|

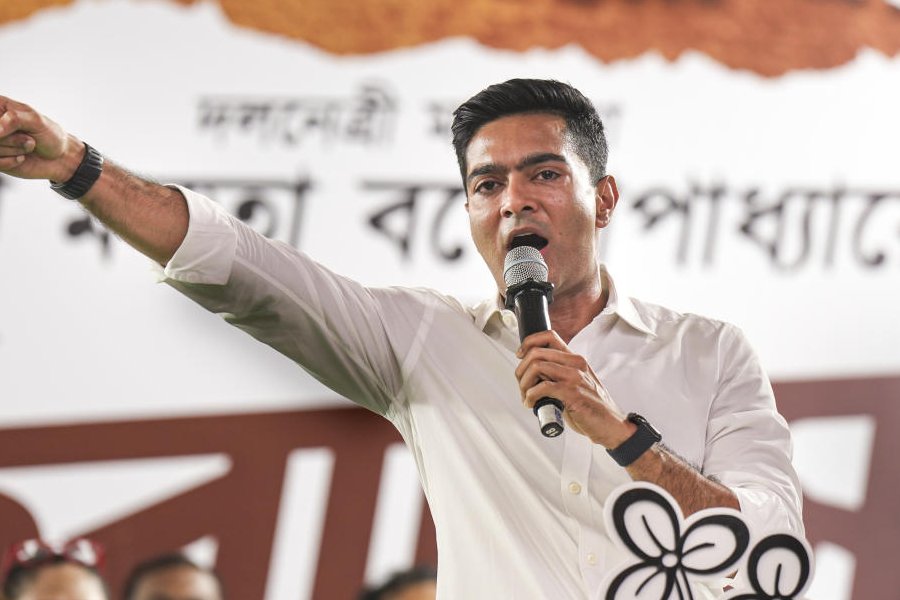

| Teko Modise during the South Africa-Mexico match |

Johannesburg: Among the many reasons for wishing for South African success in this World Cup, here is another: Teko Modise. Modise is the Bafana Bafana right winger, he has lost two uncles to AIDS-related illness and his mother is HIV-positive, too. This is a tragic storyline and yet one he shares with millions of his countrymen; the point here is that Modise is prepared to talk about it.

Indeed, in this hermetically sealed World Cup where media access to the players is so minutely controlled, he is prepared to break out of football mode. Some may describe the Wednesday against Uruguay as the biggest day of his life, but Modise has other priorities and is delighted to spend half an hour talking about them.

His life story is chilling. He is a Soweto street kid who, from the age of 8, never really had a home. He was abandoned by his father aged 7; his mother, Elisa, tried to give him parenting but failed.

For most of his childhood, he did not know where he was going to sleep each night, as he explains with the following unforgettable line: “The problem was when the sun set; where was I going to sleep, where would I eat? That was the problem every day. The worst part of my life was when the sun went down; I used to pray that night wouldn’t come.”

Until he was 6, he lived with his grandparents and his brother and sister. He was then taken in by his father for two years and thereafter he was a vagrant. He had about a year with his mother but the most consistency he got was when the coaches of the various football teams he played for gave him floor space on which to sleep.

“But I never knew if I would sleep where I slept the night before or would I get chased away? I don’t know what it feels like to grow up at home,” he says. “I also didn't have the opportunity to grow up with a mother. It got so bad that I didn’t care whether I lived or died.”

Modise’s way out was football. Aged 18, he was signed to a professional team in Polokwane, 200 miles north. It was there that he adopted the lifestyle that many in South Africa associate with professional footballers. As he says: “I used to enjoy what every young man does: partying, drinking, everything.”

But that changed in 2005 with a phone call from his mother. He had, by then, been working to close the distance between them. On the phone, his mother was straight up: she was HIV-positive. “The way she told me, she was not sympathetic, it was as if she had flu,” he says. “It was hard for me to understand. She had no emotions about it. I didn’t know how I was supposed to react.”

Modise reacted the way that much of South Africa has reacted, notably some of its leading politicians: he went into a state of denial. “I initially refused to accept it,” he says. “I didn’t want to speak about it because I couldn’t believe it.”

But it was the turning point of his life. Not immediately, but gradually he came to the decision that his lifestyle should change. Then, in consecutive years, 2008 and 2009, he lost two uncles to AIDS-related illnesses and he decided to go public. He cleared it with his mother and started talking about it, he became an ambassador for Brothers For Life, the awareness campaign, and, most significantly, he allowed himself to be publicly photographed being blood-tested for HIV/AIDS.

The reaction from his teammates has been fascinating. Only one of them has spoken a word to him about the campaign or his mother — that is Matthew Booth, who is also a Brother For Life. “Matthew is a born leader,” he says. “The others haven’t asked. But most South Africans don’t want to talk, we know that it’s there, we know what we’re supposed to do, but we won’t talk. That’s how bad it is.”

What is curious about his team is that Modise insists that, troubled though his upbringing was, almost all of them can relate to it, most of them were brought up in single-parent or divorced families. And he “knows that some others have lost relatives” to HIV/AIDS.

“But I am going to be patient,” he says. “It took me a while to get my confidence to talk about it. They may be the same.”

At the end of 30 minutes talking, Modise returns to his football world. And he does one final thing that makes him unusual for a footballer; he says: “Thank you. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to tell my story.”