A new medical review suggests that interrupting long periods of sitting with simple foot-and-calf exercises may help lower post-meal blood sugar and improve circulation, offering a potentially easy way to prevent and manage diabetes.

The review by four Indian doctors has found that just three minutes of simple resistance exercises — such as seated soleus push-ups — every 30 minutes during prolonged sitting can reduce post-meal glucose levels by 39 to 52 per cent.

The researchers cautioned, however, that most available studies were short-term, and that the long-term benefits and the best way to do these exercises — how often and how intensely — remain unclear.

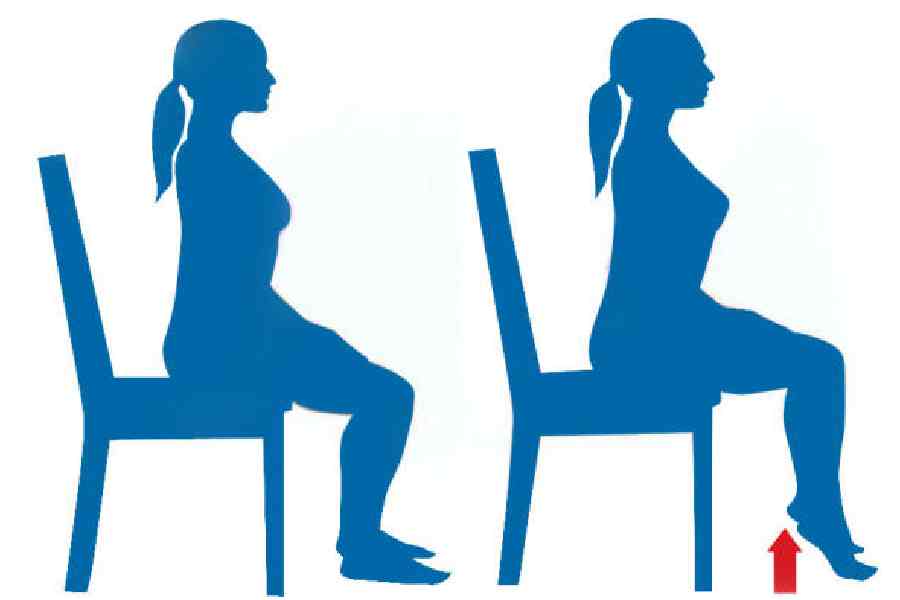

Soleus push-ups involve sitting with the knees bent, keeping the toes on the floor, and repeatedly lifting and lowering the heels to activate the calf muscles.

“Exercises like the soleus push-ups do not involve walking, jogging, or weight-bearing activities,” said Anoop Misra, director of the Fortis Centre for Cholesterol Obesity and Diabetes in New Delhi, who led the review of multiple earlier studies evaluating non-weight-bearing lower-limb exercises.

“Soleus push-ups done while seated make them particularly suitable for people engaged in prolonged sedentary work or those unable to do conventional exercises due to cardiovascular or musculoskeletal disorders or advanced age,” Misra told The Telegraph.

The research review was published in the journal Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews.

Amid growing international evidence over the past 15 years that muscle stretching aids glucose control — and rising social media promotion of the practice — Misra and colleagues pooled clinical studies from 2011 to 2025 to evaluate its role in diabetes management.

Muscle physiologist Marc Hamilton and his colleagues at the University of Houston in the US were among the first, through a 2022 medical research paper, to flag soleus push-ups as a way to boost the muscle’s ability to burn energy for hours without fatigue.

Other simple resistance activities the new review evaluated include (1) squats to activate the quadriceps, hamstrings and gluteal muscles, (2) alternate knee lifts toward the chest with deliberate contraction of gluteal muscles to increase hip and thigh blood flow, and (3) heel lifts while standing to stimulate the calf muscles and improve blood flow.

“The stretching and contraction of the muscles turns them into a sink for blood sugar — we call them a metabolic sink,” said Raju Vaishya, an orthopaedic surgeon at the Apollo Indraprastha Hospital in New Delhi and member of the review team. “This helps lower blood sugar.”

The review described the resistance and stretching exercises as low-cost, easy-to-adopt ways to help prevent or manage diabetes, particularly because some of them can be done while sitting.

But the researchers cautioned that important questions remain. Most studies have involved small groups of patients tracked for short periods, so it is not yet clear how long the benefits last or how often and how hard the exercises should be done.

They also said that for people who are able to do regular aerobic activities such as walking or jogging, these movements should add to — and not replace — those forms of exercise. “Larger and longer studies are needed to confirm long-term gains on diabetes and how they translate into benefits for heart health,” Misra said.