Salil Chowdhury would have turned 100 this November. The composer, lyricist, writer and political thinker, born on 19 November 1925, shaped modern Indian music with ideas far ahead of his time. On his birth centenary, we revisit the legacy of an artist who blended folk sound with Western orchestra while adding a touch of social consciousness to his music.

Chowdhury’s early days as a musician

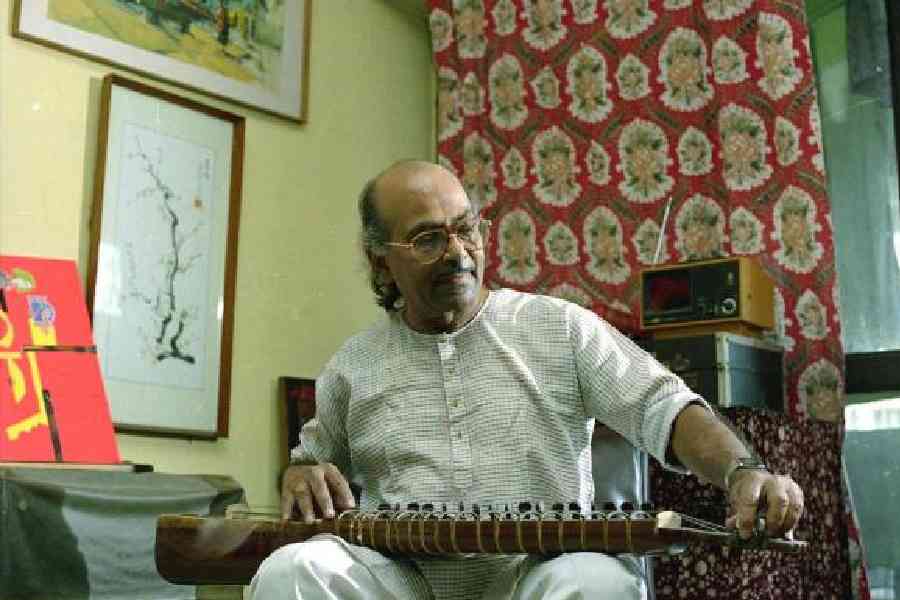

Chowdhury grew up in Assam’s tea gardens and rural West Bengal, where he picked up the folk traditions. He started playing instruments like flute, harmonium and esraj early on in life. He would also listen to Western symphonies floated from an Irish doctor’s gramophone in the tea estate where he lived. His elder brother’s orchestra allowed him to experiment, listen and understand how arrangements work in real time. This influence is evident in his compositions like Itna Na Mujhse Tu Pyaar Badha (Chhaya, 1961).

A political awakening

The 1940s changed him. The famine, the peasant uprisings, and the harsh realities of Bengal’s rural belt drew him towards the Communist movement. At IPTA gatherings, his protest songs gained traction. Bicharpati tomar bichar korbe jara stood out as a powerful anthem of the time. These years sharpened his worldview and shaped his artistic direction. For Chowdhury, music and politics were never separate domains.

The rise of a distinct soundscape

Chowdhury brought a new dimension to Indian film music. He wove folk and classical melodies with Western-style voicing, counterpoints and harmonies. He shifted the rhythm section away from predictable patterns, using the piano and other percussive tones to give his songs a cleaner edge.

His song arrangements also had a touch of freshness. The flute, ukulele, strings and brass gained prominence, creating a refreshing mix unfamiliar to Indian audiences in the 1950s.

The birth of choir movement

Chowdhury believed in the power of collective voices. The Bombay Youth Choir, founded in 1958, became India’s first secular choir. Soon after came the Calcutta Youth Choir, which worked closely with IPTA.

His Bombay days

Bimal Roy introduced Salil Chowdhury to Hindi cinema with the landmark 1953 film Do Bigha Zamin. Chowdhury wrote both the story and the music. The film’s international success helped establish him as a composer with an unusual blend of empathy and craft.

Then came Madhumati (1958), a watershed moment in his career. The soundtrack — featuring songs like Aaja Re Pardesi, Dil Tadap Tadap Ke, and Suhana Safar — showcased his range.

The Malayalam stint

The 1960s took Chowdhury to the Malayalam film industry. The songs of Chemmeen became instant classics. His work with lyricists Vayalar and ONV Kurup shaped an entire era of Malayalam music.

The Hindi-Bengali switch

Salil Chowdhury often carried his melodies across languages. Many of his Bengali songs found new lives in Hindi, but he never treated these versions as direct copies. He adapted each tune with fresh arrangements, new rhythmic choices and a sharp understanding of the film’s mood.