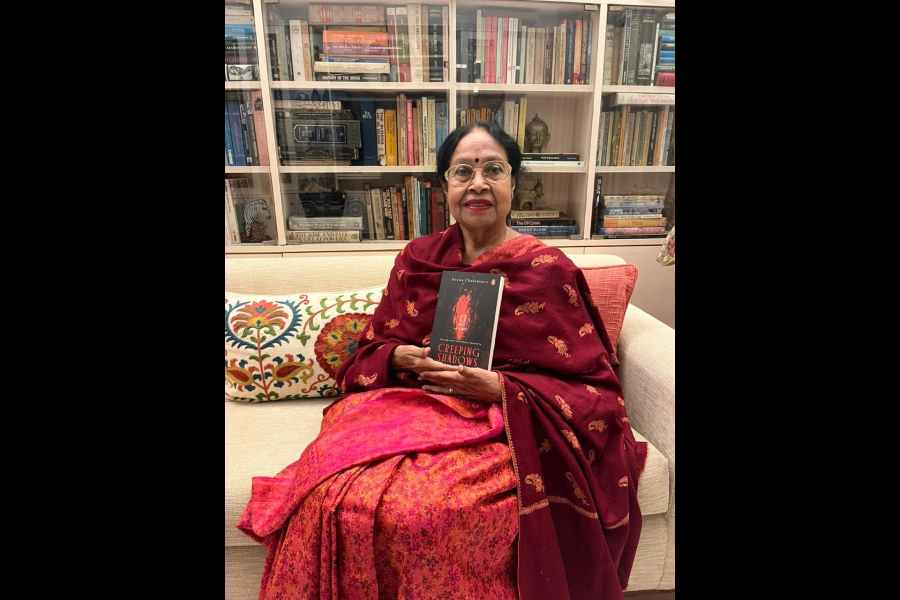

Changing gears in any profession at the age of 86 is not a choice most would select. But Aruna Chakravarti, novelist of historical fiction and translator, has, in her newest avatar, penned a collection of ghost stories. Titled Creeping Shadows: 13 Ghost Stories, published by Penguin Random House India and launched at the Kolkata Book Fair to much interest and acclaim, the genre of supernatural fiction has engaged her to veer off the academic road.

Historian by training, she has captured the imaginaire of the reading public in this new book. Chakravarti shared that she was ready for a change because she wanted to move out of the confines of research and her discipline, and she wanted to play with the idea of the supernatural. These ghost stories came out of her own mind.

Before the reader exclaims, “another ghost story!” it should be clarified that these are not the horrific, blood-and-gore exorcist-style tales, but are stories subtly told of otherworldly experiences in a literary style.

In the first story, The Caregivers of Gazipur, Chakravarti flirts with a ‘communal sutra’ and makes an important point. A starving young man, Subal, ends up being fed and cared for by Radharaman Goswami and his wife, a well-known Hindu couple. Subal learns a few days later that the couple had been dead for many years, and had converted to Islam. The author’s depiction of the converted couple as “two corpses swinging from the rafters, tongues hanging out of their mouths, eyes bulging” was a result of their being unable to live with their decision to convert.

Further, the story Vendetta deals with ecocriticism, where the husband is very different in his thinking from his wife who loves and nurtures trees. The masculinist and unevolved husband, Sudhiranjan, a botantist by profession, despises a mulberry tree in their garden, irritated by chirping birds and chattering monkeys that visit the tree, failing to realise how auspicious it is for him to have a wife, Ira, who nurtures all manner of green things. He injects poison into the tree, causing it to wither and die. Ira grows morose and detached after the death of her tree. Worried about her, he decides to take her to a forest lodge in Bankura. Will his wife recover from her sadness or will nature takes its course?

Chakravarti surprises with her novel use of literary devices that catch the attention of the attentive reader. The author’s contribution to the supernatural genre is her ability to turn the ordinary into extraordinary in the same way as Edgar Allen Poe or Alfred Hitchcock.

What is the source of her stories? Chakravarti claims they came naturally to her, and the story unfolded in her mind. There is an abundance of detail that pins her stories to geographical and historical contexts, and this strong underpinning of plot and character into reality is clearly seen in the third story, The House of Flowers. So, when the supernatural appears, it does serve as a jolting moment and makes the reader leap in surprise.

This story traces the roots of the family of the Chinese matriarch, Madame Wu, who currently lives in Calcutta. It holds tightly in its heart the secret of Madame Wu’s now very old relative, Zihan. The terrifying encounter of the protagonist, Zihan, with a beautiful but violent prostitute’s ghost decades ago in the brothel, The House of Flowers, literally makes him run as far away as possible. Chakravarti’s capturing the entrepreneurial spirit of the young Chinese migrant, Zihan, is a mastery of characterisation, and allows the reader to be a part of the story.

Chakravarti has used her time as an academic to enrich her writing. She says, “Apart from what one reads in order to teach, one also reads books of one’s choice. I have always been interested in history and read a lot, pure history as well as historical novels both in English and Bengali. So, most of my novels are set in the past. I don’t see any contradiction between the two. Teaching English Literature, which also needs an understanding of the time in which specific books were written, and writing historical novels are activities that complement each other.”

In addition, she pays close attention to the genre of the short story by ensuring that each of them is true to the genre’s “twist in the tale”. Stories such as The Necklace and Grandmother’s Bundle are remarkably well crafted with a strong showcasing of the art of juxtaposing reality bites with the ephemeral but terrifying supernatural.

The story that stands out in Creeping Shadows perhaps more than any other is One Winter Night, where a very smart storyteller weaves the socially decrepit and tortured Dalit community and the moneyed zamindars, to bring a voice of dissent to what began as a description of a “dark and stormy night”. A simple narrative of a doctor visiting a plague-ridden untouchable’s home turns into a nightmare when he discovers that this is no sick woman but a ghost. The author’s opulent table in One Winter Night, laden with haleem, khasta rotis, kormas, dals, sabzis, and mithai is in strong contrast with the open sewers and the near-starving Dalit couple in their broken-down home. You can take the historian from the archive to the supernatural zone but you can’t take away her strong consciousness of injustice.

The principal of a Delhi University college for 10 years, an administrator, a writer of 17 published books, five of which are novels, she is also the recipient of awards for her creative writing. The author has shown great scholarship and writing skills in creating sagas. Historian Carlo Ginzburg maintains in his study History, Rhetoric and Proof: “The idea that historians should or can prove anything seems an antiquated idea to many, if not downright ridiculous. I want to demonstrate in the past that proof was considered an integral part of the rhetoric.”

Dalit literature has been hitting the global headlines with Chakravarti’s new book on Dalit Literature, Rising from the Dust (2025) — in which the author translated stories written by Dalit women in Bengali — being a part of the trend. What was it like to move to translating Dalit voices from Bengali to English? “It was a totally different experience. Moving from creative writing to translation has always been a refreshing change for me. Since my novels are all research-based and carry with them the usual load of anxiety and tension regarding historical and social authenticity, I tend to go back to translation every now and then,” shared Chakravarti before signing off.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is the author of Dance of Life, and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College. She curates and anchors the Rising Asia Literary Circle and is the t2 literary columnist.