Indian politicians love to hang on to laws from the colonial era — the law against sedition is an example. Inscribed as Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, sedition is the incitement through speech or act to rebel against the authority of the government or the monarch. It made sense when there was a colonial government. The law becomes irrelevant in a democracy where the relationship between the people and their government is supposed to be different; even the United Kingdom repealed it in 2010. In a multi-party democracy that sees freedom of expression as a fundamental right, criticism and dissent are to be expected. Evidently Indian politicians feel too insecure to let go of old, repressive laws. They cannot let the law against sedition go in spite of having formulated such laws as the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, for example, against alleged ‘offences against the State’. Data under this head in the latest National Crime Records Bureau report show that although the number of cases under sedition has risen through the last few years, the conviction rate has fallen sharply, especially in comparison with the cases under the UAPA. Among cases heard, two people were convicted of sedition in 2019 and two in 2018, while 29 and 21 people were acquitted respectively each year. Yet 93 cases of sedition were filed in 2019, although 70 in 2018, and 56 in 2017.

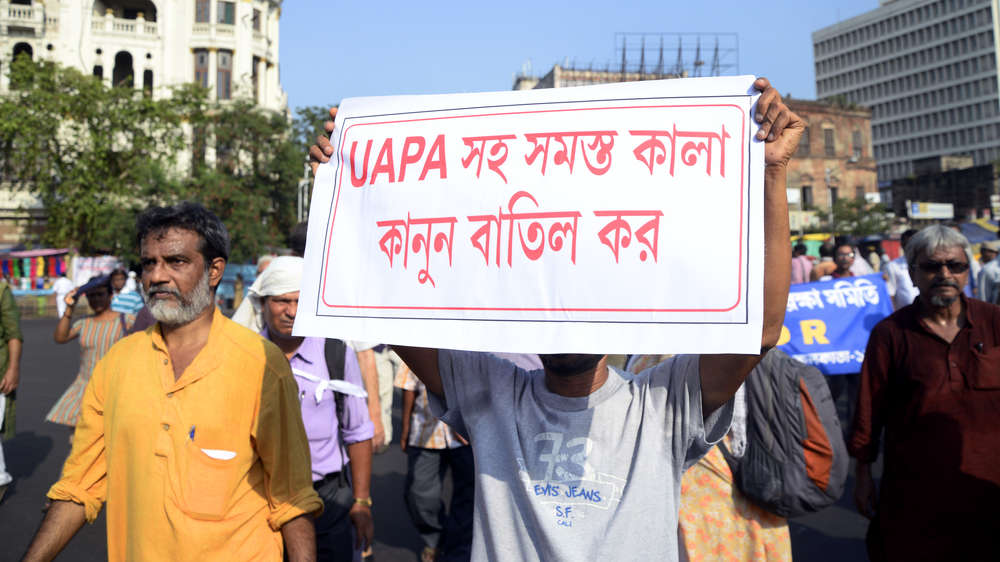

The story behind the data is a comment on the attitude of the Bharatiya Janata Party-led government at the Centre that is reflected also in the culture of BJP-ruled states. The law against sedition is simply one weapon in an arsenal to silence dissent: the Jharkhand chief minister, for instance, ordered 3,000 charges of sedition against anti-Citizenship (Amendment) Act protestors to be dropped. Recommendations to repeal the law have been ignored; the present government says it is needed to combat “anti-national, secessionist and terrorist” elements. But it is one thing to file a sedition case, quite another to prove it. It is not a question of bundling out foreign rulers or a king. This is a democracy where freedom of expression is the people’s fundamental right. The NCRB data on poor conviction rate in sedition cases would be comic had not the reason behind the cases been so grim.