One of the joys of reading old newspapers on microfilm is the serendipitous discoveries one makes. Looking for reports on Gandhi’s stay in Calcutta in August-September 1947, I came across a remarkable letter written by an unknown Indian. His name was M.S. Ali, he lived in Dum Dum, and his letter, published in The Statesman on August 12, 1947, read as follows: “Sir, — Pakistan State will consist of five provinces — each of which has a distinct language of its own. Of these Bengali is most advanced, its vocabulary is rich and flexible, compared with it the others are poor languages.

“Urdu, though highly advanced and rich, is not a language of the masses of India or of Pakistan. Its use is confined to the educated north-west Indian Muslims. It should not therefore be made Pakistan’s State language, far less, the medium of instruction in the Pakistan universities. If a foreign language, European or Indian, is thrust upon Pakistan’s provinces, a set of people speaking that language will get the upper hand over others. This will greatly hamper the progress of Pakistan as a whole.

“I suggest that each of the five provinces should have a board of specialists in different languages and this board should be put in charge of inter-provincial correspondence and other inter-connected matters. This would solve the linguistic difficulties. The Centre, like the provinces, should also have a board of its own and thereby avoid adoption of any particular language as its own. If a particular language is at all necessary for the Central Government I suggest the use of English.”

The writer was a Bengali-speaking Muslim, who perhaps sought to move to the east of the province once it became part of Pakistan. Yet his letter did not merely express a parochial Bengali sentiment. Ali knew that the other provinces of the soon-to-be-formed state of Pakistan also had their own dominant language, which in each case was not Urdu. The residents of Punjab principally spoke Punjabi, the residents of Sind principally spoke Sindhi, the residents of the North West Frontier Province largely spoke Pashto and the residents of Balochistan largely spoke Baloch. He thus asked for each of these languages to be respected and promoted. And he asked further that a language utterly foreign to the majority of citizens of a future Pakistan, namely Urdu, not be imposed on them.

The sentiments were admirable and far-sighted, but the founder of Pakistan was not listening. Muhammad Ali Jinnah was determined that the state he was bringing into being would privilege one religion and one language alone. Here, Jinnah was deeply influenced by Western models of nation-making, wherein residents of a particular territory had been forcibly brought together and united on the basis of a shared language and a common religion. On the other hand, Jinnah’s great rival and contemporary, M.K. Gandhi, had chosen an altogether different model of nation-making, which respected diversity and difference, and refused to identify citizenship with a single language or a single religion.

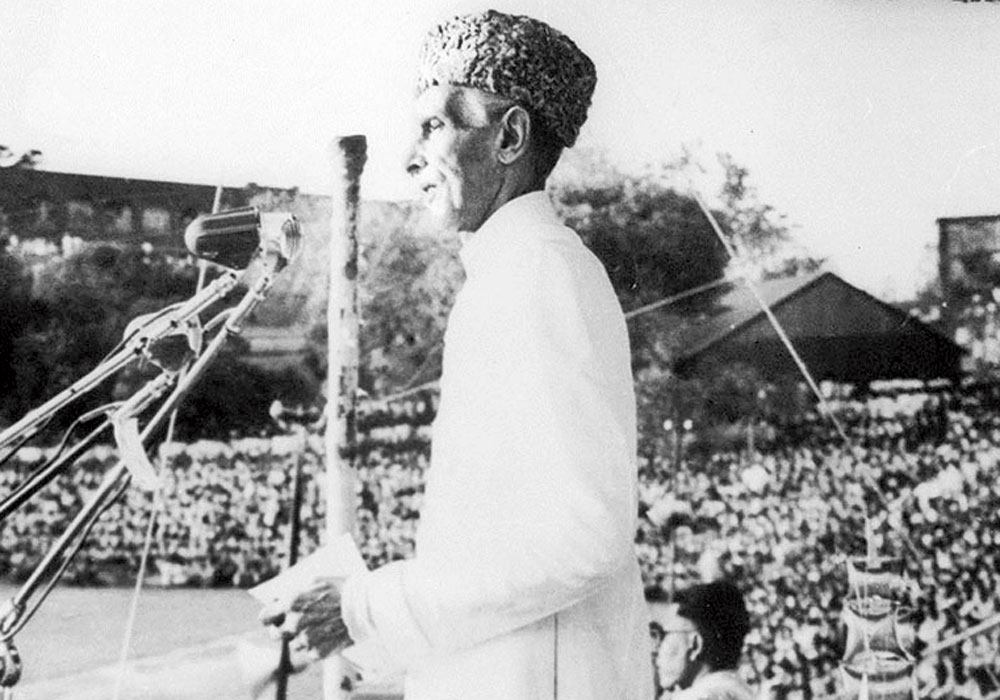

Six months after Pakistan was created, its governor-general visited the eastern part of the nation. In a major speech in Dhaka on March 21, 1948, Jinnah said: “There has also lately been a certain amount of excitement over the question whether Bengali or Urdu shall be the state language of this province and of Pakistan. In this latter connection, I hear that some discreditable attempts have been made by political opportunists to make a tool of students in Dacca to embarrass the administration.”

Then Jinnah continued: “Let me warn you in the clearest terms of the dangers that still face Pakistan and your province in particular, as I have done already. Having failed to prevent the establishment of Pakistan, thwarted and frustrated by failure, the enemies of Pakistan have now turned their attention to disrupt[ing] the state by creating a split amongst the Muslims of Pakistan. These attempts have taken the shape principally of encouraging provincialism.”

Speaking further on the question of language, Jinnah remarked: “Whether Bengali should be the official language of this province is a matter for the elected representatives of the people of this province to decide. I have no doubt that this question should be decided solely in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants of this province at the appropriate time. Let me tell you in clearest language that there is no truth [in rumors] that your normal life is to be touched or disturbed, so far as your Bengali language is concerned. But ultimately it is for you, the people of this province, to decide what should be the language of your province.”

This seemed to be a concession to the depth of provincial sentiment, an appreciation of what their language meant to the Bengalis. However, Jinnah continued: “But let me make it clear to you that the state language of Pakistan is going to be Urdu and no other language. Anyone who tries to mislead [you] is merely the enemy of Pakistan. Without one state language, no nation can remain tied up solidly together and function. Look at the history of other countries. There[fore] so far as the state language is concerned, Pakistan’s language should be Urdu.”

So, in Jinnah’s Pakistan, Bengali would be subordinated to Urdu in such matters as education, employment, government communications, and the like. In insisting that there would be only one State language, Jinnah was exhibiting a certain paranoia. He was nervous that his newly established nation would come apart if it did not adopt certain common criteria of citizenship. Jinnah wanted to make sure that Pakistan would be a Muslim nation, and an Urdu speaking nation as well.

On the other hand, Gandhi and, following him, Nehru, adopted a more capacious idea of citizenship. Here, it was not mandatory for the State to be identified with a single religion, nor indeed for one among India’s many languages to be elevated to a paramount and superior status. India would not be a Hindu nation. Nor would Hindi be forcibly imposed on the south and the east of the country. There would be no official State language, and each province would have the freedom to promote and enhance its own linguistic traditions.

As is well known, the elevation of Urdu over Bengali was a, perhaps the, major reason for the rise of separatist sentiments in East Pakistan, which grew and intensified over the years and resulted eventually in the creation of the independent nation of Bangladesh. Jinnah had claimed: “Without one state language, no nation can remain tied up solidly together and function.” In fact, the situation was the reverse; largely because of the imposition of one State language, Pakistan could not stay together and function, and broke into two. If the founder of Pakistan had the fortune to have read M.S. Ali’s published letter, and the wisdom to implement its suggestions, Bangladesh may never have come into existence.

There is one last point I wish to make. This is that the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s idea of nationhood is, as it were, a Xerox copy of Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s. For them, to be properly Indian is to be a Hindu, and to be truly Indian is to be able to speak Hindi. While the current RSS chief speaks of the primacy of Hinduism over all Indian faiths, his epigones enact his ideas on the streets, by committing acts of violence on those who are not Hindus. Meanwhile, the Bharatiya Janata Party-led Central government slyly seeks to promote Hindi at the expense of other Indian languages. Fortunately, there are many Indians who think about their country in the manner that M.S. Ali thought about Pakistan. The majoritarianism of faith and of language shall not come to pass.