|

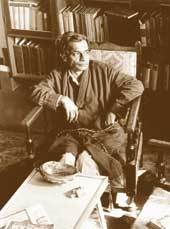

| Author Buddhadeva Bose. A Telegraph picture |

In his final days Buddhadeva Bose (1908-1974) had often repented that no one except close relatives and friends performed his plays (though Souvanik’s Patha Jhore Jai had a long run, Bose was not satisfied). But he had said that there would be a time when people whom he would never see or know would stage his plays. In his centenary year his words seem to be coming true.

One of the sessions at the recent three-day national seminar organised by Sahitya Akademi to mark Bose’s birth centenary on their Taratala premises was devoted to his plays. Dramatist Manoj Mitra chaired a discussion on November 26 with scholar Prabhatkumar Das, stage personality Sunil Das and Salil Bandyopadhyay, whose group Theatron was the first to produce Bose’s full-length play Tapsvi O Tarangini within months of Bose’s death and followed it with Pratham Partha, Sankranti and, more recently, Nepothey Natok.

Among newer plays in the city are theatre group Bohurupee’s Kalsandhya and Nattayan’s upcoming production of Bose’s Sankranti and Pata Jhorey Jai.

Bose is known primarily as a poet, short story writer, novelist, essayist and scholar. But he had been associated with the stage from the age of 12 or 13, when to overcome his habit of stammering, he turned to poetry and theatre. He formed a little troupe in his village in Noankhali performing Meghnadvadh Kavya and Nabin Sen’s Kurukshetra.

But why were so few of his plays produced during his lifetime? Was it because the theatre directors of his time were not ready to take on the challenges he had thrown from time to time in terms of theme, interpretation and form?

Kumar Roy of Bohurupee called Bose an exceptional dramatist, one who continued relentlessly to test his medium of expression and his imagined audience. At the seminar Prabhatkumar Das pointed out that in 1927, when Bose was studying English honours at Dhaka University, he had written and directed Ekti Meyer Jonye. The play was performed at the Jagannath Hall but minus an on-stage kissing scene. In 1933 his play Jedin Phutlo Kamal was the first play to have both male and female actors at Dhaka’s North Brooklyn Hall. Pratibha (Ranu) Shome, whom he later married, led the production.

But in Calcutta Natyaniketan aborted a production of Bose’s play Ravan because actress Nihar Bala found the characterisation of Sita objectionable, even amounting to “sin”.

Henceforth it was mostly Pratibha’s enthusiasm that saw the staging of his plays Anuradha in the courtyard of Jogesh Mitra’s house, featuring friends Premendra Mitra and Jyotirmoy Roy. Later Pratibha initiated the plays Rother Roshi and Maya Malancha (with sets by Jamini Roy).

After shifting to Kobita Bhavan (on Rashbehari Avenue), Bose attempted to establish the Little Theatre Group. “The attempt failed,” says Das, “but it was remarkable that he should have attempted to link the worlds of literature and theatre so long before the group theatre movement began.”

A gap in theatrical activity during his teaching assignments in the US was compensated by a spate between 1965 and 1974 during which he wrote Tapasvi O Tarangini (which won him the Sahitya Akademi Award), Kolkatar Electra, Satyasandho, Kalsandhya, Punormilan, Anami Angana, Pratham Partha, Sankranti, Prayashchitta followed. It’s said that Bose’s involvement with Jadavpur University’s comparative literature department and subsequent exposure to Western classics and mythology and his research for the book Mahabharater Katha had sparked off these plays.

Manoj Mitra said that Bose’s detailed stage directions “almost shot- by-shot like a film script” exhibit his keen understanding of the art of acting.

Kaushik Sen spoke of the challenge Bose throws to producers to interpret the long gaps in his plays with music, visuals or light, of the beautiful cadence of the lines and the way language and style changed according to situation. “When we did Pratham Partha, Bose’s works were being mostly read out with reverence at functions, as if no one dared to test it out on stage,” he laughed.