With an intention to improve the UGC Regulations 2012, framed 11 years before by the UPA II government, the University Grants Commission brought an improved vision, the Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions Regulations, in 2026. However, immediately, a section of general students expressed opposition to some provisions of the new stipulations. Responding favourably to the opponents’ arguments, the Supreme Court has now kept the 2016 Regulation in abeyance and ordered its review, for it believes that the provisions are vague and are capable of being misused.

The petitioners mainly expressed opposition to the separate mention of “discrimination only on the basis of caste or tribe against the members of the scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, and other backward classes”. The petitioners argued that there was no need to mention caste discrimination as it would be covered under the general definition of ‘Discrimination’, “which includes all forms of discriminatory treatment, including caste”. They also argued that a separate mention of caste may result in dividing society, adding that ragging should have been made part of the Regulations. The judges agreed with these points and supported the review by a committee of eminent people.

After careful consideration, it appears that the opposition to the separate recognition of caste discrimination faced by SC/ST/OBC students is not guided by a proper understanding of the theoretical considerations underlying the concept of discrimination related to social identities like caste, ethnicity, race, colour and religion. A separate mention of caste discrimination is necessary in addition to its inclusion in the general definition of discrimination.

A discussion on the concept of discrimination will bring clarity to the issue. In theories, the term, discrimination, pertains to a social group as a whole based on an ascribed identity. Discrimination thus relates to social groups such as caste, tribe, race, colour or gender and not to an individual. It refers to group norms that define the behaviour of one group towards others that are discriminatory in nature. This is a common feature, which applies to all social categories. At the same time, discrimination may differ among social groups with respect to the source and the nature of discrimination. If there is variation in the treatment of untouchables, Adivasis, women, religious, racial or colour groups, they will have to be treated differently. It will be a gross mistake not to recognise the differences in the nature of discrimination embedded in them.

What is the nature of caste discrimination faced by Shudras and untouchables? Nobody brings as much clarity on this as does B.R. Ambedkar in the books, Who were the Shudras? and The Untouchables: Who Were They and Why They Became Untouchables. The caste system is a social organisation of Hindus whose governing principle is inequality. But it is not governed by a common notion of bipolar inequality as between low and high caste, male and female, or Black and White. Instead, it is governed by the principle of graded inequality. Everybody suffers from caste discrimination but some castes suffer more than others. In this structure of graded inequality, the discrimination among castes increases in terms of denial of social, economic and religious rights as we climb down the caste pyramid. The untouchables, located at the bottom of the caste hierarchy, suffer the most. But unlike other castes, they suffer the additional stigma of impurity and pollution. Their touch, approach, and sight cause pollution to the castes above them. They are thus subjected to physical and social isolation, antagonism, contempt, and hatred, which deny them personhood and dignity. The Supreme Court treated the crime against them as unique.

There is thus a degree of difference in the discrimination faced by a Shudra and an untouchable. The Shudra (OBC) suffers from denial of social, religious and economic rights. But the untouchable suffers doubly, from the denial of equal rights as well as the stigma of impurity. There are similar differences among other social categories as well. For instance, Adivasis and Dalits were put in the same category in the Protection of Civil rights Act 1955 and the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, but the sources and the nature of their discriminations differ. The Adivasi does not suffer from untouchability; his/her discrimination is associated with ethnicity, which leads to physical and social isolation. Unlike the untouchable, the Adivasi’s social and physical isolation and residential segregation are not related to Hindu religion but to custom and tradition. Similarly, the discrimination associated with race and colour in India is not based on religion; its origin lies in ideology on account of which some races and people of colour are treated as inferior. The discrimination of women and Shudra/untouchables has common roots in Brahmanical religion insofar as both suffer from denial of rights to property, education and social status. But unlike untouchables, women do not face untouchability. Similarly, the discrimination faced by religious minorities such as Muslims, Christians, Buddhists or Sikhs is not the same as that of caste and untouchability.

These insights gleaned from theories and empirical studies imply two things. Dalits, Shudras, Adivasis, women as well as some racial, ethnic and religious groups face discrimination and should be a part of the general definition of discrimination. But, at the same time, the sources and the nature of their discriminations vary across groups. These need to be listed separately. This will help address group-specific discriminations such as the caste-based discrimination of the Shudra, the social and physical discrimination against the untouchable, the diverse isolations of the Adivasi, the racial discrimination of students from the Northeast and so on. This implies that the argument by the petitioner that caste discrimination of SC/ST/OBC should not be mentioned separately is not sustainable.

The differential treatment of low-income and junior students cannot be confused with the group-based discrimination of SCs/STs/OBCs/women/religious minorities. Therefore, the suggestion that students facing ragging or the differential treatment meted out to low-income groups should be included under the category of group-based discrimination is untenable. These are instances of individual-based differentiation that can be treated under the general grievances mechanism. The grievances of high-caste individuals can be treated under normal grievance redressal mechanisms as well.

Earmarking jobs for economically weaker sections is necessary but considering these under reservation based on group identity by the Supreme Court was not justifiable. The new suggestion to include the harassment of economically poor Dalits by their better-off counterparts is also an idea without merit.

The Supreme Court has decided to set up a committee of eminent people to look into the matter. It would be wise to include some academicians in that body to understand the issue of discrimination from an academic angle to institute legal safeguards.

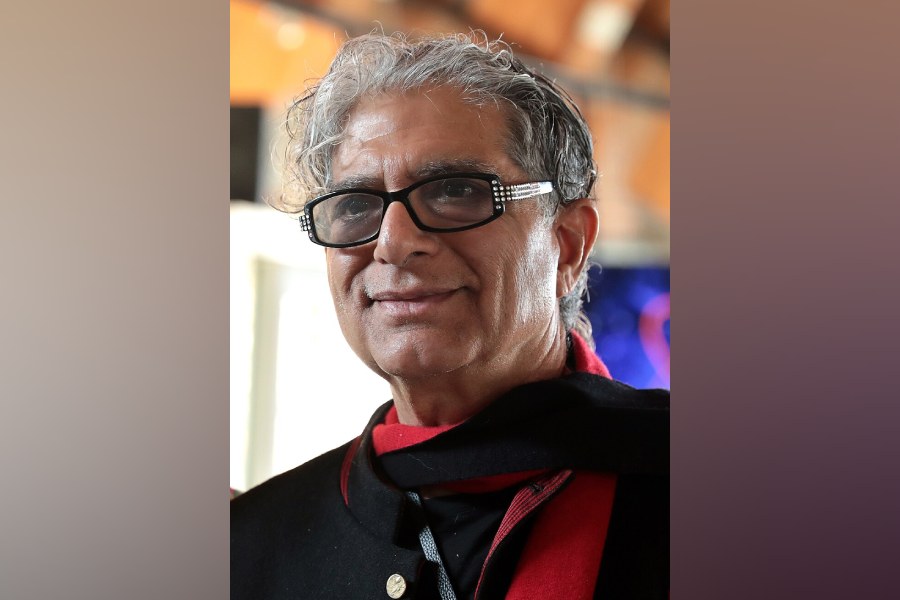

Sukhadeo Thorat is former chairman, University Grants Commission