I recently came across a book with the intriguing title, Lenin and Gandhi. Its author was the Austrian writer, René Fülöp-Miller. The book was published originally in French; what I read was the English translation, published in 1927.

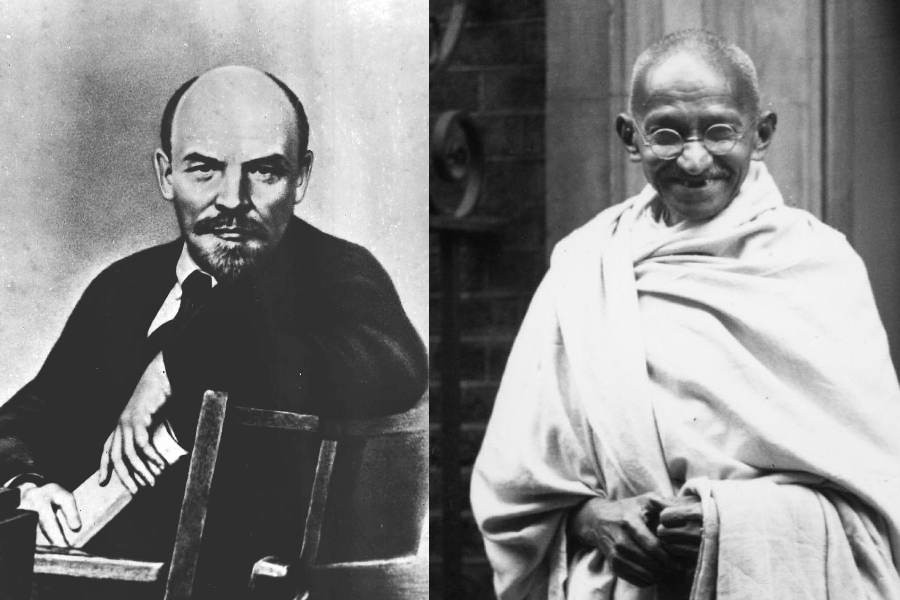

Back in the 1920s, a book-length comparison between Gandhi and Lenin made eminent sense. The two men were near contemporaries, who entered this world within six months of one another. Both were born middle-class, both driven by a passionate desire to emancipate the poor and end injustice. However, there were also key differences. Lenin was savagely polemical in his writings, whereas Gandhi exuded civility in public and in private. A related, yet much more important, distinction was that one worshipped at the altar of violence, whereas the other was devoted to the practice of non-violence.

So far as I know, the first writer to compare Gandhi and Lenin in print was the Bombay radical, Shripad Amrit Dange. In April 1921, Dange published a tract, sixty pages long, carrying the straightforward title, Gandhi vs Lenin. As a communist himself, Dange preferred Leninism to Gandhism but —perhaps because he had observed Gandhi in the flesh — retained a residual sympathy for his compatriot. He thus observed that ”the complete realization of the theories of both the systems in practical life is an impossibility. Gandhism suffers from too much an unwarranted faith in the natural goodness of human nature, while Bolshevism suffers from too much neglect of human interests and sentiments.”

Four years after Dange, an American Methodist minister named Harry Ward published an article called “Lenin and Gandhi” in the April 1925 issue of a journal named The World Tomorrow. Ward also noted that Lenin and Gandhi transcended their middle-class backgrounds and identified themselves with the masses through the ”bare simplicity of their lives”. He then turned to the contrasts. As Ward put it, “Lenin’s philosophy is a philosophy of power, his program a program of force. Gandhi’s philosophy is a philosophy of love, his program a program of non-violence… Lenin says we will overcome the force of the oppressor through more force of the same kind. Gandhi says we will overcome it by a different kind of force.”

Harry Ward saw Lenin and Gandhi as “the two most influential men of the period.” As he wrote: “On the conflict of ideas and ideals embodied by Lenin and Gandhi turns the future of mankind. The people at the bottom must come up into a larger life. Are they to get it by gradual accumulation and sharing on the part of those who now have more privileges and opportunities, or will they be forced into a struggle of power which will destroy the very elements of civilization?”

It appears that, in publishing his book on Gandhi and Lenin in 1927, René Fülöp-Miller did not know that Dange and Ward had trodden the same path before him. Like them, he suggested that both Gandhi and Lenin transformed their countries and the course of history through the compelling force of their personality. Each was carried along by the courage of his convictions, willing to struggle alone even when erstwhile colleagues deserted him. Each worked tirelessly to bring about constructive unions between different sections of society, between peasants and workers in the case of Lenin’s Russia and between Hindus and Muslims in the case of Gandhi’s India.

In some ways, Fülöp-Miller’s analysis ran along the same lines as his precursors. However, he was less ambivalent about the moral distance between Lenin’s political practice and that of Gandhi. He thus wrote that “hate was Lenin’s element”; he “knew no other means of dealing with political opponents but écraser, ‘crush them’”. That Lenin, who desired a class-less world without oppression, “could see no other way of attaining his end but naked brute force, is the most profoundly tragic thing in his peculiar destiny”.

On the other hand, wrote Fülöp-Miller, Gandhi’s “profound conviction of the universal truth of the Ahimsa idea made [him] decide to carry on the fight against personal and political enemies in all circumstances by means of love alone”. And further, that “Gandhi’s revolution is unique in history as a revolution of goodness and non-violence, under the leadership of a man who preaches understanding and whose motto is ‘Love your enemies’.”

In 1926 — a year after Harry Ward’s article was published, but a year before René Fülöp-Miller’s book appeared — a young British communist named Philip Spratt came to India to foment revolution. Unlike the Austrian or the American, he was not a writer but an activist and had no time to be even-handed or equivocal. He had chosen the path of Lenin. For a couple of years, Spratt roamed around the subcontinent, making contacts with Indian revolutionaries and assessing the prospects for revolution. Then, in May 1929, he was arrested and sent with his Indian comrades to face trial in the Meerut Conspiracy Case.

Spratt was in jail for almost a decade. While in confinement, he came to read a great deal about Indian history and philosophy, subjects he had previously little knowledge about. His readings made him look at Gandhi more sympathetically than his Leninist convictions had once allowed. On his release, he went to Sevagram to meet Gandhi. Drawing on their conversations, but to a far greater extent on Gandhi’s own writings, he published a book-length assessment of the pre-eminent Indian of the day. Here, Spratt sought to heroically reconcile the Lenin he had been taught to revere with the Gandhi he had now come to have a greater appreciation of. In his book, titled Gandhism: An Analysis, Spratt wrote: ”To leave crores of people in the present conditions of the Indian villages for a day longer than is necessary is a crime. The Russians have had to hurry excessively, to undergo much privation, and to resort to drastic coercive measures, mainly because of the danger of foreign invasion. Orthodox socialism, if it could afford to refrain from such abnormal steps,… could probably render India a habitable country, with a people reasonably educated, happy and prosperous, in half a century. Mr. Gandhi’s method would presumably take far longer. But its results might be of such value, and it is of such interest as an experiment in non-violence, the abolition of hatred from human affairs, and the observance of truth, that one could almost prefer it.”

We find here unconscious echoes of Harry Ward, with Spratt suggesting that while Lenin’s methods may possibly be more efficacious, Gandhi’s were certainly more humane.

Spratt had entered prison a convinced Marxist; he left it a confused one. Searching for a halfway house between Leninism and Gandhism, he joined the circle around M.N. Roy. In the late 1930s, this former associate of Lenin and long-time critic of Gandhi had started a new Radical Democratic Party, which ran a newspaper called Independent India, whose contents Roy himself kept close watch over.

In December 1941, Spratt, now married to an Indian woman and living in Bangalore, sent M.N. Roy an article for publication in his newspaper. Roy rejected the article as being excessively sympathetic to Gandhi. The manuscript of the article is unfortunately no longer available, but the nature of its contents is revealed in a letter that Spratt wrote to Roy. Here Spratt argued that Gandhism cultivated “self reliance, honesty, interest in public affairs, capacity to cooperate, [and] freedom from communalism”. He thus believed it could be a major force for “making the country fit for freedom (I did not say fit for socialism)”. Spratt had also, in passing, pointed out an “error” of Lenin’s — “that he thought bourgeois democracy a total fraud, worth making use of for revolutionary purposes, but of no value in itself. Actually, it is a most valuable achievement, and unless its chief features are preserved, i. e. political democracy, civil liberties, freedom of thought, etc etc, socialism will be no gain at all”.

Eighty years after Philip Spratt offered his two cheers for democracy, democratic regimes across the world are under siege. In Trump’s America, Orban’s Hungary, Netanyahu’s Israel, Erdogan’s Turkey, (and not least) Modi’s India, right-wing authoritarians are working strenuously to rob public institutions of their autonomy and stack the odds in favour of the party currently in power. The answer to such democratic backsliding, however, is not a bloody, Leninist-style revolution that results in an authoritarian, one-party State. Rather, one must seek to renew the vitality and promise of genuinely fair elections, a free press, an independent judiciary, an independent civil service, and other such institutions that have helped make ‘bourgeois democracy’ that ‘most valuable achievement’ of humankind.

ramachandraguha@yahoo.in