The iconic poster of the 1957 epic melodrama Mother India that shows a deeply distressed Nargis carrying a plough on her bare shoulder was meant to challenge American author Katherine Mayo’s 1927 book of the same name, which was putatively a smear campaign against old India. In a somewhat similar manner, the exhibition

at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), Mumbai, that opened on December 12, attempts to shift the axis of ancient world history from Egypt and later Greece to the Harappan (Indus Valley) civilisation, which is represented here by Dholavira — one of its settlements in the Rann of Kutch, Gujarat.

The brilliantly conceived and displayed exhibition is called Networks of the Past: A Study Gallery of India and the Ancient World, and it will be on for three years.

By devoting an entire section to farming, this exhibition argues that the humble plough had powered the flowering of civilisations. This rereading of history is brought alive by more than 300 workaday as well as exquisite original archaeological objects ennobled by their antiquity from the river civilisations of India, Egypt, Mesopotamia and China, which came later, and expanding into the Persian, Greek and Roman worlds (from around 4000 BCE to 400 CE).

These objects are from six international and eight Indian museums, including the CSMVS. Instead of presenting a grand spectacle, viewers may feel they have gained an insight into the lives of people like us, the gulf of time notwithstanding. The maximum number of objects, 85, came from the British Museum, London, followed by 70 from the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

In another first, this exhibition was co-curated by the CSMVS staff as well as curators from London, Berlin, Zurich and Athens. According to the project statement, it involved a series of conversations over three years. Neil MacGregor, adviser to Getty, and Mahrukh Tarapor, international museum expert, worked as consultants. “Trust played a profound role” in furthering collaboration, said Tarapor. Getty and CITI are major donors.

“We were completely independent in selecting objects and developing the narrative. Both the Union and Maharashtra governments were supportive... The exhibition, like the museum, is totally supported by public-private partnership,” says Sabyasachi Mukherjee, who has been director general of the CSMVS since 2007.

The rotunda of the CSMVS, where a model of Dholavira (3000 to 1500 BCE), a key Harappan site, leads to the new learning gallery Networks of the Past. Courtesy: Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), Mumbai

The CSMVS’s aim is to take culture to doorsteps, even in rural areas. A project website will enable universities and schools to access and utilise it.

The exhibition begins in the rotunda of the CSMVS building with a model of the Dholavira (3000 to 1500 BCE) site. It flourished as an important trading centre and was distinguished by its urban planning, architecture and sustainable water management systems.

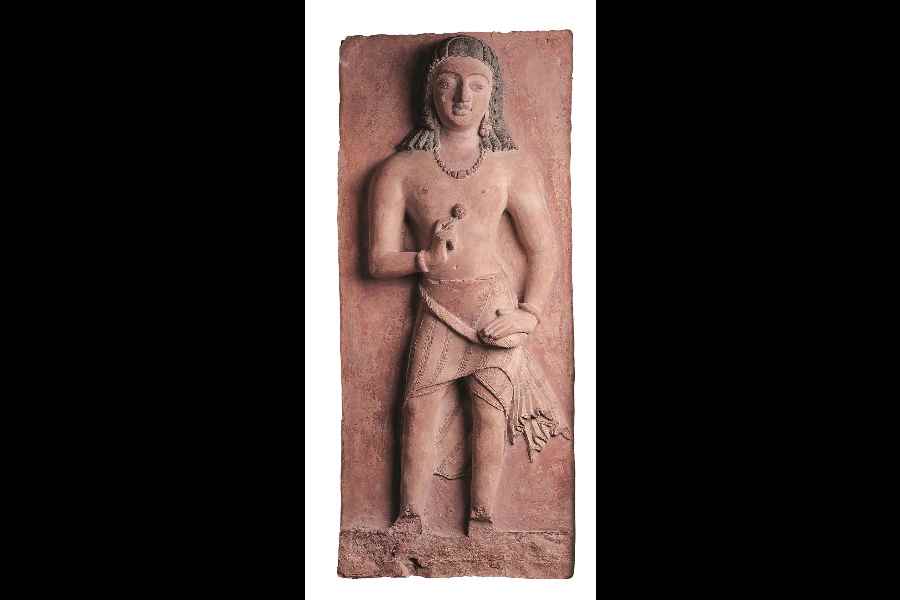

A wall and the floor of the rotunda recreate Dholavira in its heyday. The model is surrounded by mostly original objects from the four river cultures of Harappa (fired clay animals, miniature pots, a fired clay mask and jewellery from Mohenjo-daro) as well as Egypt (quartzite statue of scribe Pessupher), Mesopotamia (gypsum Praying Man) and China (a painted earthenware official for the afterlife).

Trade and culture connected them. Symbiosis instead of a clash of cultures. Beadmakers from Gujarat demonstrate how hollow carnelian, lapis lazuli and agate beads similar to the ones found in Mohenjo-daro are still produced.

The Dholavira model leads into the new educational gallery dedicated to the ancient world. It took four years to set it up.

Marion Ackermann, director general of Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, admired the “human measure” of the gallery, that it is “not overwhelming”. Of the exhibits, she mentioned the terracotta votive womb, 4th to 2nd century BCE, Etruscan, Italy, a moving reminder of the high rate of maternal mortality then.

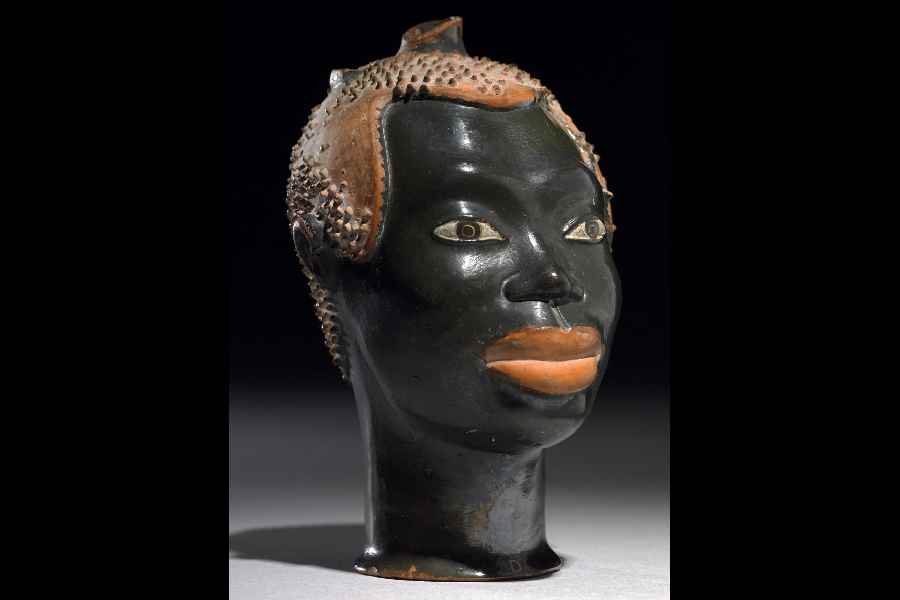

Perfume bottle in the form of a youth’s head glazed ceramic, Vulci, Italy; c. 510-500 BCE; From British Museum. Courtesy: Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), Mumbai

We are effortlessly transported to a different time and space. Imagine encountering a terracotta Harappan plough model (2600-1900 BCE), a wood Egyptian ploughman (1900 BCE) and his burly Roman counterpart in marble (2nd century CE), as you enter. A clay dog with brown glaze barking, a small tubular pig of nephrite in repose (both 25-220 CE) found in China. A terracotta ram found in Mohenjo-daro, Pakistan (2600-1900 BCE).

This is unprecedented. Asian and Mediterranean art are rarely seen together,” says Thorsten Opper, lead curator of this project, from the British Museum.

The showstopper is a painted mummified sacred cat from Roman-ruled Egypt (1st century CE) whose CT scan playing on an accompanying screen reveals its linen bandages and broken neck for dedication in a temple. Flashback via modern technology.

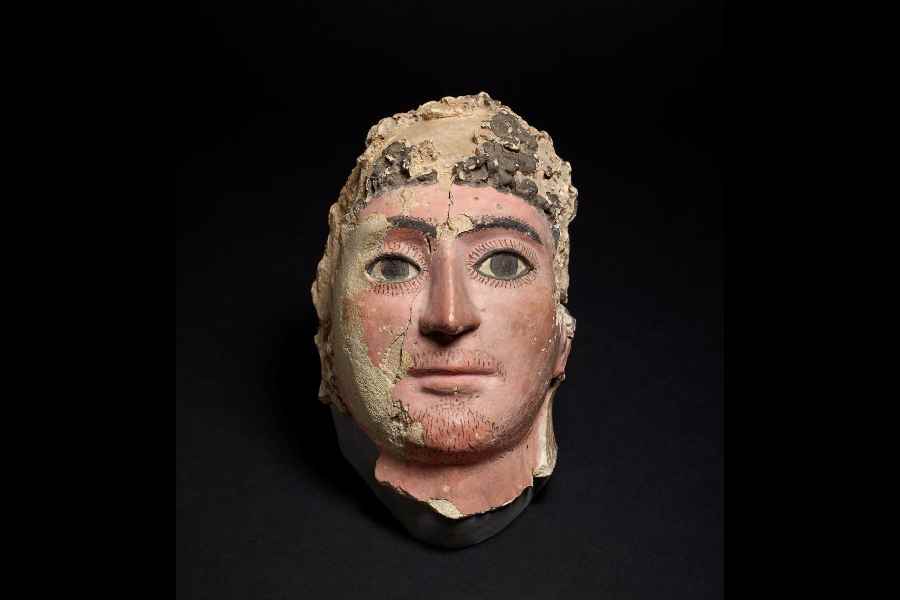

Mummy mask, Plaster, 2 cent. CE, Roman Egypt; From British Museum. Courtesy: Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), Mumbai

Commenting on the cross-cultural exchange, Salam Kakouji, chief curator and manager of the al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait, said: “We should do more of this. Western museums have come to us to show our gems.” The institution loaned 11 pieces, including the bronze figure of Anahita from Iran (300-500 CE).

It’s through a medley of carefully chosen objects such as these and by opting for a thematic as opposed to a chronological approach that this new gallery retells the story of the efflorescence of ancient civilisations beginning with the Harappan civilisation and terminating with the Gupta Empire in 6th century CE.

Concurrently, the gallery weaves the narrative of how agrarian societies learnt to write, one of mankind’s greatest inventions; how rulers held sway over their empires in far-flung regions; the precariousness of human lives in those days and how they dealt with life and death; the development of sea trade around 150 BCE in India and how business with the Roman empire and later China grew, while Mahayana Buddhism spread far and wide.

Clayware with brown glaze, China, Han Dynasty (25-220 CE); From Museum Rietberg. Courtesy: Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), Mumbai

The gallery ends with the two great centres of learning: Nalanda in Bihar and Alexandria in Egypt.

The juxtapositions reveal the commonalities and differences of disparate cultures. Each object has a riveting story to tell and a thousand research papers to launch. A female figurine of marble from the Cycladic Islands (2600-2500 BCE) that could have been an Amedeo Modigliani creation; a Romano-British stone mosaic (1st-2nd century) depicting Bacchus, the Roman god of wine and ecstasy, riding a leopard or panther. He had led a legendary expedition to India. The rondel was discovered in London.

Naman Ahuja, who teaches art and architecture at Jawaharlal Nehru University, feels the lack of competitiveness is the exhibition’s “greatest achievement”. Major cultures are brought together without any of them affecting a condescending attitude. The exhibition pleads for empathy with the other.