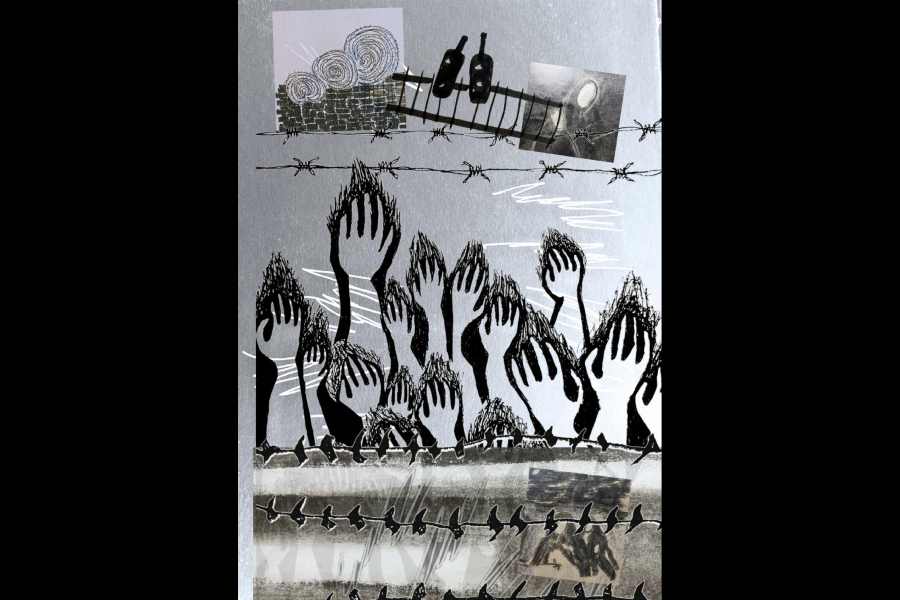

The demarcation between India and Bangladesh, formerly East Pakistan, was actually drawn 77 years ago by British lawyer Sir Cyril Radcliffe. He had been commissioned to do so in just five weeks based on the religious demography of the region. No matter that he had never visited India.

The Radcliffe Line, drawn on paper, was officially announced on August 17, 1947. The line cut through much more than physical land. It cut through human lives, alienating farmlands from homesteads and markets from produce.

For years, the border remained porous, with people crossing the line to go to weekly markets, visit relatives, arrange marriages and attend village fairs. Then, things started to change after the India-Pakistan war of 1965 and again in 1971 when Bangladesh was born. Barbed fences were installed in most places, strict patrolling enforced to prevent illegal entries and check trans-border crimes. Never mind that the strict vigil disrupted the fundamentals of an agrarian community, criminalised the most customary of transactions and turned “smuggling” across the border into a viable business.

Manjira Saha, a schoolteacher and independent researcher, has been study-

ing life in the borderlands for nearly a decade, from 2009 to 2018. She has written a series of books and monographs, including the recently released Border e Sonsar or Border and Family Life. It is she who took me on a guided tour of the Indo-Bangladesh border more than once; it is with her help that these snapshots have been gleaned. But before you get to them, here is the technicalese to help you understand the very uncommon predicament of their protagonists. “Zero line” is the actual boundary bet-

ween two countries sharing a border. And “no man’s land” is the name for the buffer zone extending 150 metres on either side of the “zero line”.

SNAPSHOT 1

Gate open. Gate close Picture this. The border. Ananta Sardar is waiting on the no man’s land or buffer zone on the Indian side. Behind him is the Changrakhali border post in Bangladesh’s Chuadanga district. Stretching in front of him is the barbed wire fencing and beyond it, there is a black gate, and beyond the gate lies Nadia’s Tungi border post.

Ananta is not alone. Milling around the gate are about two dozen men, women and children. With spades and sickles, water bottles and tiffin carriers, sacks, bales of jute... All of them are waiting.

The gate will open at noon. The moment it does, the crowd will deposit photo IDs with BSF jawans who will check each person thoroughly before letting them proceed.

Ananta is a farmer. He lives in Dharampur village close to Tungi, but the patch of land he owns falls in the buffer zone. Every day there are three timeslots when the gate opens, which means Ananta has three chances to access his land and get back home. That day he was not feeling well. I overheard him telling another farmhand, “If I

get stuck I won’t be able to get home before dusk.”

He tells me, “Otherwise, I am lucky that only my farm is here. Many villages are in the buffer zone, many people live here. Imagine how they have to negotiate between home and homeland.”

One such village is Kulopara. The villagers have to bring out their ID proofs every time they have to enter their own country. There are 339 such villages, across six districts of West Bengal, where the barbed fence came up following an international border agreement — the joint India-Bangladesh guidelines of 1975. More barbed fences have come up in the last three decades.

SNAPSHOT 2

The Backbenchers Agents have an uncanny knack of sniffing them out. Smugglers’ agents. During the journey to and from school, they spot those students. Most of them belong to poor landless families living in border districts. The modus operandi is simple. Agents pull them aside casually with a seemingly innocuous errand or two — will you pass this packet to my friend or throw this thing over the fencing for that chap beneath that tree. The reward is attractive, a princely sum of ₹ 100 for every successful delivery. Little does the student know that the packet contains narcotics or gold or a bundle of currency notes.

He — most often a boy — is more focussed on his reward; treats himself and his friends to a pack of cigarettes or a bottle of cheap liquor with the money. When Saha introduces me to a group of such boys they tell me with glee, “Sir, it’s like a game of cricket. You throw a packet from the treetop to the other side of the fence and you get big money.”

They also swim across waterholes or rivers with the smuggled goods. The lure of easy money encourages them to first bunk classes and then drop out of school. They are gradually groomed for tougher assignments — smuggling cattle, then weapons, even explosives and finally women.

Then some day, these seasoned smugglers are shot by the patrolling security forces. Sometimes they die, oftentimes they are thrown into prison and many times they are maimed for life.

SNAPSHOT 3

The lovestruck cattle smuggler When Saira Khatun, a student of Class 11, started having seizures, her mother took her to the other side of the fencing for treatment. They travelled via a zone in Kulopara, where there are no barbed fences, only pillars. On the way, they met a young man called Nasir who fell in love with Saira.

Nasir took mother and daughter to a qualified doctor in Kushtia, a small town in Bangladesh. The doctor prescribed expensive medicines which the family couldn’t afford.

But then Nasir bought the medicines and soon he started visiting the family if only to see Saira. He gifted the mother and daughter saris, cosmetics and costume jewellery. And all was well till the day Saira’s father, Mansur, learnt that Nasir was a cattle smuggler.

Mansur banned Nasir from entering their homestead. But Saira continued to meet Nasir secretly after school. A year later, they decided to elope and settle down on the other side.

One winter morning, Saira escaped home to meet Nasir at the mango orchard near the border. But when she reached the spot she didn’t find Nasir. Within minutes there was some commotion, followed by gunshots. The moment she understood there was a BSF raid, Saira ran home.

Later that day, she heard that a smuggler had been shot dead by the guards. His name was Nasir Sheikh.

SNAPSHOT 4

Gede Sundari That is the name for the early morning local train from Sealdah to Gede, a border checkpoint on the Indian side. Should you ever find yourself in the ladies’ compartment, you might come away thinking you are hallucinating — for every other woman in the compartment appears to be pregnant.

It is indeed a Kahani moment except that the baby bump is not some prosthetic but contraband items being smuggled across the border.

Once the train crosses Taraknagar station on the Indian side, the women rush into corner seats, loosen their saris or salwars and don specially designed jackets of plastic stuffed with bottles of Phensedyl syrup and other narcotics.

These jackets are lined with strips. Each strip is fitted with 12 bottles. A woman of strong build can carry as many as five strips — three on the torso and one strapped to each thigh. They can walk, run and even jump with such contraptions on their body.

These women jump out of the train before it rolls into Banpur station and disappear into the bushes close to the border. Agents of smuggling rackets, known as “linemen” pay them for their labour. One such woman at Taraknagar station told me, “The money is good. It pays for my childrens’ tuitions.”

SNAPSHOT 5

Has anyone seen Asmatara? The teacher called out from a paper — “Asmatara Khatun; age, 16; guardian’s name, Hamida Banu; residence: Linepara…”

A tall dark teenager with curly hair appeared at the registration desk.

The teacher asked, “What happened to your guardian? What is your father’s name?”

The girl replied, nonplussed, “My father left us. He’s gone to the other side and got married to a younger woman. My mother works as a domestic help, on this side.”

The teacher was hauling her up for bunking class and not appearing in the half-yearly exam.

Turned out, Asmatara’s mother had eloped with a “lineman” and settled down on the other side.

The girl too lived there with her new family, a big family of 12 members.

In her new life, Asmatara woke up at the crack of dawn, finished her domestic chores, then crossed the fence with a bundle of clothes and switched from hijab to school dress.

The teacher told me and Saha that she most likely attended school for the free mid-day meal. After she returned home in the evening, she had to go to a madrasa to learn Arabic and basic etiquette. “Rules are very strict there. We are not allowed to watch TV or chat with boys,” Asmatara told us.

When I asked her if she was a citizen of India or Bangladesh, she replied, “Beyond the barbed wire, there are pillars with numbers inscribed on them. Those with English (Roman) numbers indicate India, Bengali numbers are in Bangladesh. Our village has both types of pillars, it’s confusing.”

When I visited the area next, Asmatara was gone. Her classmates couldn’t tell for sure what happened to her. Some of them said she got married and settled down on the other side, others said her mother sent her somewhere far away through an agent.