|

|

| Summary trial |

A stray writing on the wall in the outskirts of the Chhatra district headquarters in Jharkhand catches the eye. “Maut ka badla maut, fansi ka badla, fansi. Dekho haal Suresh, Hiraman aur Hani ka, kar denge behaal, saaza dene walon ka (Death should be avenged by death. Look at the plight of Suresh, Hiraman and Hani, we will punish those who have punished them)” — read the ominous note, crudely etched in red.

This open challenge of the Maoist Communist Centre is for Hazaribagh’s additional district and sessions judge, Ashok Chand, who sentenced three Maoist guerrillas to death last month for a massacre in Beltu a couple of years ago in which 15 “class enemies and police informers” were butchered. Chand, who passed the landmark verdict, reportedly abstained from court for a few days until his personal security was tightened.

A string of death warrants passed against MCC and People’s War guerrillas last month has put the extremist groups on the offensive and triggered panic among the legal fraternity. Three judges in Jharkhand sought security cover after the rebels launched a poster campaign against them following their sentencing of members of the outfit to death in three massacre trials. The posters proclaimed “death for death”.

Of the three judges — the Gaya district and sessions judge Jawahar Chowdhury, the Hazaribagh additional district and sessions judge Ashok Chand and the Garhwa additional district and sessions judge Deepak Nath Tiwari — two have been assigned security. Security provisions to Chowdhury was pending as he was supposed to shift to Bokaro after retiring from the Gaya court on June 30. He had written to the home secretary and Bokaro superintendent of police, requesting personal bodyguards.

On June 8, Chowdhury had sentenced four MCC activists to death in the Barra massacre, in which 35 people were killed. Chand awarded death to three militants for the Beltu carnage on June 17. On June 26, Tiwari decreed capital punishment for four People’s War extremists for the Meral strike in which 16 villagers had been killed.

The judicial machinery is working overtime to rein in the extremists in the manner it knows best — by expediting trials and advocating the harshest of punitive action — death. But the extremists have turned the conventional legal wisdom to their advantage by taking the campaign against the legal system to the grassroots level and projecting the judiciary as anti-people.

The People’s War had called a Garhwa bandh on July 10 in protest against Chowdhury’s verdict, which was described as a blow to the process of “empowerment of the marginal groups and the fight against the reactionary feudal forces.” In a release, the Jharkhand-Chhattisgarh joint committee of the outfit said the “sentence...reflected the feudal mindset of the judges.” It went on to allege that the four youths sentenced, belonged to the backward Mahato caste and were innocent villagers who had picked up arms against the oppression of the landlords and “caste enemies.”

The argument seems to have found many takers at the grassroots level, sharply polarized along caste lines. The judges — a majority of them upper caste or hailing from the economically-affluent middle classes — are being portrayed as villains. The rebels are playing the traditional class conflict card to the hilt. According to sources, in every village-level meeting of the People’s War and MCC in Hazaribagh, Chhatra, Garhwa, Palamau, Latehar and Gaya districts, the class character of the judiciary is being discussed in the light of the death sentences to further alienate the Dalits, scheduled castes and other marginal caste groups from the judiciary.

The class and economic background of the death row convicts is lending credence to the ultra-left propaganda war. Most of the activists sentenced to death are from the deprived social groups and are hailed as heroes for fighting to solve some genuine problems. “It is wrong. They are poor villagers like any of us, but they have the courage the fight,” says a 60-year-old village mukhiya on the Chhatra-Gaya border, where the MCC has blasted a rock face to build a mammoth dam for irrigation.

In Hazaribagh, the extremists have been able to whip up a groundswell of mass resentment against all “upper caste babus”. Reports cite that the MCC has chalked out a strategy to target all police and VIP vehicles plying on the Ranchi-Patna highway, which pass through Hazaribagh town. The MCC has apparently decided to give a fitting replyto the government for the Beltu judgment. A soft stand of the villagers has helped. They are willing accomplices in the war against the system. The rebel strategy has also caught the police on the wrong foot, which had earlier expected the villagers to face the brunt.

The MCC seems to have scored two hits with its campaign against the judiciary. First, it has able to label the system feudal and turn the spotlight on the caste schism. Second, and perhaps the most significant, it has been able to uphold the superiority of its own parallel system of justice in its kangaroo courts.

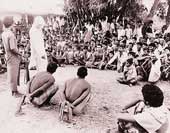

The courts, known as jan adalats and held at frequent intervals in remote villages inside the forests, dispense quick justice without the bother of protracted trials, complicated legal procedures and the accompanying costs. The system, touts a MCC sympathizer, is crude but simple for the illiterate and impoverished villagers who comprise the bulk of the MCC and the Peole’s War’s support base. The cases pertain to land disputes, betrayal, thefts, fraud, abuse and even marital discord. The harsh punishment, mostly death, instills fear among the villagers. “The jan adalat is above caste, creed and religion. It is pro-people. It caters to the needs of the grassroots, where injustice is rampant,” says a former activist-turned-social worker based in Hazaribagh.

The MCC is believed to have changed strategy in its battle against the judiciary. “Target the records, so that the cases cannot go to court,” is the new MCC refrain. The recent attack on the Paraiya police outpost, 65 kilometres from Gaya is a pointer to the changed tacks. The outfit torched the record room of the police station and killed three jawans, one of whom one was burnt alive. Justifying the offensive, a handout issued later proclaimed that, “The documents destroyed were instruments of oppression.”

The incident might have taken place in Bihar, but Jharkhand cannot escape the terror, for it is the epicentre of the churning. Over the past five years, the Jharkhand government has been fighting a losing battle against extremism.

According to a home ministry report circulated by L.K. Advani at a conclave of chief ministers from the trouble-torn states, Naxals in Jharkhand were responsible for 1,276 incidents of violence and 176 deaths in 1997, 185 incidents and 90 deaths in 1998, 318 attacks and 193 deaths in 2000, 355 acts of violence and 200 deaths and in 2001, 349 incidents and 157 deaths in 2002. The report cited that nearly 88 per cent of the violence in Jharkhand and Bihar was orchestrated by the ultra-left radical groups.

If this statistics is not a grim reminder of the scenario, then probably the state government will need another millennium to pull its act together.