Two-time Oscar nominee Matthew Libatique is no stranger to the world of big, sweeping cinema. The celebrated Hollywood cinematographer has been a frequent collaborator with Darren Aronofsky, shooting the director’s best-known films like Pi, Requiem for a Dream, The Fountain, Black Swan, Noah and Mother! He was nominated for an Academy Award for Black Swan as well as for Bradley Cooper’s directorial debut A Star is Born.

Now, Libatique — the son of Filipino parents who migrated to the US — is receiving high praise for his work on Don’t Worry Darling, that releases in Indian theatres this Friday. Directed by actor Olivia Wilde, the psychological thriller focuses on a couple — played by Harry Styles and Florence Pugh — living in an experimental utopian community in 1950s California. The film aims to explore the tyranny of patriarchy, disguised as domestic bliss.

Don’t Worry Darling may have met with mixed reviews, but Libatique is receiving a lot of credit for creating a visually impressive landscape with sonic colours and frenetic scenes.

Over a long-distance Zoom call, The Telegraph chatted with Libatique on the vision and visuals of Don’t Worry Darling, his vast body of work and why cinematographers are in “danger”.

You have just shown Don’t Worry My Darling, as well as The Whale, at the Venice Film Festival. As an individual as well as a person of cinema, how significant is it to get back to physically showcasing films at festivals?

I feel very fortunate. Coming off the lockdown, the first film that I shot was Don’t Worry Darling. I took off from the last day of Don’t Worry Darling and directly went into The Whale. Back to back, I felt lucky to be able to shoot these two wonderful films, where I got to work with Olivia (Wilde) and Darren (Aronofsky) respectively. And for both these films to be shown at the Venice Film Festival is extremely mind-blowing. I am proud of both films for different reasons.

It was wonderful to be at Venice in person. At first, it didn’t dawn on me. But then I was sitting at the centre and I saw the press on the right hand side of the Excelsior, and I was like, ‘Wow! We are here... we are back again!’ I saw people enjoying themselves. My favourite thing at a film festival is seeing people walking in and out of a theatre... the excitement of that. When we were all inside the same room for the press day of The Whale it started dawning on that this is very special... the pandemic hadn’t allowed us to do something like this for two years. It was a case of normal becoming special! (Laughs)

Olivia Wilde has said that you were an integral and indelible collaborator in creating the world of Don’t Worry Darling. What was that experience like for you?

It came with its challenges. Primarily, it was shooting the house set... Jack (played by Harry Styles) and Alice’s (played by Florence Pugh) house because the back of it was actually a photographic backing, and I had this anxiety of whether I would be able to make it look real, and how much could I get away with shooting into that backing and not rely on visual effects.

I am proud to say that I didn’t rely much on visual effects. The success of that house, beyond its beautiful design, is that it has a relationship with the outside. And that helped us merge the gap between our interiors shot on set and the exterior Palm Springs house.

Olivia has done an amazing job in motivating and creating and inspiring her collaborators to stay within the same visual world. Now when I look at the film, every discipline that has gone into it has followed her orchestration. From beginning to end, the film is visual music to me.

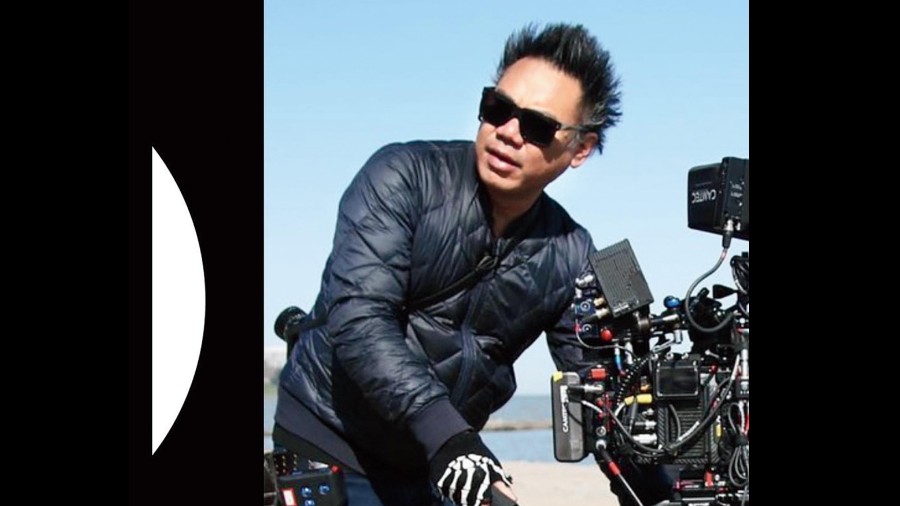

Matthew Libatique

I do think that we are in danger. People are only interested in what’s in front of the camera. And now everyone is in front of the camera because of TikTok, Instagram... everyone has become their own performer. And societal mentality is gradually shifting to believing that’s what is important

You just said how making this film made you anxious. Even after so many years in the business and with the kind of work that you have done, how do you explain this feeling of anxiety?

It’s always good to do things that you haven’t done before. Technically, my world is always changing. Lights have become lighter in weight, they have become electronic... the cameras are digital, they are more sensitive. So even though I may have done something similar before, perhaps the camera this time has to be more revealing. That’s always a challenge.

Each film is a first for me. I forget the things that I have done in the past. I do draw on my experiences but going in, I don’t assume anything.

That’s because every director is an individual. If you take my work with Darren for example, we don’t rely on what we have done in our previous movies together. We have a lot of shared experiences. If I am working with somebody for the first time — like with Olivia in Don’t Worry Darling, though I did do a short film with her earlier — things can change. What may be a close-up for one director may not be so for another. So I try not to assume anything because that creates expectations. It’s better to be open.

How much did working on this film push you as far as your craft is concerned?

Before this, I had never shot an entire action sequence for a film. On Venom, I had a wonderful second unit to rely on, and we had a litany of second-unit shots in Cowboys and Aliens. I did some of the work with the stunts, but when there was just a stunt rig with no actor involved, I didn’t shoot it. So doing the action sequence in Don’t Worry Darling was an interesting experience for me.

The Indian film industry makes a lot of films, but the people who work behind-the-scenes, including cinematographers, still don’t get the credit that’s due to them. More often than not, it’s the actors who emerge as the face of a film. I know things are better in Hollywood, but have you ever felt shortchanged?

That’s a good, good question. The Oscars award sound design, composers, editors, cinematographers, costume designers in the main award show, on the telecast. There has been some debate whether they should continue with that, but credit should be given to the Academy for actually doing it for as long as they have... even though they took away the editing segment this year and put it at the beginning of the telecast.

So because of the recognition that the Oscars give us — as well as the BAFTAs, which do a similar thing — we are in a relatively good space.

But I do think that we are in danger. People are only interested in what’s in front of the camera. And now everyone is in front of the camera because of TikTok, Instagram... everyone has become their own performer. And societal mentality is gradually shifting to believing that’s what is important. That’s what we need to keep an eye on. I am sorry that wasn’t a hopeful answer! (Laughs)

Is there a myth about cinematography that you would like to bust?

People shouldn’t assume that the cinematographer is just looking for a beautiful shot. A really good cinematographer always looks for the best shot. And that may not be where the perfect depth and light is... it may be just the opposite. If the director wants to put the camera in the right place as opposed to a beautiful place, then we as cinematographers need to figure out how to make that work.

Our top picks

Libatique (right) with frequent collaborator Darren Aronofsky

Requiem for a Dream

One of Matthew Libatique’s earliest works with Darren Aranofsky, this psychological drama focusing on drug addiction is considered a classic, all thanks to Aronosfky’s vision and Libatique’s creative cinematography that presented the film as a dark thriller-horror, painting a morbid picture of addiction in many forms.

Iron Man

Libatique showcased his prowess in the sweeping scale his cinematography brought to Iron Man and Iron Man 2, with reviews hailing how he “captures the soul inside the machines”.

Black Swan

This Aronofsky film earned Libatique his first Oscar nomination, with the latter coming in for praise for his supple hand-held cinematography that glided around its characters and was both horrifyingly visceral and visually beautiful.

A Star is Born

Notching his second Oscar nomination for Bradley Cooper’s directorial debut, Libatique shot the concert scenes in the film with both an epic and intimate quality, and the romantic scenes in an immersive manner.