Veteran actress-filmmaker Aparna Sen on Friday voiced concern over what she described as a steady erosion of serious, constructive film criticism in the age of instant reactions.

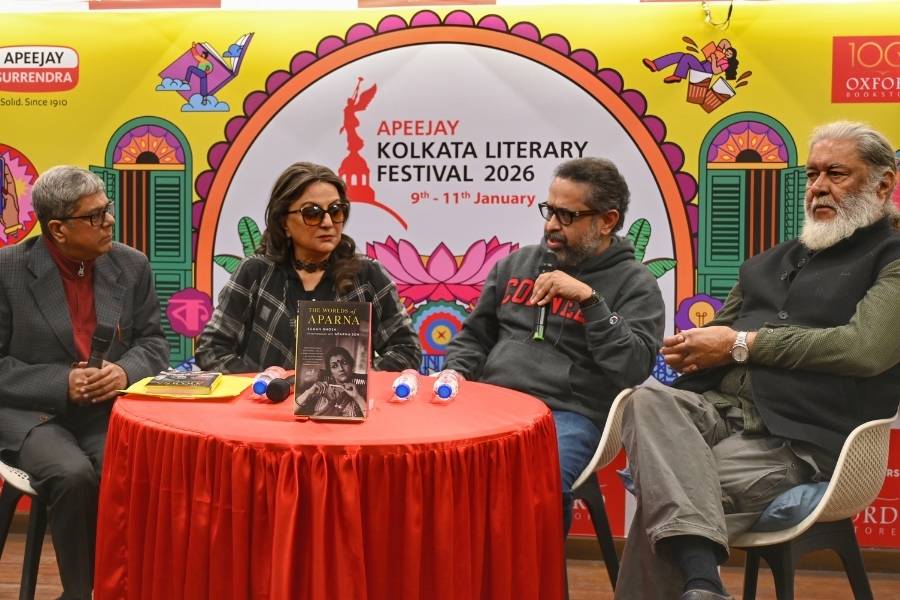

Speaking at a session titled ‘Aparna Sen Unplugged’ on the opening day of the Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival 2026 at Oxford Bookstore on Park Street, Sen was in conversation with filmmaker Suman Ghosh and academician Kalyan Ray, moderated by Raju Raman, programme consultant at Victoria Memorial Hall.

Sen was unsparing about what she sees as a culture of haste. She said she listens carefully to criticism that is “constructive”, but draws a distinction between good criticism and “instant coffee” reactions.

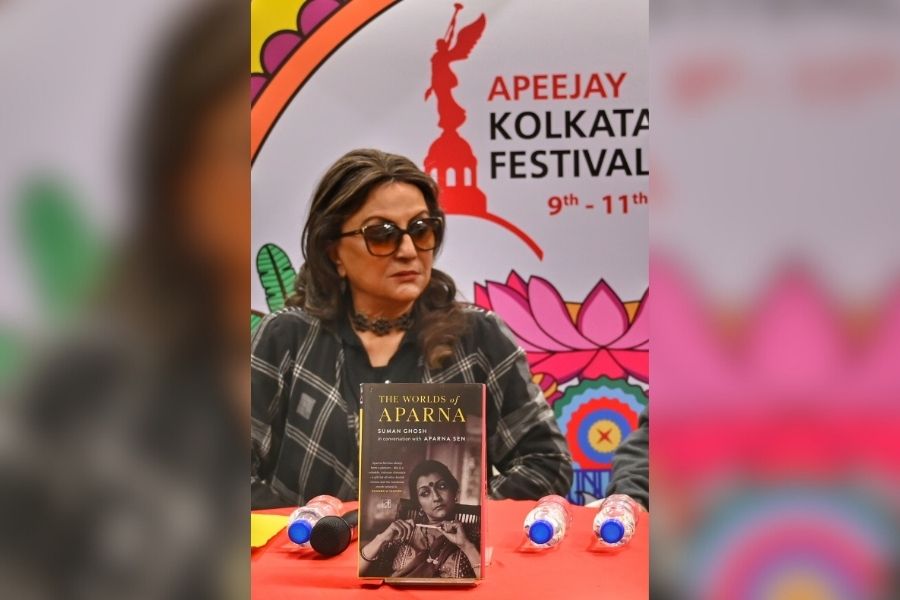

Sen said she draws a distinction between good criticism and 'instant coffee' reactions

“Today there is this instant coffee entertainment,” she said. “You just see a film or read a book and like it, don’t like it. Maybe you haven’t gone deep enough, but you form your judgement.”

Invoking her father, noted critic Chidananda Dasgupta, Sen said criticism, at its best, begins with an effort to understand the film, and sometimes requiring more than one viewing.

“There is nothing I can do to stop people forming judgements on a first viewing,” she said, “but when someone comes out of a film like Paromitar Ekdin with tears in their eyes and says, ‘We have children like this and nobody talks about them,’ then I know I have touched a chord”.

Ghosh echoed her concerns, arguing that “serious criticism” has become rare. While naming a handful of contemporary critics whose work he still values, he relies on a small, trusted circle for honest feedback.

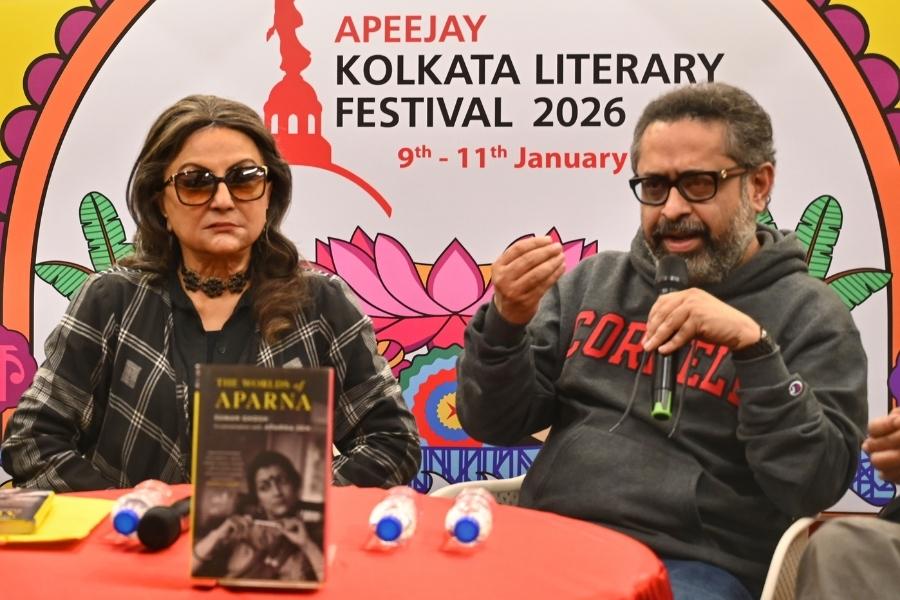

Suman Ghosh echoed Sen’s concerns, arguing that ‘serious criticism’ has become rare

The session also touched on how Sen evaluates her own films. The filmmaker, 80, said she judges them by whether they “hold together” and remain engaging over time. She cited 36 Chowringhee Lane and The Japanese Wife among the works that give her the greatest satisfaction, even as she admitted she continues to see flaws in her films.

Ghosh added that he views Sen within a ‘gharana’ of Bengali cinema rooted in humanism and lyricism, starting from Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen to Rituparno Ghosh.

The discussion repeatedly circled back to Sen’s sustained engagement with characters pushed to the edges of society, be it the mute widow in Sati, the special child in Paromitar Ekdin, or the mentally ill-woman wandering the streets in 15 Park Avenue.

(L-R) Raju Raman, Aparna Sen, Suman Ghosh and Kalyan Ray

Kalyan Ray linked this aspect of her work to the idea of the “subaltern”, noting that Sen’s films present marginal figures “not as tokens, but as real presences”.

Responding to the observation, Sen said she had never set out with a theoretical framework in mind. “I talk about things that I understand,” she said, adding that only in retrospect does she see how consistently her work has engaged with “marginal life”.

In 15 Park Avenue, she recalled, the film only came together for her when she imagined “a mad woman roaming around the streets”, a figure who, she felt, cut across class and social boundaries and mirrored the inner life of her protagonist, played by Konkona Sensharma.

“That was very important to me,” Sen said. “But oftentimes, this happens without me realising why I do it.”