|

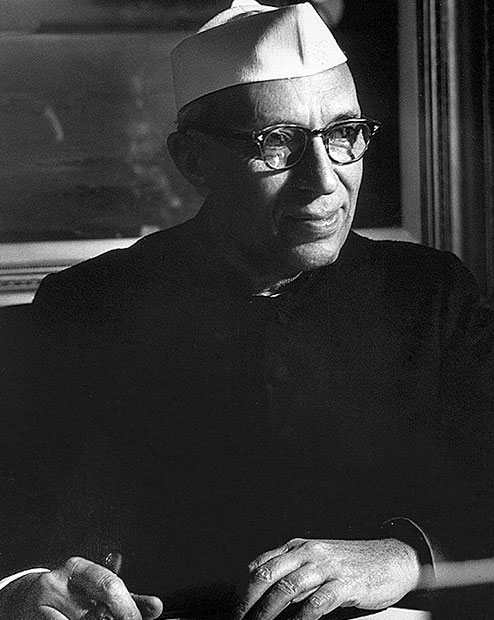

Letters for a Nation: From Jawaharlal Nehru to his Chief Ministers 1947-63 Edited by Madhav Khosla, Penguin, Rs 599

As Nehru’s India unravels post-May 2014, it is most apposite that Madhav Khosla should anthologize Nehru’s fortnightly letters to his chief ministers over sixteen of the seventeen years of his premiership to remind us of the India he raveled, which clumsy hands are now attempting to dismantle. It is like securing a ringside seat at the building of modern post-Independence India: the sweep and detail of the philosophy that went into it; the topical issues that arose and were tackled within the framework of a deeply compassionate and ethical approach to problem-solving; and the fashioning of institutions which would constitute the infrastructure that has made us the only sustained democracy of the 150 or so nations that came to liberation of one form or the other in the years following 1947. We would not have been what we became — a democratic, secular, socialist and Non-aligned republic — but for Nehru. In the face of the immense challenge of an RSS-run India that we are now in danger of, Khosla’s is a useful reminder of the values and Weltanschauung (world-view) that went into the making of pre-Modi India — indeed, the very Idea of India — that is now under siege.

Nehru’s correspondence with his chief ministers has, of course, been compiled by the noted historian, Dr S. Gopal, decades ago. Why then an anthology now? My own reason is that the Gopal version was chronological — it told the story from fortnight to fortnight. This compilation is thematic — it compiles the letters in five broad categories — “citizenship, democratic institutions, national planning and development, war and peace, and the international order”. Why would chief ministers want, or need, to know about these matters, many of which were and, alas, are far removed from their daily concerns? Khosla cites a fictional but typical home minister invented by the novelist, Vikram Seth, asking, “Why these long homilies about Korea and the dismissal of General MacArthur. What is Gen MacArthur to us?” And goes on: “He doesn’t have the least idea of administration but he talks about the kind of food committees we should set up.” Inadvertently, that reveals the range of issues covered in the fortnightly letters — ranging across the world and spanning the spectrum from the abstruse to the mundane.

For that is what made the man. He thought laterally, linking apparently tangential matters into a coherent picture that placed the immediate in the context of the larger and the longer perspective and lent broader meaning to diurnal administration than the disposal of dusty files. (I recall H.Y. Sharada Prasad remarking of Robert Frost’s poem found on Nehru’s bedside when he died that it should have read, “And files to go before I sleep/And files to go before I sleep!”) For Nehru, the drama of the making of the modern India was part of the saga of the making of modern Man and the Indian was part of a global family. He titled his own Azad Memorial lecture, “India and the World”.

Khosla adduces several other reasons for the present anthology. First, the continuing need for an “understanding” of Nehru’s ideas, that is, “Nehru’s effort at creating norms for the exercise of public power to fortify the fragility he saw inherent in any political experiment”; second, “for the historical record they provide... Nehru showed nation-building to be a prosaic affair demanding infinite patience, one whose processes and institutions could only endure through cumulative acts of consolidation. Making (Khosla’s italics) a nation, rather than merely administering it”, including the challenges that the “unchallenged Nehru” faced, both from within his party and from outside; and, third, because these themes “confront dilemmas that resemble those of contemporary India”.

And this is how Khosla explains his grouping the letters into five broad themes. On “Citizenship”, he says, “Nehru was attentive to the dangers of communal politics and an exclusionary brand of nationalism. The politics of particular identities — whether religious, caste or linguistic — stoked fear and resentment, and no society could sustain (itself) if a segment of its people felt alienated”. Therefore, Khosla concludes, “Nehru kept a close watch on (communal) activities, maintaining throughout that communalism was among the greatest threats to India”. It still is, especially now that the possibility of State-sponsored communalism, as in Gujarat 2002, is an ever-present threat.

On the “Institutions of Democracy”, Khosla stresses Nehru’s emphasis on “associating democratic rule with strict vigilance over the instruments of law and order”; “public reasoning and justification as central to democratic participation”; and the danger to democracy of “corruption, nepotism and a general weakening of the moral fibre”. The crushing defeats of the UPA in May 2104 and in the subsequent state elections are proof, if proof were indeed needed, of how the ink stain on the reputation of a government will remain at least till the next election.

The third theme is “National Planning and Development”, a theme peculiarly relevant to the present with Modi’s mindless decision to abolish the Planning Commission without thinking through what he is going to put in its place. Khosla describes planning as lying “at the heart of Nehru’s effort to marry a welfare state with democracy”; the need for “a scientific and rationalist approach towards government policy”; and the imperative for the public sector to occupy “fields of strategic importance”. All this is being abandoned as the Modi government succumbs to the AAP — not the Aam Aadmi Party, but the Ambani Adani Party. Equity, environment and a fair deal for labour are being thrown overboard and social justice made dependent on CSR crumbs. Equally, Panchayati Raj — the predominant preoccupation of Nehru through the last seven years of his life — are being given a miss-in-the-baulk by the current establishment, thus undermining grassroots democracy and participative development.

Finally, the intertwined themes of “War and Peace” and the “International Order” need invocation at a time when the prime minister talks of “goli” not “boli” and the defence minister threatens a “jaw-breaking” reply (munh-thod jawab).

I have not quoted from the letters themselves as I do not want to deprive the reader of the sheer “charm” of these letters. To read these is to be “Present at the Creation”.