|

Prabhat Chakraborty stru-ggles with his memory these days, as most 95-year-olds would. But he vividly recounts going to the Hospital Ground in Chandernagore around 10am on June 19, 1949, to “vote for India”.

As the erstwhile French colony goes to the polls this Wednesday, Chakraborty will be among a handful of veterans queuing up to vote for India again, albeit in entirely different circumstances.

Back in 1949, Chandernagore had no faces to pick from. The vote was a referendum to choose nation and nationality with one simple question: “Do you want to stay with the French union (Forashi union-ey thakite chan)?”

Mrityunjoy Tosh, six years younger than Chakraborty, voted in a polling station at the Temathar More (three-point crossing) in Taldanga.

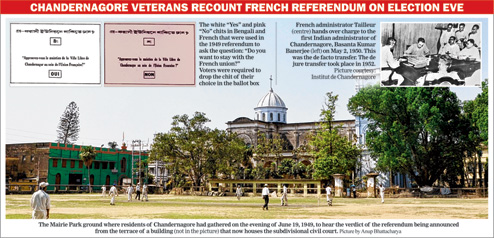

Like all voters, he was handed printed chits in two colours: white and pink. The white chit had the question along with “Yes” underneath it in Bengali and French. The pink one carried the same question with the word “No”. Voters were required to drop the chit of their choice into the ballot box.

|

The voters’ list drawn up by the French authorities had 12,115 names, of whom 7,529 participated in the referendum across 15 polling stations. Only 112 voted for France.

Records show that 4,586 registered voters didn’t turn up. Had the French included NOTA (none of the above) as an option, maybe a few more would have participated, according to old-timers in Chandernagore.

“A section of the population would have loved to stay back with the French but feared voting for it,” said Kalyan Chakrabortty.

He won’t vote on Wednesday for another reason. “I haven’t voted for many years now. Neither the government of West Bengal nor the government of India are concerned about the development of Chandernagore, contrary to what they had promised while bringing Chandernagore under the Indian Union. I don’t vote in protest,” he said.

Today, Chandernagore is an Assembly constituency with 2.05 lakh voters and part of the Hooghly Lok Sabha seat where Ratna De Nag, a doctor by profession and the sitting MP from the Trinamul Congress, is up against journalist-turned-BJP candidate Chandan Mitra. Pradip Saha, an old hand in the trade union movement, is the Left Front’s nominee for the seat.

While this election has had the contesting parties raking up issues ranging from roads to revival of closed industrial units, the epochal 1949 referendum was about making a difficult choice that many seemed happy to pass. “I don’t think the entire population of Chandernagore was very excited about the referendum,” said Hemendranath Mukhopadhyay, 99.

Chandernagore, around 30km from Calcutta, was a French settlement between 1688 and 1949. The clamour for independence from France had long been heard in the 19sqkm colony, but it got stronger after the country’s freedom from British rule in August 1947.

In his book Chandernagore: From Bondage to Freedom, historian Sailendra Nath Sen writes that the last French administrator of the colony, Tailleur, believed that “if the secrecy of the voting had been respected, the result would have been a bit different”.

Tailleur didn’t expect victory for the French but “he had not expected so overwhelming a defeat”, Sen says.

Sen, 83, also mentions that according to the neutral observers appointed to oversee the process, “the French administration had been successful in exhibiting that it had no prejudice regarding the holding of the referendum”.

The two neutral observers — Rudolfo Baron Castro from El Salvador and M. Helger Anderson from Denmark — had been appointed by the International Court of Justice.

According to Sen, a former professor of history at Calcutta University, the neutral observers found only pink slips being handed to voters in two polling booths. Around 1pm, Tailleur procured a fresh lot of white chits as the ones supplied to the two booths had been allegedly stolen.

“It proves that rigging of elections is not new to India!” quipped a young voter who has read Sen’s book.

Bimal Kumar Das, a retired railway employee, recounted why his father voted for the French. “My father felt the French were better administrators. They set up good schools here. Even during the referendum they didn’t take the school buildings, they valued education so much,” said Das, who hadn’t attained the age of voting in 1949.

“I think 21 was then the minimum age for voting,” 85-year-old Das said.

By the late 1940s, the French had realised that it would be difficult for them to retain their five colonies in India — Chandernagore, Pondicherry, Mahe, Yanaon and Karikal. Pondicherry is now a Union territory that includes the other three erstwhile French colonies contiguous to it.

Copies of leaflets distributed among voters, now stocked in the Institut de Chandernagore, tell the story of acrimony between the Congress, communist and socialist supporters, though none of these parties existed in the form and structure they do now.

The Congress Karma Parishad, mostly comprising those elected to the municipal assembly, had run a high-pitched campaign in favour of merger with India. The Left initially raised questions like why only 12,000 of the 55,000 people of Chandernagore were on the voters’ list. It made a case for “autonomy for Chandernagore” but as the date of the referendum approached, all parties appealed to the people to vote for a merger.

Chakraborty and Tosh remember microphones blaring across the colony in the run-up to the referendum. “They used to give high-voltage speeches even back then,” Chakraborty said.

The polling booths were all makeshift structures built with leaves of the Hogla tree. “Those days, they didn’t take over schools and other buildings as they do today,” said Tosh.

Hogla trees are easy to carry and their leaves can be stitched together once they are dry. Legend has it that the name Hooghly originated from the species, which once used to be found in abundance in that area.

The result of the referendum was declared the same evening from the terrace of a building on Mairie Park, barely 200 metres from the Hooghly, that used to house the luxury Hotel de Pary.

A crowd had milled on the ground in front where boys dressed in whites now play cricket for most of the year. “It was close to 9pm by the time an official appeared on the terrace to shout out the result,” Das recalled.

Chandernagore had given its verdict, though it wasn’t until four years later that the Treaty of Cession was signed.

Come Wednesday, there will be a new (and maybe harder) choice to make.

Do you know anyone/anything connected to the Chandernagore referendum?

Tell ttmetro@abpmail.com