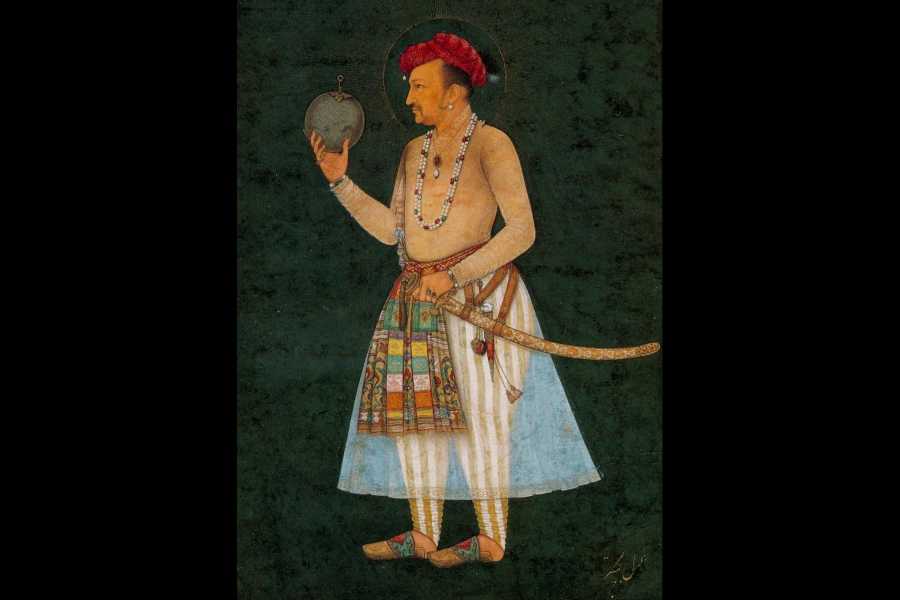

Book: AFTER ME, CHAOS: ASTROLOGY IN THE MUGHAL EMPIRE

Author: M.J. Akbar

Published by: Bloomsbury

Price: Rs 699

Remember 3 Idiots’ wildly popular message about the pitfalls of putting too much pressure on children by compartmentalising them into pre-decided boxes? Now, imagine you are anointed the saviour of the Mughal empire and the “Luckiest Star in the Firmament of Felicity…” even as you emerge from your mother’s womb. But, dear reader, you need not spare a thought for the poor baby; he is now known as one of the greatest kings India has ever had — Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar. News of Jalaluddin’s birth came as ‘auspicious’ news to the embattled Humayun. Fleeing as he was after the disastrous Battle of Kannauj, he still found time to sit down at the fort of Umarkot and pore over the horoscope drawn up for his son’s birth by Maulana Chand, and seeing that it promised “a resurrection of the empire”, went on with renewed optimism towards possible salvation in Lahore and beyond.

After Me, Chaos provides an insight into how stargazing “played a significant part in royal decisions…” The narrative is engaging enough. After all, why wouldn’t a common reader enjoy knowing exactly how much the stars influenced the decisions of kings? M.J. Akbar’s descriptions are almost cinematic, his imagery expansive, and his prose flows with confidence. But pick up this book only if you are aiming for a languid stroll through the minds of the major Mughal emperors, stopping at an anecdote here, reading about an eccentricity there. If you are looking for a well-organised, composed chronicle, which will give you a deeper understanding of the importance of astrology in

the Mughal empire, you

shall be sorely disappointed. More than half the account has little to no relation to

astrology. For instance, page after page discusses how some Mughal emperors were teetotallers, while others could not go a day without copious amounts of wine and opium. Akbar the author is quick to pay obeisance to Akbar the emperor for maintaining cordial relations

with the Rajput kings, while some sections seem to be

entirely hagiographic venerations of the rulers: Jahangir, for example, is praised for

refusing to entertain “sectarian quarrels” and for believing “in the universal peace promised by all religions”, while Aurangzeb is castigated for reinstating the jiziya, with no evidence presented whatsoever that the heavens might have directed these decisions.

The subdivision of chapters is even more confusing. One would think that a chapter devoted largely to Aurangzeb, the last major ruler in the Mughal dynasty, would bring the account to a close, especially given that the Alamgir had been told by a horoscope drawn up by Fazil Khan — the same horoscope which had predicted almost every event in his life with startling accuracy — that “[t]here would be chaos after he was gone.” But no. The book continues for another chapter, telling the readers about Babur, the progenitor of the dynasty! This haphazard arrangement often throws off the more absorbed reader. The fifth chapter begins with how Shahjahan believed he was the second lord in his dynasty, after the legendary Amir Taimur, to be born in the conjunction of Jupiter and Venus. However, in the same paragraph, the tale shifts to how Akbar had decided whether or not he would go to war against Kashmir based on portents and omens divined by his advisers.

I cannot foretell if readers will enjoy this book. Was Akbar’s wisdom, political acumen and religious egalitarianism brought about only by ‘good fortune’? Or is this blind superstition snipping through the pages of history?