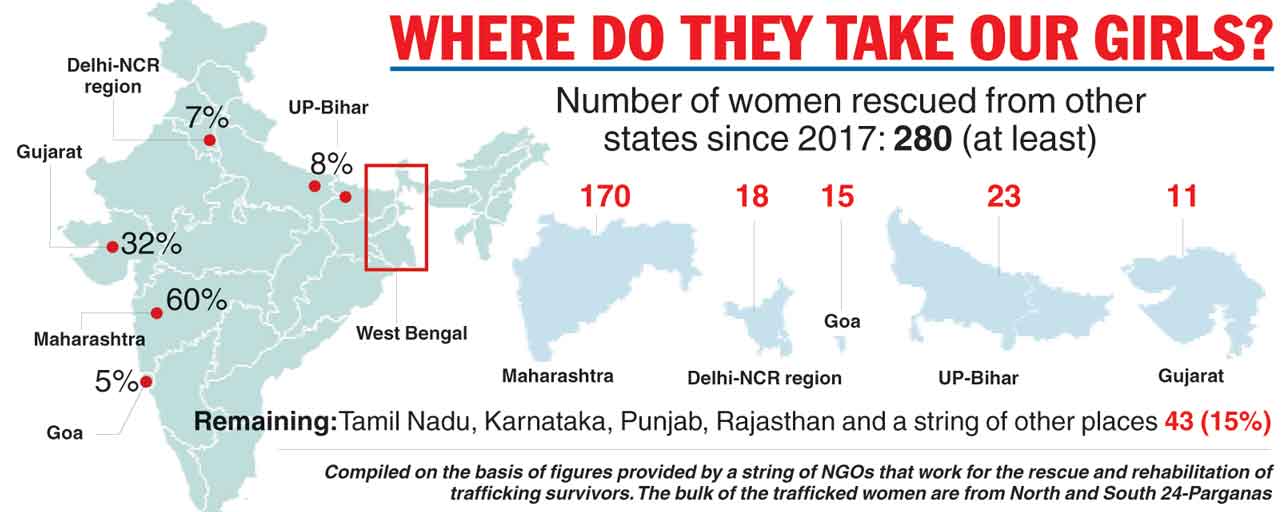

Women from south Bengal are trafficked to destinations across India.

But six out of 10 land up in Maharashtra.

Pune is the single largest destination for them. Delhi and surrounding areas, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Goa also account for a good number of trafficked women from Bengal.

According to inputs from a string of social organisations that work for the rescue and rehabilitation of trafficking survivors, at least 280 women from south Bengal have been rescued from other states since 2017 (see graphic).

Many of them were children and most were from South and North 24-Parganas, two neighbouring districts of Kolkata.

Over the years, figures from the National Crime Records Bureau have suggested that Bengal is one of the largest source markets for traffickers. An officer of the state CID said the trafficking complaints had come down in 2020 because of the Covid-induced curbs on train services.

“As soon as full-scale train services resume, the numbers will go up again,” he said.

Places

Sixty per cent of the rescues were from brothels in the red-light district in Pune’s Budhwar Peth, according to the figures shared by NGOs in Bengal. The infamous address is home to around 3,000 sex workers.

Social workers outside Bengal, who are often part of the rescue operations with the local police, also corroborated their Bengal counterparts. “In the past four years, we have rescued over 100 women from Bengal from Maharashtra. The majority of them were from Pune,” said Rajesh Chaturvedi of Mission Rescue Foundation, based in Mumbai.

“The survivors from Budhwar Peth have given horrific accounts of the place. The physical assault is often more brutal during the first few weeks because the traffickers want to absolutely crush the girls’ spirits,” said Sambhu Nanda of Partners in Anti-Trafficking, a network of survivor groups in North 24-Parganas.

But in many other cities, like Mumbai, Gurgaon and Delhi, the survivors were not rescued from red-light areas but from hotels and private properties, said activists.

In the heartland, in places like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, the profile of the traffickers is different, said police and NGOs.

The women are trafficked on the pretext of a job in dance troupes.

“In many cases, we have found that the parents or guardians of a girl knew she was being taken to work in a dance troupe,” said a police officer in the anti-human trafficking unit of Bengal police.

Traffickers

Between home and a trafficker’s den, a girl goes through several hands. The first person to lure her is a familiar face — relative, neighbour, friend and their likes — in most cases.

The first stop for most survivors is a train station. A spiked drink or meal has been the undoing of many.

“The traffickers prefer general compartments of trains. The overcrowded bogies are more suited to their schemes than reserved coaches, which are inspected by railway cops and ticket inspectors regularly,” said Amina Laskar, a member of Bansra Birangana Seba Samiti, another South 24-Parganas-based organisation.

Aides of traffickers often spend hours outside phone recharge stores, trying to get access to the log book. An innocuous missed call or a random friendship message is often the starting point of an operation that lands minor girls in outstation brothels, said police and rights activists.

But in most rescue cases, the kingpin is not arrested. A detailed probe would entail a trip by the local police to the place of rescue. The police often lack the resources to go to another state, alleged activists.

“The masterminds stay behind the curtains. Local aides get arrested and get bail, only to resume the same work,” said Subhasree Raptan of Goranbose Gram Bikas Kendra, an organisation

that works with many trafficking survivors in South 24-Parganas.

Survivors

Accounts from survivors and social helpers revealed different ways in which the traffickers operate.

nA 14-year-old girl from Canning left her home after a feud with her parents in 2014. She was headed to a relative’s place in a van where a woman befriended her. The van never took her to the relative’s house. It went to the station instead. The girl was kept at a hotel near the NRS Medical College and Hospital in Sealdah for a few days before being trafficked to Pune.

nIn 2018, a woman from the southern fringes of Kolkata, awaiting her BCom results, left home for a trip to Goa with friends. She ended up at the hands of traffickers who exploited her for many months. She was rescued from a hotel in Goa.

“The traffickers play the bait according to the profile of the target. Many of the survivors are from very poor families. They are lured with the promise of a job. Some fall for the false promise of love, marriage and freedom. The traffickers are always alert and pounce on the slightest chance,” said Raptan.

A natural calamity, like a cyclone, which puts enormous pressure on livelihood, makes the situation worse.

Hundreds of women from North and South 24-Parganas were trafficked in the aftermath of cyclone Aila in 2009.

The same areas were devastated by the Amphan in 2020 and Yaas in 2021, both in the backdrop of a raging pandemic.

A conclusive report on the surge in trafficking or missing reports in the aftermath of these storms is yet to come. But activists fear the traffickers already have many vulnerable girls under their wings.

This newspaper had reported multiple times on a spike in child marriages, often the first step towards being trafficked.