THE KILLING OF OSAMA BIN LADEN By Seymour M. Hersh, Verso, £12.99

According to The Killing of Osama Bin Laden, a new book by Seymour M. Hersh, Barack Obama's White House fabricated much of the story of Osama bin Laden's death; lied about its decision not to attack the Syrian army; wilfully ignored intelligence regarding Syria's civil war; and was undermined by the joint chiefs of staff, the military officials meant to advise the civilian leadership, who instead conspired to offer secret aid to the Syrian ruler Bashar al-Assad.

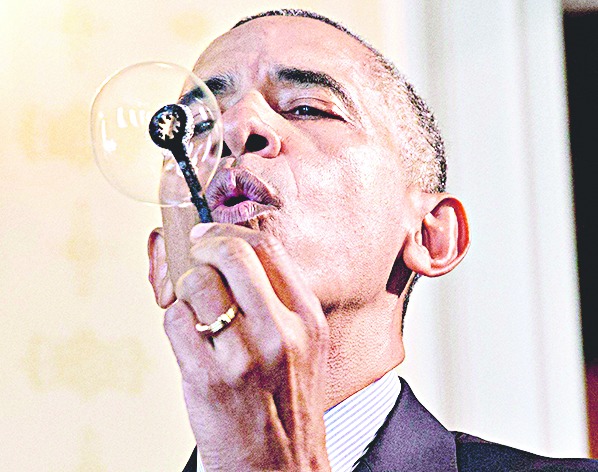

If all this is true, the current administration of the United States of America is frighteningly deceitful and inept. Even worse, Hersh might say, is how Obama's transgressions have gone blithely unquestioned by almost the entirety of the media, as well as by most of Congress. In his view, the result is a thick haze of conspiracy and acquiescence that is clouding the public's judgment of a widely beloved leader. Hersh seeks to dispel such illusions. Needless to say, his reporting has been scorned by the US government; but it has also been completely rejected by many of his fellow journalists. The Guardian and the website Vox are just two of the many outlets that have characterized Hersh as a "conspiracy theorist". Either Hersh has produced some of the most revelatory political journalism in recent times, or he has gone unhinged.

Hersh's previous investigative work is legendary. As a young reporter, he single-handedly exposed the government cover-up of a massacre of Vietnamese civilians by American troops in a village known as My Lai. It was a discovery that had a profound effect on domestic opinion of the Vietnam war, and a scoop that would define Hersh's career. Over the coming decades, he continued to write about misguided US covert operations, most notably Secretary of State Henry Kissinger's part in the US bombing of Cambodia and, later, the Bush administration's responsibility for prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib. Hersh's search for the hidden truth of My Lai has continued, in different forms, to the present day.

The Killing of Osama Bin Laden is a collection of four articles published in The London Review of Books over the last few years. Each one seeks to unveil morally dubious and strategically unwise secret elements of Obama's fight against terrorism. Each also relies on an unnamed "retired senior intelligence official" or a "former senior adviser" as its central source of evidence. Conspiratorial though they seem to some, these essays do not posit official corruption or hidden ideology: they are simply a chronicle of "lapses in judgment and integrity" that Hersh himself calls "confounding".

Some of the central claims of his book are persuasive. The official government story of the killing of bin Laden starts with "years of careful and highly advanced intelligence work," including waterboarding and other forms of torture, which led to the identification of a courier who could be traced to bin Laden's top-secret hideout in Abbottabad, Pakistan. Hersh's story, conversely, begins with a rogue Pakistani intelligence officer, who walked into the US Embassy and offered to divulge bin Laden's whereabouts - betraying a Pakistani effort to keep him as a highly valuable prisoner - in exchange for the $25 million reward advertised by the US.

Since his article was first published, Hersh's report of a "walk-in" has been corroborated by Steve Coll and Carlotta Gall, two respected journalists with their own sources, as well as by NBC News and Agence France-Presse. In addition, reports from Abbottabad itself suggest that Pakistani officials facilitated the American strike. All this casts doubt on the official narrative and lends credibility to Hersh's version of events, which also seem to clear up numerous improbabilities in Obama's account. To believe the US government, you have to believe, among other things, that bin Laden chose to hide less than a mile from the Pakistan Military Academy, in a resort town about forty miles from Islamabad, and succeeded in doing so without Inter-Services Intelligence ever noticing.

Hersh's prose is a relentless torrent of mutually supportive assertions. His tone is that of someone who seeks to show that only his interpretation of events is legitimate. In Hersh's writing on Syria, both a series of exposés and a strategic analysis of the civil war, this single-mindedness leads to omission and overstatement. Hersh argues that the August 21, 2013 chemical weapons attack in Syria was launched not by Assad - as Obama would have it - but rather by jihadist rebels in concert with Turkish intelligence officers, who failed in their attempt to provoke the US into a retaliatory strike after the West covertly uncovered their plot. Though Hersh does marshal much support for this seemingly elaborate theory, he does not disprove evidence compiled by various neutral groups, including the United Nations, that indicate the rockets used for the attack were fired from areas controlled by Assad into rebel territory, and that traces of sarin found at the site of the attack specifically match unique chemical elements of the government's stockpile. In general, Hersh's allegations of official duplicity in Syria rely too exclusively on a single anonymous source.

His criticism of the US strategy in the Syrian civil war is similarly blinkered. Hersh ridicules the insistence of the US that "Assad must go", arguing that only cooperation with Assad and Vladimir Putin will put an end to chaos in Syria. According to Hersh, the so-called "moderate opposition" has been defeated, and the only remaining alternative to Assad is violent extremism, namely in the form of the Islamic State and Jabhat al-Nusra.

This simple dichotomy between the overwhelmed "moderates" and the formidable jihadists leaves out many of the groups currently in control of Syrian territory, foremost among them the Kurdish fighters in the north. Many other rebel groups are currently being represented in peace talks by the Western-backed High Negotiations Committee, which includes Islamist fighters such as Jaysh al-Islam. Should these factions be considered no different from IS? What of the opposition forces still in control of much of Aleppo and currently engaged in new offensives in Latakia and Hama? Too much of Syria opposes Assad in too many different ways for the entire opposition to be conflated with its worst elements. To put into effect Hersh's suggestion of an alliance with the rebels' hated battlefield enemies, Assad and Putin, would require unthinkable repression.

In the least convincing parts of The Killing of Osama Bin Laden, Hersh seems to be thinking backward from conclusions he has already reached, ignoring contradictory information that lies outside his storyline. The best parts of his book, on the other hand, have far too much explanatory power to be dismissed lightly. If Hersh's most recent work is far from definitive, it is nonetheless a forceful incitement to greater reportorial scrutiny of America's ongoing fight against terrorism. "Our job is not just to say, 'here's a debate,'" Hersh has said of journalists. "Our job is to go beyond the debate and find out who's right and who's wrong."