Book: MISSING FROM THE HOUSE: MUSLIM WOMEN IN THE LOK SABHA

Authors: Rasheed Kidwai and Ambar Kumar Ghosh

Published by: Juggernaut

Price: Rs 599

Anyone interested in democracy and representation will find this book to be very important. It compellingly documents the yawning gap between the rhetoric of representation for women and the actuality of their absence, especially of Muslim women from the House. The referencing of the House is subtle and coded — not only do we find a shocking lack of Muslim women in the lower House of Parliament (Lok Sabha) but we also find references to the domestic situation of women and the relative lack of access to self-empowerment. In terms of methodology, it adopts a life-history approach as it tracks the lives and the labour of individual Muslim women who with help and despite hindrance made it to the House.

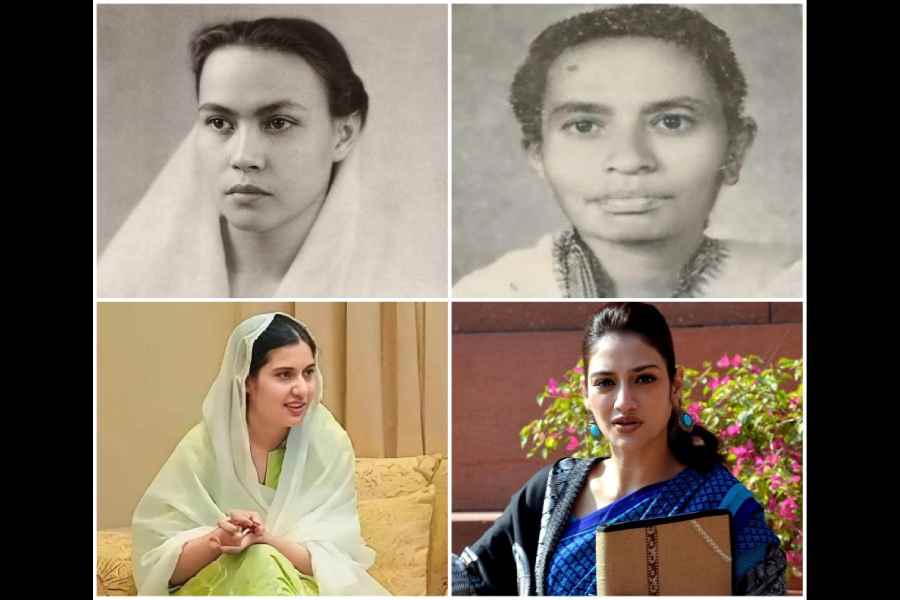

Some numbers first. Barely 18 representatives in the Lok Sabha are documented over the last seven decades and out of nearly 7,500 MPs since 1951, only 0.6% have been Muslim women. More stark is the fact that out of 18 Lok Sabhas constituted till June 2024, in 5 Lok Sabhas, there was not a single Muslim woman. What accounts for this marked absence? Is it an offshoot of deliberate discrimination against a minority community and of its women? Is it to do with the pressures that Muslim women face in a patriarchal home that makes agency of any kind a real challenge? Some of these questions form the staple of the book that sets the context and takes us through the life journeys of 18 women in a manner that the analysis becomes self-evident. There is the ‘dynastic’ factor, wherein women coming from established political backgrounds apparently enjoyed a head-start but this in no way was either the norm or the only story. Women were not simply proxy politicians for their husbands and fathers; on several occasions, they were able to carve out a very special place for themselves. The life story approach is inspiring as it unravels the stories of women who have been forgotten and whose lives hold out clues to the conundrum of low representation and to the unexpected elements that make up the complex idea of India, however threatened and interrogated.

The electoral success of Mofida Begam in Assam is a good starting point. A crusader for gender equality, her record in Parliament was impressive as she navigated a range of issues over which she demonstrated a good understanding. Her retreat from politics was sudden following the death of her husband and she in her later life gave up her estate to charity, the Assam Falah society. She is forgotten — hardly anyone knows of her struggles and, yet, hers is a life that is a microcosm of the lives of millions of Indian Muslim women. Her counterpart in Banaskantha in Gujarat is Zohraben Akbarbhai Chavda, who was a grassroots activist and a committed Congress Party worker. Her victory in 1962 in the Lok Sabha election was decisive and it gave her the opportunity to distinguish herself as a vocal parliamentarian. Especially impressive was her willingness and enthusiasm in taking up causes of agricultural reorganisation and farming practices, including that of the use of pesticides. This was not a case of an unthinking politician — someone who was incapable of responding to changing situations; she was an astute politician who worked towards a vision. The list of such women goes on and includes more recent entrants who cut their teeth

under very altered circumstances. Take the case of Iqra Hasan, the progressive face of politics in UP or that of Nusrat Jahan, whose entry into politics from stardom indexed a new social equation in Bengal politics under the banner of the All India Trinamool Congress.

The social anatomy of the politicians identified by the authors shows common features; most of them before the 1980s were part of an older history of agitation and Congress politics; many of them enjoyed the privileges of caste and education and fitted into roles that were part of a particular secular fashioning of politics. Later entrants like Nusrat Jahan came from backgrounds such as cinema and staked their claims to a new ecosystem of politics that is constituted by social media, the entertainment industry, and populist ideas of redistribution. The only limitation of the book is that it tells you what the status of Muslim women’s representation is but does not give you the why. The analysis is not as incisive as one would expect from the effort. As a first step in identifying the problem, it is an important effort, but as a diagnostic, it is only partial in its efficacy.