Oh, boy! Even immortals turn senior citizens. No, wait a minute. That might be logically unsound.

Let’s put it this way. Age accompanies even those who have given us glimpses of what immortality means. That 25-year-old, for instance; in that summer of 1986.

How time flies. As if the years have wings; invisible, deceptive wings that make you seem the master of your destiny when all the while it is just your memory getting longer. But sometimes, what memory!

Think of that afternoon in Mexico City. World Cup quarter final, June 22. The young man gets the ball in his own half. He turns a circle, as perfect a circle as possible on a football field, then takes off on a weaving, mesmerising run through the England defence. Right. Left. Right. Right. Left. Beardsley, Reid, Butcher, Fenwick, Butcher again. All shaken off. Goalkeeper Shilton on the ground; then an explosion of delirium.

“Whenever I watch it again I can hardly believe I pulled it off...,” Diego Maradona would later say of his 11-second ballet of immaculate rhythm. Only a handful of times in the game’s history has the prologue been as captivating as the epilogue, if not more.

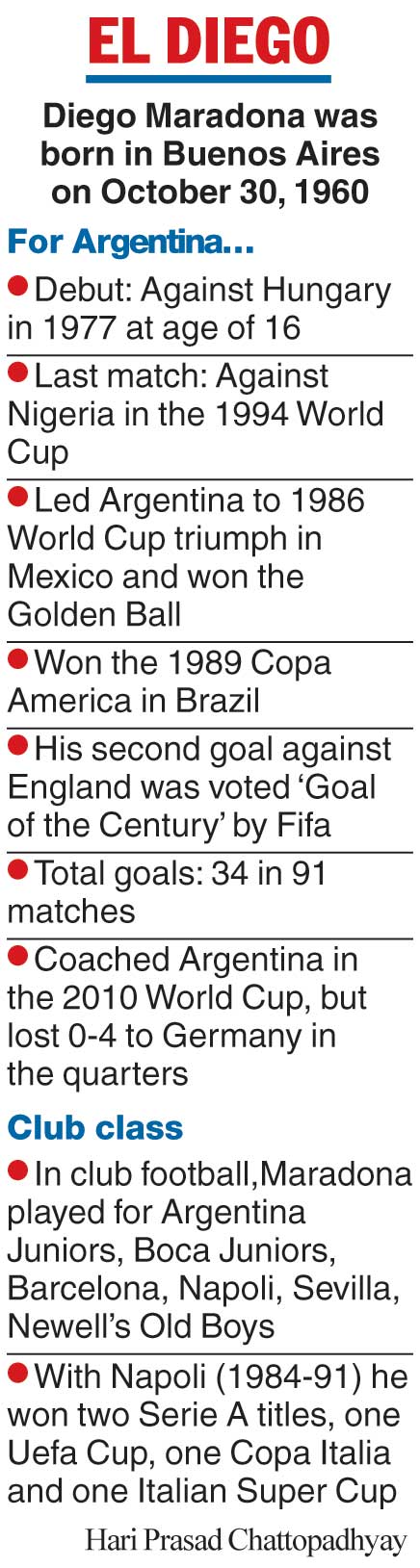

Thirty-four years on, come October 30, that cocky little sorcerer who had bequeathed to football its epiphanic moment of a century would turn 60 — the widely recognised cut-off age to become a senior citizen.

The arena has always been for the young; even those supremely gifted have to move on, not only in deference to time but also to the continual erosion of memory. What never erodes — unlike memory — is reminiscence, that ability to call to mind anything, anywhere.

For football lovers, Maradona’s run that day was one such moment, when time moved from the “mausoleum of all hope and desire” and beyond, in William Faulkner’s words, the illusion of victory or defeat.

Yet never had such a goal been so necessary for redemption. The 55th-minute goal had come barely four minutes after another, that too from Maradona. But that first goal didn’t come from the magic of Maradona’s feet; it would come through what the man himself would cheekily call the “Hand of God”.

This is what happened. The ball had looped down near the penalty spot. As goalkeeper Shilton, 6’1”, lunged forward, Maradona, barely 5’5”, flicked the ball into the net with his fist.

He then sprinted towards the corner flag, pausing a fraction of a second to look at the referee, before celebrating in full. Seldom had such illicit sleight of hand been legitimised by a refereeing blunder.

This 51st-minute goal, too, has burnt itself into memory — as a counterpoint to genius; a reminder that those blessed with immortal feet can also have hands of clay.

Maradona wasn’t done yet. A few days later — in the semi-final against Belgium — would come another moment of sorcery, this time legitimate. Pursued by defenders and cramped for space, his body seemingly out of balance, Maradona would place the ball past the goalkeeper, before sprinting away into a stumbling, celebratory run, as if time itself had stumbled and picked itself up in the same riveting momentum. Argentina — 2-0 up — were through to the final, and eventual glory.

In a way the goals sum up Maradona the man, a contradictory figure who would hit rock bottom eight years later when a failed drug test would send him home from the 1994 World Cup in the US. Not to forget his earlier years at Napoli, his deification in Naples, the Italian city that embraced him as a god but would also leave upon him the taint of cocaine and alleged links with the Camorra, a mafia-type secret society.

There would be moments of petulance, too, when Maradona opened fire with an air rifle at journalists a few months before the US World Cup.

Yet, it is between these extremes — the spectacular and the stained — that the story of Maradona unfolds: a flawed genius whose appeal endures still. That’s the paradox of fandom: while nobility demands reverence, it’s easier to identify with human failings. The reason heroes of great tragedy never suffer the bane of indifference.

Politics — the shared history of imperial exploitation — is another likely reason. He was, after all, the David who single-handedly surmounted the privileged Goliaths.

His early-life poverty, a childhood spent in a shantytown, may have played a part too — as a vicarious salvation, especially for those born to unprivileged homes. A kind of confirmation, however delusional, that fantasies might not be limited to fairy tales.

More likely, it’s a combination of all these factors — sealed emphatically by his bewitching wizardry. Memory cannot reject what the mind remembers.

Time has aged most of Maradona’s fans but the dazzle of his feet still plays out at sudden moments of reminiscence. As lucid as when a 25-year-old had glided past a thicket of English legs.

Oh, boy! Even immortals turn senior citizens.