A passage quoted often on mid-19th century Burrabazar describes how grand the market was. “Here may be seen the jewels of Golkanda and Bundelkhand, the shawls of Cashmere, the broad cloths of England, silks of Murshidabad and Benaras, muslins of Dacca, Calicoes, ginghams, Chintzes and beads from Coromandel, fruits and firs of Cabul, silk fabrics and brocades of Persia, spices and myrch from Ceylon, Spice Islands and Arabia...,” writes artist Colesworthy Grant in his book An Anglo-Indian Domestic Sketch, published in 1849.

Spices were always important: the spice trade had opened up the first world routes, on sea and land.

Grant, of course, is talking about exotic spices along with other global luxury items. But Burrabazar is, and was, a great leveller. Alongside fine, expensive and even borderline-mythical products —tiger’s milk is also available here, it is said — the everyday stuff exists here with a fierce abandon, giving Burrabazar its character.

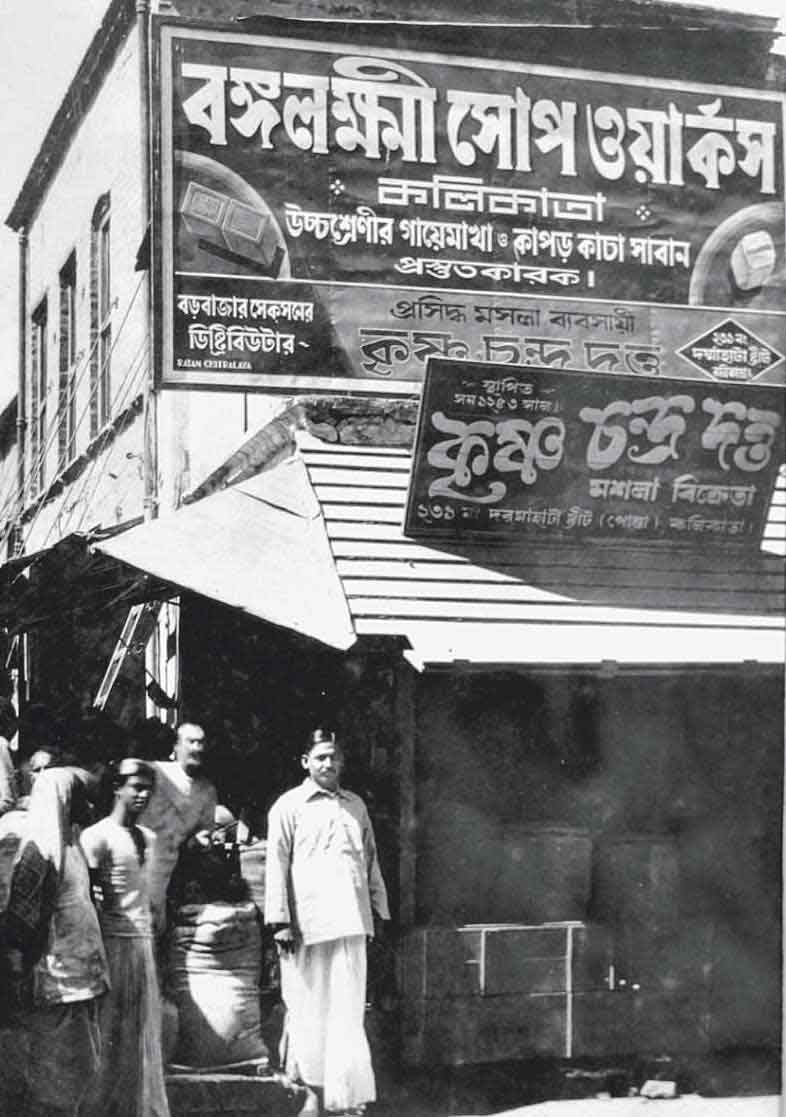

Three years before Grant’s account was published, in 1846, Krishna Chandra Dutta, a resident of Saptagram, Hooghly, had settled down in Sutanuti and set up his shop with his brother in Dormahata in Posta, a part of Burrabazar. They sold whole spices that were used in day-to-day Bengali cooking: chillis, turmeric, cumin, getting their supplies from other parts of Bengal. One of the branches of this business, now 175 years old, is the well-known Calcutta brand Cookme, which has done its bit to transform the Bengali kitchen over the years.

The shop set up by Krishna Chandra Dutta in Posta. The picture was clicked in the early 1930s. The Telegraph

From the Fifties, the brand has been making powdered spices, as well as pastes and ready-to-use mixes, moving away from the original business of whole spices, and the innovations, though not exclusive to this brand alone, have had a salutary effect on the kitchen.

Subhamoy, 34, who belongs to the fifth generation of the family since the start of the spice business, and runs Cookme now, tells the history of the brand modernising itself. It is also a short history of the Bengali kitchen and a glimpse into a rapidly changing society. After Krishna Chandra started the spice shop, “Keshto Duttar dokan”, as it was locally known, flourished. The business advanced when Subhamoy’s grandfather Judhisthir Dutta and his brothers took over. They began to procure spices, mainly red chillis, from outside Bengal. The shop turned into an “aaurodh (aarat)/gaddi”, a dealer’s centre. This was in the 1950s.

Then one day, at home, Judhisthir had a brainwave. “My grandfather saw how harassed his wife was, unable to give time to her family, because of her work in the kitchen,” says Subhamoy. Grinding a huge amount of spices on the stone slab was one of the most cumbersome, difficult things. He thought of a solution: ground spices, ready to use.

“At first the spices were ground manually by about 20 to 30 people on large sheel nodas (grinding stones).” The items included basic spices, turmeric, chillis, cumin. In the early 60s, the powdered spices brand was registered as Cookme. The name of the company Krishna Chandra Dutta (Spice) Pvt Ltd, of which Subhamoy is one of the four directors. The company could possibly be the first such brand in the country to make and market ground spices.

The quest to free the kitchen continued. The 70s saw another innovation: curry powder, a handy blend of spices for every curry. The 80s saw the introduction of pastes.

“Powder, blend, paste,” Subhamoy sums up Cookme’s journey. They seem to have corresponding landmarks in social history.

The kitchen changed, Subhamoy points out, radically from the 70s. The joint family broke down and the nuclear family emerged. Women began to join the workforce in larger numbers. There was far less time to spend in the kitchen, which began to convert to readymade powders.

Now these products have entered rural markets, including areas like Jangalmahal.

Hands-on at his job, Subhamoy travels to Bangalore once a month to be at the main Cookme factory, which shifted to Bangalore 27 years ago. A smaller factory is located in Cossipore in Calcutta, but there are plans to set up another near the city.

When in Bangalore, he cooks and gets a taste of his own, well, spices. When the result is not rewarding, Shubhamay sees in it an opportunity. “We have to know our shortcomings. Otherwise we don’t grow,” he says.

“Once in Bangalore, I tried to cook chilli chicken with our own ready-to-mix spices, and I realised that I needed tomato sauce, chilli sauce, soy sauce as well to prepare the dish.” That was inconvenient. On his return he asked his R&D team to come up with a mix that would not require any additional ingredient.

As always, the Cookme range aims at the Bengali palate still, but now has 40 products to its credit, from the simple turmeric, to posto paste, to two kinds of biryani masala. In between there is shukto, egg curry, chana masala, pav bhaji, tandoori chicken spices. If contemporary Bengalis show true diversity somewhere, it is their choice of food.

Subhamoy studied at Calcutta Boys’ School and The Goenka College of Commerce in the city. He is a qualified company secretary and was studying chartered accountancy. He was toying with the idea of gaining work experience outside the family business, but had to take charge of it in 2013.

“The company has always been self-funded and debt-free,” he says proudly. Though Covid has taken its toll. The one thing he cannot stress enough is the quality of his products, which never use any preservatives in the primary ground spice products, like turmeric and chilli. For some of the pastes, such as posto, which is delicate and does not last long, he uses natural preservatives. He says they are a secret, but suggests that they are not hard to guess. The brand avoids artificial preservatives.

The company is vigilant about maintaining its standards. It had discontinued its ground pepper product for two years in 2013 after it felt a pesticide using alpha toxin was being applied on the crops at a level that was not acceptable by the brand. But what about our continuous suspicion about inedible, dangerous stuff being mixed with spices as “bhejaal”? Subhamoy laughs. “You mean the hanikarak laal rang? That doesn’t really happen.”

Maybe a not-so-scrupulous brand will mix papaya seeds with peppercorns. Or, as far as chemical processes are concerned, a not-so-cautious use of oil extracted through acitone extraction process to enhance value of a ground spice. “Cookme does not use any extraction process. The spices are ground in machines,” says Subhamoy.

In any case, the future belongs to the ready-to-cook, he says. We can see its shapes already.