I first met Khaleda Zia when she visited Delhi in 2013, at a time when I was joint secretary holding charge of Bangladesh. It was, in many respects, an exceptional outreach by our government to invite the principal face of the Bangladeshi Opposition, notwithstanding a long history of animosity and despite our close working relationship with the then Prime Minister and her arch-nemesis, Sheikh Hasina.

The decision to engage Khaleda Zia reflected a conscious recognition in New Delhi that India-Bangladesh relations could not be reduced to a single political alignment, however comfortable that alignment may have been. Bangladesh’s politics had long been bipolar, and stability in the relationship required engagement across that divide.

I had occasion to meet Khaleda Zia often during my subsequent tenure as high commissioner in Dhaka. In person, she was invariably charming and courteous, although one could easily imagine that she could be equally stern and daunting if circumstances demanded it.

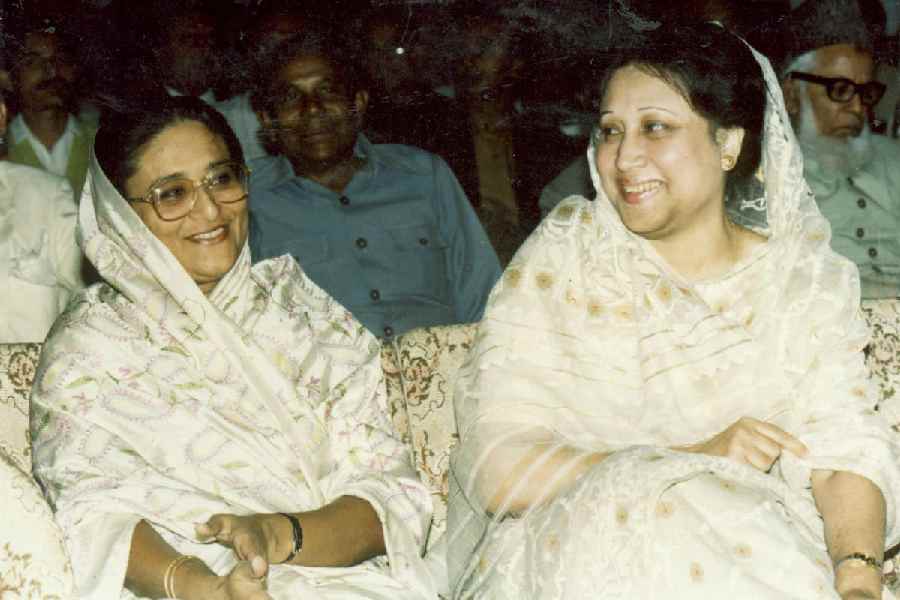

Khaleda Zia (right) and Sheikh Hasina

There was a quiet authority about her, forged over decades at the centre of Bangladesh’s turbulent politics. She was gracious in receiving my gift of Darjeeling tea when I first called on her in Dhaka, a small but symbolically resonant gesture.

The meeting itself was formal, replete with pleasantries and protocol. Yet, even within that formality, there was a discernible effort on her part to soften old edges, to signal a willingness to rebuild bridges and address earlier estrangements.

This was not without context. Khaleda Zia’s second term as Prime Minister (2001-2006) had been one of the most difficult phases in India-Bangladesh relations. That period was marked by pronounced anti-India rhetoric, Bangladesh’s reluctance to address Indian concerns regarding insurgent groups operating from its territory, and a strategic posture that leaned more visibly towards Pakistan and certain Islamist constituencies.

New Delhi’s frustrations during that time were not merely ideological; they were grounded in concrete security concerns, particularly relating to India’s Northeast, as well as stalled cooperation on trade, transit and connectivity. Those years bore a deep impact on Indian strategic thinking about the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, shaping a perception that endured well beyond her time in office.

Against that backdrop, even modest gestures of outreach in her later years acquired significance. My attending her iftar during Ramzan was unprecedented and took her visibly by surprise. It was a necessary and conscious signal that India was prepared to move beyond the accumulated mistrust of the past.

I maintained contact thereafter with her and with her advisers. Her advisory circle comprising senior politicians, former diplomats and retired military officers was notable for its calibre. They were individuals of experience and depth, with a clear understanding of Bangladesh’s regional environment and strategic compulsions. That Khaleda Zia identified, trusted and retained such figures speaks to her political instincts. She valued competence and loyalty in equal measure, an increasingly rare combination in deeply polarised systems.

Equally striking was her ability to hold together the BNP and the wider Opposition during a period of sustained political stress. Bangladesh’s politics in the past decade has been unforgivingly characterised by contested elections, prolonged agitation, institutional pressures, and eventually her own imprisonment on corruption charges. Yet Khaleda Zia’s authority over her party endured even when she was physically removed from the political arena.

That capacity to command loyalty without office underscored her stature as more than a transactional leader; she was, for her supporters, the embodiment of a political tradition.

Often described as a beauty in her younger years, she was married early and lived through extraordinary personal upheavals. In 1971, her husband, Ziaur Rahman, then an officer in the Pakistani army, raised the banner of revolt in favour of Bangladesh’s liberation. That moment not only altered the course of the country’s history but also irrevocably reshaped her own life.

She was not a politician by choice or ideological inclination, but by circumstance. Following Ziaur Rahman’s assassination in 1981, Khaleda Zia was drawn into public life, navigating roles for which she had no formal preparation — party leader, Prime Minister, Opposition icon, and ultimately a symbol of resistance.

She bore these transitions with notable stoicism. From serving twice as Prime Minister to years of political marginalisation and incarceration, she accepted reversals as part of the burden of public life. There was a sense of noblesse oblige in how she carried herself, an understanding that leadership entailed endurance as much as authority.

Over time, her political posture also evolved. While her earlier years were marked by ideological rigidity towards India, her later engagements suggested a more pragmatic appreciation of geography, economics and regional interdependence. Her meetings with Indian leaders in her final years, including her interaction with Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Dhaka in 2015, reflected that gradual recalibration.

In the end, her passing appears to have opened the way for her son, Tarique Rahman, to step fully into the family’s historic political role. In a sense, Bangladeshi politics has come full circle, returning to the dynastic rhythms that have long defined it.

Khaleda Zia, despite her later efforts at engagement, remained for many in India a symbol of an alternative political order that was less accommodating of Indian interests. Her death removes that symbol but not the underlying political constituency she represented.

The immediate implication is that India can no longer rely on personal equations, positive or negative, to anticipate the direction of Bangladeshi politics. A Bangladesh Nationalist Party led by Tarique Rahman will not automatically inherit Khaleda Zia’s instincts, constraints, or experiential understanding of India.

Tarique belongs to a different generation, shaped less by the Liberation War and more by contemporary narratives of sovereignty, nationalism and electoral mobilisation. For India, this means that engagement with the BNP can no longer be mediated through legacy assumptions; it must be rebuilt on clearer terms, grounded in mutual interests rather than historical baggage.