When India and the European Union announced the trade deal on Tuesday, the elephant in the room was Donald Trump’s tariffs that have singed both sides.

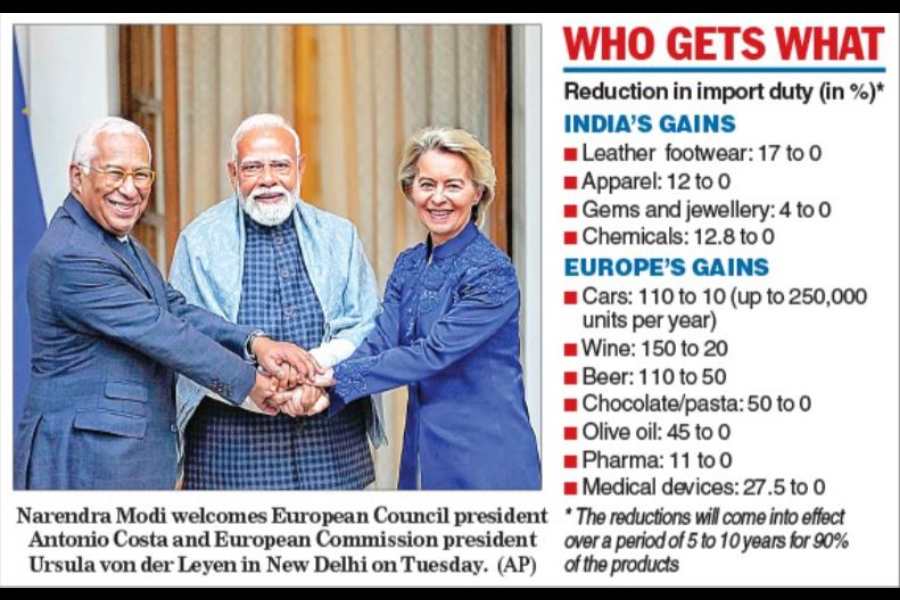

Neither side publicly mentioned the US but both Prime Minister Narendra Modi and European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen referred to the turbulence in the global polity.

“Today, the global order is undergoing profound turbulence. In this context, the partnership between India and the European Union will strengthen stability within the international system,” Modi said. Trump has imposed 50 per cent tariffs on Indian goods.

Von der Leyen said in her remarks to the media at Hyderabad House: “Two giants who choose partnership, in a true win-win fashion. A strong message that cooperation is the best answer to global challenges…. It brings together India’s skills, services and scale, with Europe’s technology, capital and innovation. It will create levels of growth that neither side can achieve alone. And by combining these strengths, we reduce strategic dependencies, at a time when trade is increasingly weaponised.”

Commerce minister Piyush Goyal sought to summarily dismiss a question on whether the Trump tariffs acted as a unifier in getting India and the EU to agree on the deal, saying: “I don’t think we even discussed this at any point of time.”

Tuesday’s agreement was widely followed internationally and most commenters saw the Trump hand add a sense of urgency to the decision-making in India and the EU to make concessions and get the deal done.

Constantino Xavier, a senior fellow at the Centre for Social & Economic Progress, said in a post on X: “India and the European Union have achieved what 1-2 years ago was thought impossible: meeting halfway, working beyond templates and domestic constraints, to strike an economic deal that was promised and negotiated for 25 years. This would not have happened without the massive geopolitical churn unleashed by the US, China, Russia — in a time of need, both sides have moved beyond mere commitments and have become friends in deed.”

Writing in the French newspaper Le Monde, political scientist Christophe Jaffrelot said: “For both the EU and India, these agreements serve a political purpose: a way to show the world there are alternatives to the United States, at a time when President Donald Trump is shifting the geopolitical landscape and imposing significant tariffs on countries that have long considered themselves US allies.”

Goyal dwelt on how the FTA had been in the works for 20 years with discussions beginning in 2006. “Sixteen rounds of negotiations were held. Sadly, in 2013, efforts were aborted and almost nobody ever imagined EU and India would be able to come up with such a robust partnership agreement as has been finalised.”

Negotiations were relaunched in mid-2022 but elections in India and the European Parliament in 2024 resulted in the “heavy-lifting” for the deal being done after the visit of the European trade commissioners to India in February 2025.

In his opening remarks, Goyal hinted at the sense of purpose with which both sides approached the negotiations: “Both sides agreeing to focus on what is good for both, leaving the sensitive issues aside and therefore coming up with a very balanced, equitable and fair, free trade agreement which is a win-win for all sections of industry both in India and the European Union.”

Both sides have divergent views on Russia and China. India’s relationship with Russia is a cause for concern for many European capitals. And, Europe has not taken the kind of confrontational position vis-à-vis China the way the US has on occasions.