Around 1.15pm on Thursday, the office of a Trinamool Congress councillor in Behala had more than a dozen visitors.

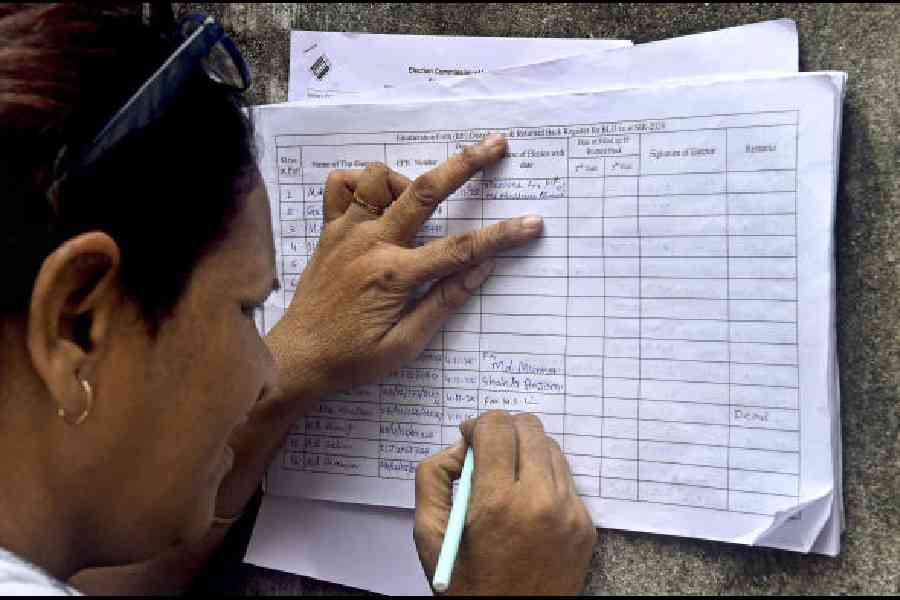

Most of them had queries related to the special intensive revision (SIR) of the electoral rolls. The office doubled as a camp to assist voters with the SIR.

“We have not had a five-minute break since morning. People are coming one after the other with questions,” said a volunteer.

In about an hour that Metro spent at the office, located at Behala West Assembly constituency, the volunteer addressed more than 15 people. There were two others like him, who remained equally busy.

The enumeration exercise was particularly concerning for the marginalised, suggested the conversations. While many of the visitors had valid papers, they were not well-versed in the process. The volunteers did their best to explain, but what emerged was an irrefutable spectre of anxiety that hovered over the masses, irrespective of their social standing.

A woman in her sixties, who works as a cook in the neighbourhood, was among the visitors.

She was unable to vote in the 2021 Assembly elections as she had moved to Pune for work. By the time the general election took place in 2024, she had come back home. However, she was turned away at the voting booth because her name was allegedly “not present on the voter list.”

“I thought it was a mistake and I would correct it later. But I never imagined something like this (SIR) coming. What happens if my name gets deleted from the list? Whenever I watch TV, news channels show that this SIR will lead to the exclusion of many voters. What if I am one of them? I have not been able to sleep in peace or eat properly for the past few days,” she told this newspaper.

To participate in the camp, she had forgone her duties at two residences. In a household that labours tirelessly to sustain the kitchen fire, this revealed much about the apprehension associated with the activity.

A volunteer at the office assured the woman he would find out if her name was on the current voter list and then match it with the 2002 list. The last such SIR in Bengal happened in 2002.

An Anglo-Indian couple had a flurry of questions for another volunteer. Neither of them features on the 2002 voter list.

The 49-year-old man was born in a railway hospital at Kharagpur, where his father, a railway employee, was posted.

He does not have a birth certificate. When he went to the hospital to get one, he was told to bring the discharge certificate after he was born. The discharge certificate could not be found.

The man has a baptism certificate issued by the church he is a member of.

His spouse possessed a birth certificate; however, her parents had relocated to Australia long ago. She holds a copy of her mother’s voter ID card, albeit one that contains a misspelling of her name.

“This whole exercise is so troubling. Suddenly, it feels like the burden of proof is on citizens. Who knew such a day was coming?” said the woman.

The volunteer advised the couple to keep all the papers in place and tell the booth-level officer (BLO) everything when she visits.

“People have a lot of questions that stem from the fear of being left out. We are doing our best to help them,” said Partha Sarkar, the councillor of Ward 128.