threads borrowed from Buddhism, and minor symptoms into a grander narrative of our lives as “other people”. His poetry champions a sophisticated notion of cosmopolitanism. His body of work is burgeoning with poignant, uncommon themes such as the silence of the Hindu temple, finally free of the reedy nadaswaram, or the implosive meeting of opposites (“If you are the wind’s leap/ I am the buried fire”, from “Motion”, translated by Eliot Weinberger). The New York Times book review would go on to call him “an intellectual literary one-man band”.

Chakravarty’s work is an exercise in perpetual essay-writing and escapes the confines of a biography. He had planned a film that would sadly not ever be made. In turn, his book performs the cinematic technique of the extended long take where chapters begin before Paz, chronicle him and watch him walk away, instead evaluating the paraphernalia that would go on to constitute him. Several times a character (in his/her own right a living person) is named and is pictured a few pages later. The unintended effect is of mythology and a sweeping theatrical reveal. It is a consummate work of deep scholarship, which is strident and doesn’t treat its subject matter as a niche artefact for studied pretence. It’s national history. In much the same way as Paz was fascinated by T.S. Eliot and wrote for a while in a similar tradition, taken by the mystical doctrines of Indian philosophy, Chakravarty approximates his subject by not ever meeting him but drawing him in the aggregate through a magnificent meshwork of his work and his friends, including Gujral, who couldn’t sleep the night before the author interviewed him for the book.

One imagines Tagore and Paz zooming through the pulp of the earth, shoring at the other’s native countries, and finding not much out of place. What a staggering piece

of work.