The oft-repeated truism that universities serve as society’s moral compass assumes a particular resonance in the Indian context where the very guardians of conscience are being incrementally stifled by a system of appointments mired in partisan machinations. Consequently, the sacrosanct principles of intellectual rigour and academic excellence are being systematically subordinated to the dictates of political expediency. Mediocrity, it is widely observed, is often rewarded while merit is the casualty.

At the crux of this pedagogical malaise lies a disquieting conundrum. Why do our institutions of higher learning remain in the grip of political appointees?

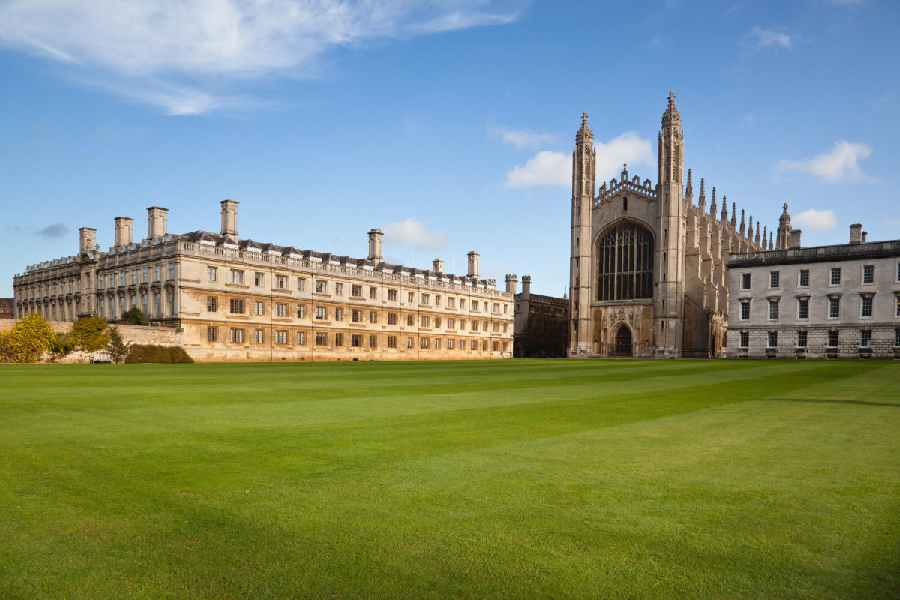

Just the other day, my wife cast her vote as an alumna of Cambridge University for the election of its chancellor. It wasn’t just a ceremonial act; it was a moment of quiet dignity, a reaffirmation of the idea that even the oldest institutions in the world thrive when they trust their community to shape their future. The vision write-up of the 10 shortlisted candidates was sent to every voter to decide who was the most deserving. The process spanned several months, involved rigorous vetting, open nomination, and concluded with a democratic vote by alumni across the globe.

Lord Smith, the first openly gay British MP and a long-standing advocate for the arts, culture, and education, was chosen not for political utility but for his alignment with the values he wishes to uphold — integrity, intellectual freedom, and commitment to public life. He exemplifies a symbiotic convergence of scholarship, civic engagement and unwavering fortitude, a testament to the institution’s enduring commitment to intellectual freedom, university autonomy, and the ethico-moral imperatives that undergird the academic initiative.

This set me thinking how vastly different, how deeply disconcerting, the contrast is with the appointments of chancellors and, more crucially, of vice-chancellors in India. This seemingly mundane act of alumni voting encapsulates what we in India have so tragically lost in the sphere of higher education, particularly institutional trust, participatory governance, and respect for scholarship. Unlike Cambridge or Oxford, Indian universities remain mired in a system where appointments are shrouded in secrecy, dictated by political whims, and executed through bureaucratic edicts.

In this peculiar institutional arrangement, the governor of a state assumes a dual role, serving not only as the ceremonial head of the state but also as the chancellor of all public universities within its jurisdiction, notwithstanding the fact that the blending of executive power with academic decision-making stands outdated as a practice and is problematic. This approach, inherited from the colonial past, allows politics to overly influence universities, undermining their integrity and purpose. In stark contrast to valued institutions like Cambridge, our university heads are often chosen through backroom negotiations, frequently influenced by politically-motivated committees or, more alarmingly, unilaterally appointed by the chancellor-governor. This process is devoid of alumni participation, academic input, or public discourse, leaving the university community to acquiesce in silence.

In numerous instances, these university heads function not as custodians of academic integrity but as partisan emissaries, insidiously influencing faculty appointments, obstructing selection processes, and leveraging their authority to either impede or facilitate candidates based on their usefulness to the ruling establishment. This phenomenon transcends mere procedural irregularity; it constitutes, instead, a profound structural dereliction. The appointment process for this pivotal position is characterised by arbitrariness, thereby imperilling the very foundations of the university. The incumbent’s job is not to lead intellectually but to manage politically.

In India, the very idea that alumni across the world could vote would be laughed out of the room. Understandably, the liberatory ethos of education is now subordinated to a narrow desire for control by those who evidently fear the unbridled pursuit of knowledge and critical scrutiny. We are witnessing a regressive transformation in institutional architecture wherein gubernatorial fiat, bureaucratic intrigues, and partisan loyalty dictate the contours of academic life. In such a scenario, the university’s autonomy and institutional integrity suffer a de facto erosion.

India must catch up. At the very least, it must end the colonial-era absurdity of governance. The University Grants Commission or its successor must push for independent selection committees for vice-chancellors comprising academics of repute drawn from across disciplines and regions. The time has come to restore faith in intellect, not just the institution. Search committees must be constituted keeping in view the fact that the intellectual culture of a university is profoundly shaped by the disciplinary background of its leadership. When vice-chancellors emerge not only from the sciences but also from the liberal arts and liberal sciences where scholars are trained to read critically, think historically, and engage ethically with ideas, the institution invariably registers a richer academic life where seminars flourish, conferences multiply, and the campus becomes a space of conversation rather than bureaucratic silence.

One only has to look at figures such as the present chancellor of Cambridge whose doctorate in English literature on Wordsworth, no less, equips him with a sensitivity to ideas, culture, and human complexity that is indispensable for stewardship of the academy. Contrast this with the distressingly common phenomenon of vice-chancellors who have scarcely opened a novel or a poem and for whom literature and the humanities are a peripheral indulgence rather than the heartbeat of intellectual formation. When universities are led by people untouched by the humanities, the result is governance without imagination and administration without vision.

This is why the example of Cambridge and, yes, even Oxford, matters. Here, the chancellor, while largely symbolic, is not imposed. And the vice-chancellor, the real executive head, is chosen after global searches, peer evaluations, and rigorous scrutiny. India must reclaim this principle. First, the appointment of vice-chancellors must be handed over to independent search committees composed of distinguished academics with inputs from faculty and students. These committees must function transparently, publish shortlists, and justify their recommendations. Second, alumni must be re-engaged, not just for donations but for decisions. Why shouldn’t retired professors, emeritus scholars, and even current faculty be part of the conversation?

The imperative to address this issue cannot be overstated. Universities transcend their role as mere pedagogical institutions, functioning instead as vital repositories of democratic values and civic culture. When administrative leadership is determined by partisan allegiance, the future of India’s intellectual trajectory hangs precariously in the balance. The nation is thus compelled to make a paradigmatic choice of whether to relegate universities to the status of adjuncts to the prevailing political apparatus, or to preserve them as autonomous bastions of intellectual inquiry. Only one of these alternatives aligns with the foundational promise of a republic wherein the pursuit of knowledge and critical thought is paramount. The stakes are clear. The fate of India’s intellectual life and, by extension, its democratic polity remains at a crossroads.

Shelley Walia is a cultural critic and former Senior Fellow at the Rothermere American Institute, University of Oxford