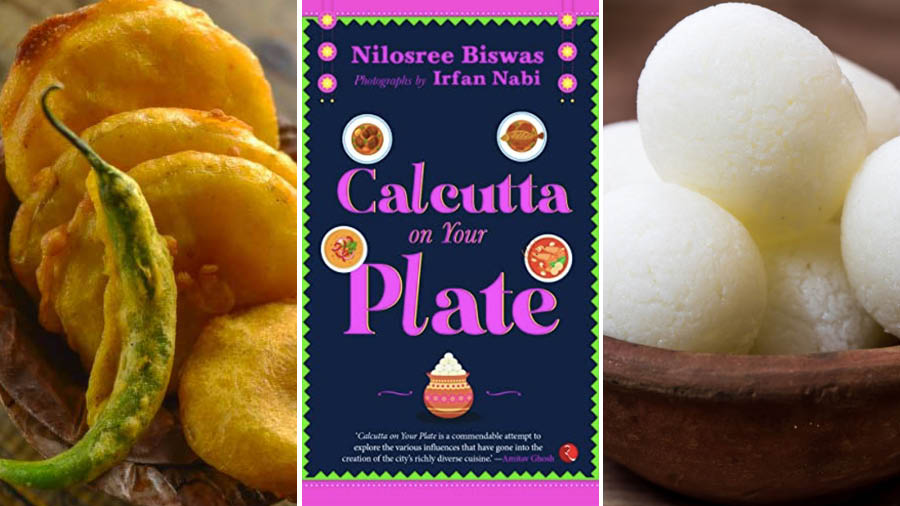

In Calcutta on Your Plate, Nilosree Biswas explores the richness of Kolkata’s palate by unearthing stories about its most popular food items as well as some of its most obscure ones. In an excerpt from the book, which can be purchased here, Nilosree offers a slice of the history and heritage behind some of Kolkata’s most prominent sweetmakers and their memorable creations.

The Portuguese who could not resist Bengali sweets

The Portuguese traveller and monk Fray Sebastien Manrique, travelling from Bengal to the Punjab in the 1630s, noted that the Bengalis had “many kinds of lecteus [lacteous] food and sweetmeats prepared in their own way, for they have great abundance of sugar in those parts”. The good Manrique may well have succumbed to the temptation, for he reports: “Entire streets could be seen wholly occupied by skilled sweetmeat makers, who proved their skill by offering wonderful sweet scented daunties (sic) of all kinds which would stimulate the most jaded appetite to gluttony.”

Riding on this legacy emerged today’s heritage confectioners — the sandesh specialists Bhim Chandra Nag, Girish Chandra Dey and Nakur Chandra Nandy, KC Das (Nobin Chandra Das’s family brand), Nabakrishna Guin, Sen Mahasay and Putiram, all starting out in the decades of the 19th century, a time when Calcutta was gloriously cosmopolitan with ample opportunities for innovators. Thrilling things happened in the world of sweetmeats in the next few years.

Soon, Krishna Chandra Das, popular in present times as KC Das, set up his manufacturing unit KC Das and Co. He had by then invented the second-most memorable sweetmeat from his stable—the delicate rasmalai, which resembled patties made of chhana and was soaked in sweetened milk.

Many products were developed by enterprising moiras: Kheer Mohan and cham-cham, mouchak (shaped like a beehive), sitabhog, resembling rice grains, gulab jamun, lal mohan, totapuri, among others. Pantua and chitrakoot are again chhana based and in Bengal even the jalebi is termed Chhanar Jilipi and deploys chhana to create whorls that are deep fried before being placed in syrup.

Ramakrishna had standing instructions for his closest disciples to fetch him ‘sandesh’

Like so many others, Ramakrishna Paramhansa was a big fan of ‘sandesh’ Irfan Nabi

Started by Param Chandra Nag in 1826 and inherited by his son Bhim Chandra Nag, the present-day sandesh of Kolkata is synonymous with the Nags. The sandesh, simple in its form and look, took birth at their Bowbazar Street shop. Unassumingly called Makha Sandesh (mashed and hand-pounded), it was an accidental creation, a well-meaning thought to prevent the wastage of chhana. With no refrigeration and soaring temperatures, particularly in the summer, a large volume of chhana had to be discarded by the end of the day. The innovative confectioner came up with the idea of adding ground cardamom, sugar and khoa to increase its shelf life. The final shapes could be anything, from simple rounds like kanchagolla to something that is disc shaped.

After that, there was no looking back. Perhaps, it was divine interplay between the celestial and human agencies that Bengali sweets rolled on their golden journey. In consolidating its massive outreach, patrons like Rani Rashmoni, a renowned philanthropist of her times, played a major role. Rashmoni founded a Kali temple at Dakshineswar, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly, in 1855. She ordered 28 maunds of sandesh on the day the temple was inaugurated. Her chief priest, popular religious leader Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, better known as Vivekananda’s spiritual mentor, was another important connoisseur of the sandesh.

In love with what food historian Michael Krondl describes as the “haiku” of sweets, Ramakrishna had standing instructions for his closest disciples to fetch him sandesh whenever they would visit him. In fact, Nobin Chandra Das’s Dedo Sandesh was dedicated to Sarada Devi, the wife and spiritual consort of Ramakrishna.

The Bengali intelligentsia, too, wholeheartedly supported enterprising confectioners. Rabindranath Tagore was fond of Nobin Moira’s rosogolla, as was Ashutosh Mukherjee, the then vice chancellor of Calcutta University. The pioneer confectioner created a special sandesh named Ashubhog, dedicating it to his doting patron. The legend goes that Ashutosh’s buggy would stop at Bhim Nag’s every morning on its way to Calcutta University and Bhim Nag himself would keep his daily parcel of sweetmeats ready.

From Lady Canning to ‘ledikeni’

‘Ledikeni’ has a number of stories to explain its origin, but two tales have become more popular than others TT archives

Abar Khabo, which Mukherjee is known to have gorged on, is a delectably indulgent sandesh that Nobin Chandra Das created especially for Maharani Swarnamoyee Devi of Cossimbazar, who apparently had got bored of the existing repertoire of sweetmeats. Ledikeni (the alternate spelling of Lady Canning), on the other hand, was a dedication to the vicereine, the wife of Viceroy and Governor General Charles Canning. Conceived by Bhim Nag, ledikeni—an oblong, golden-brown, deep-fried sweetmeat stuffed with raisins and cardamom powder—is a variant of the Bengali pantua (deep-fried balls of semolina, chhana and sugar syrup). Shrouded with fascinating versions of stories, ledikeni is remembered by almost all in Calcutta. The most popular version has Charles Canning wanting to gift his wife a special dessert on her birthday and asking the prominent confectioner to make one exclusively for the occasion, leading to the birth of ledikeni.

Another version is how a motley group of confectioners from Behrampore, Murshidabad created the sweetmeat to commemorate Lady Canning’s visit to India in 1858. Whatever is the more authentic version of the anecdote, the first lady loved the confection. After her demise, the popularity of the sweet grew remarkably.

In 1858, Robert Thomas Cooke of Cooke and Kelvey (C&K), British India’s most sought-after silverware and timepiece maker, known for their finest Swiss movements, happened to visit Bhim Nag’s Bowbazar shop. Delighted by the sweet allure of Nag’s creations, Cooke wanted to gift Nag a clock, which was surprisingly missing in his outlet. Nag then requested for Bengali numericals on the clock, so that his karigars (workers) could sense the time. Cooke obliged, and till date, the heritage timepiece adorns the wall of Bhim Nag’s Bowbazar outlet…

A sandesh was named after Lord Ripon, Viceroy from 1880 to 1884. In the 1960s, a sandesh was called Bulganiner Bishmoy (Bulganin’s wonder), honouring the Soviet premier Nikolai Bulganin’s visit to the city. Perhaps such nomenclatures were conscious acts, strategies to find a place within the closed-door elite society of Calcutta. Eventually, entrepreneurial grit of this nature compelled a shift in the social positioning of moiras, resulting in their movement up the social ladder.