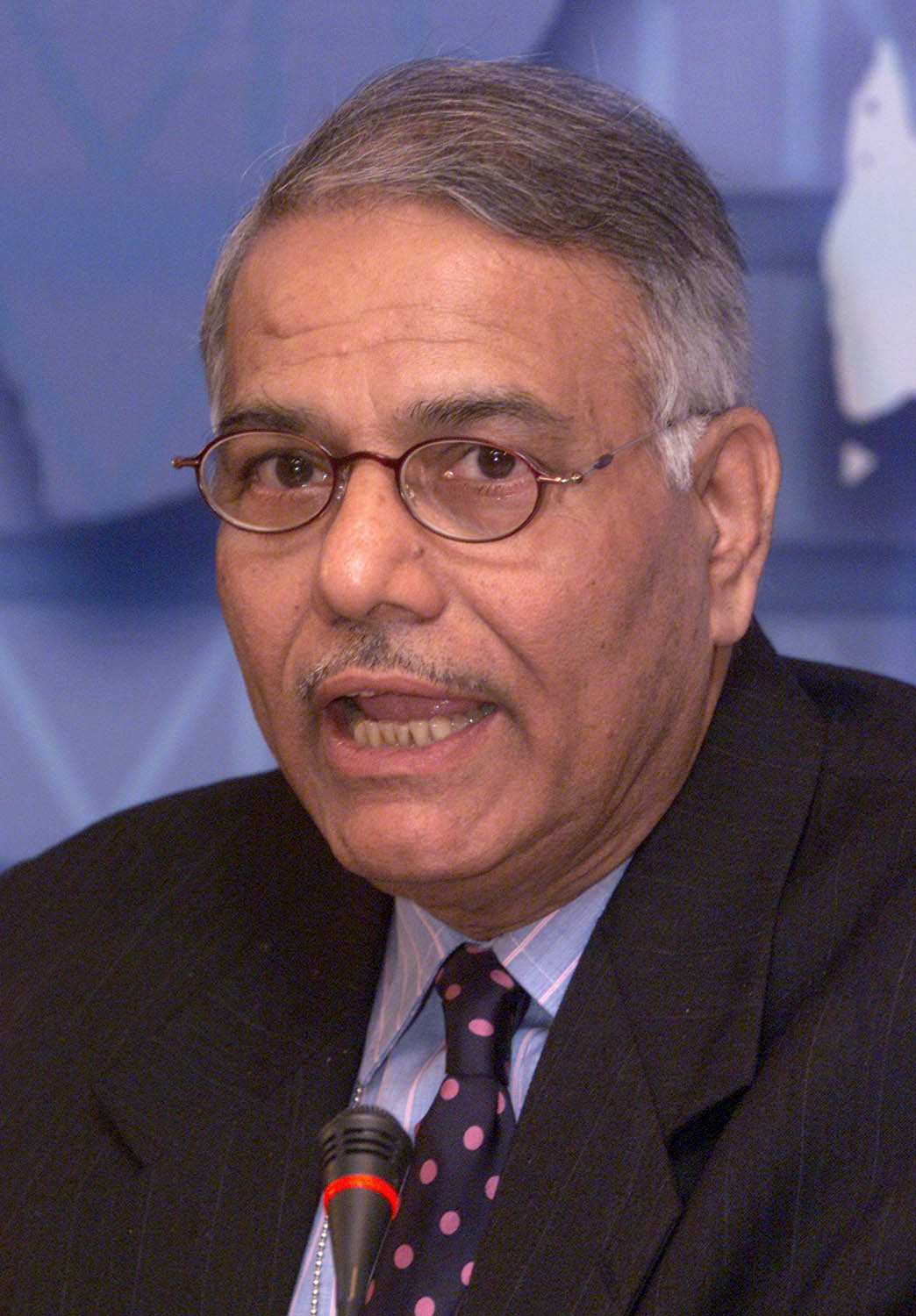

Indeed, Sinha confirms what had been widely rumoured in New Delhi when he was finance minister --- he wasn't particularly close to prime minister A B Vajpayee. In fact, Tarun Das, director general of the Confederation of Indian Industry, the influential business lobby organisation, advised Sinha to see Vajpayee more often. Sinha and the prime minister grew closer later, after Sinha became external affairs minister.

Sinha casts light on several matters.

#V P Singh offered him the governorship of Punjab. Sinha consulted Chandra Shekhar and turned down the offer.

#The Congress party – which was supporting the Chandra Shekhar government from outside --- wanted former finance secretary S. Venkitaramanan to replace R N Malhotra as Reserve Bank of India governor. So Sinha had to ask Malhotra to resign. Venkitaramanan would grapple with a foreign exchange crisis: he told me he'd proposed handing over Indian embassy property in Tokyo and Beijing to real estate developers to net $1 billion.

#P V Narasimha Rao invited him to defect to the Congress party, which had 232 MPs. Sinha was then a member of Chandra Shekhar's Samajwadi Janata Party which had five MPs. Perhaps Rao hoped that other SJP MPs would follow Sinha into the Congress. But Sinha didn't bite. Instead, he joined the BJP.

#Did Manmohan Singh have a memory lapse when he appeared before the joint parliamentary committee (JPC) formed after the Harshad Mehta scam broke? Or did he lie to it?

Sinha was a member of the JPC. He felt that Manohar J Pherwani, who had been appointed chairman of the Unit Trust of India (UTI) by the Rajiv Gandhi government and sacked by the V P Singh government, had indulged in malpractices. The Narasimha Rao government had reappointed Pherwani to UTI.

Asked about this, Manmohan Singh said he hadn't appointed him, his predecessor (Sinha) had. Sinha demanded that the committee call for the file. Singh had signed it.

Incidentally, Pherwani denied any wrongdoing in an interview to me days before he died.

Indeed, Sinha confirms what had been widely rumoured in New Delhi when he was finance minister --- he wasn't particularly close to prime minister A B Vajpayee. In fact, Tarun Das, director general of the Confederation of Indian Industry, the influential business lobby organisation, advised Sinha to see Vajpayee more often. Sinha and the prime minister grew closer later, after Sinha became external affairs minister.

Sinha casts light on several matters.

#V P Singh offered him the governorship of Punjab. Sinha consulted Chandra Shekhar and turned down the offer.

#The Congress party – which was supporting the Chandra Shekhar government from outside --- wanted former finance secretary S. Venkitaramanan to replace R N Malhotra as Reserve Bank of India governor. So Sinha had to ask Malhotra to resign. Venkitaramanan would grapple with a foreign exchange crisis: he told me he'd proposed handing over Indian embassy property in Tokyo and Beijing to real estate developers to net $1 billion.

#P V Narasimha Rao invited him to defect to the Congress party, which had 232 MPs. Sinha was then a member of Chandra Shekhar's Samajwadi Janata Party which had five MPs. Perhaps Rao hoped that other SJP MPs would follow Sinha into the Congress. But Sinha didn't bite. Instead, he joined the BJP.

#Did Manmohan Singh have a memory lapse when he appeared before the joint parliamentary committee (JPC) formed after the Harshad Mehta scam broke? Or did he lie to it?

Sinha was a member of the JPC. He felt that Manohar J Pherwani, who had been appointed chairman of the Unit Trust of India (UTI) by the Rajiv Gandhi government and sacked by the V P Singh government, had indulged in malpractices. The Narasimha Rao government had reappointed Pherwani to UTI.

Asked about this, Manmohan Singh said he hadn't appointed him, his predecessor (Sinha) had. Sinha demanded that the committee call for the file. Singh had signed it.

Incidentally, Pherwani denied any wrongdoing in an interview to me days before he died.

#Sinha and foreign secretary Kanwal Sibal shot down a proposal to return Jinnah House in Mumbai to industrialist Nusli Wadia's mother, Dina Wadia, Muhammad Ali Jinnah's daughter. Vajpayee had cleared the proposal, made by Jaswant Singh, Sinha's predecessor, but Sinha persuaded the prime minister to reverse his decision. Predictably, that put paid to Sinha's friendship with Nusli Wadia.

Though he had Swadeshi sympathies, Sinha was never a member of the RSS. The two didn't agree. He says in the book, “Most of these people were prisoners of an ideology that had long become irrelevant....Unfortunately, it carries great conviction with the gullible, as does the complete nonsense that is dished out by the bhakts on social media these days.”

Sinha rebelled and quit the BJP. Today he stands marginalised. Ministers don't reply to his letters.

This is a good, engrossing book, rich with detail --- sometimes too much detail. Why, for instance, write about so many countries he dealt with as foreign minister? Still, it's a well-edited book. I could spot only one major error --- Dina Wadia wasn't Jinnah's sister; she was his daughter.

The reviewer worked at India Today, was executive editor of a business magazine, resident editor at two financial dailies and a deputy editor at The Telegraph

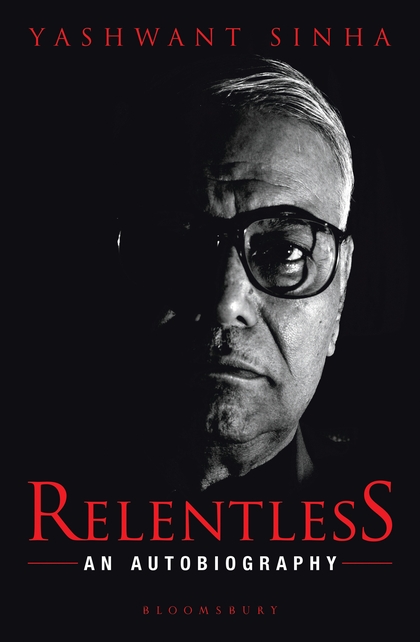

The time: June 1998. The place: a room in Parliament. Finance minister Yashwant Sinha has presented the Budget -- and raised petrol and urea prices. Members of Parliament have erupted in protest. Sinha storms into his room, where I have been waiting to interview him, asks his secretary to get a senior functionary on the phone and explodes into the phone as I am being shooed out.

Sinha doesn't have a thick skin.

In 1967, the Bihar cadre IAS officer was the deputy commissioner of Santhal Parganas district. Irrigation minister Chandrashekhar Singh had shouted at him in public. Sinha protested. Chief minister Mahamaya Prasad Sinha shouted at him and told him to look for another job. Sinha's classic reply: “Sir, I am a gentleman and expect to be treated as one. I am not used to being shouted at. And as far as looking for another job is concerned, I can become a chief minister some day, but you can never become an IAS officer.” Bihar chief secretary B D Pande would later tell him; “Yashwant, in the civil service you must have the skin of a rhinoceros.” Sinha writes, “I have never been able to develop a thick skin, much less one like a rhinoceros.”

Sinha, of course, is no stranger to the public. A poor boy who studied in Hindi-medium schools, he worked hard, taught political science at Patna university, got into the IAS, married an ICS officer's daughter, so marrying into high society (as he puts it). He writes here of life in the boondocks of Bihar, in the bureaucratic worlds of Patna and New Delhi, and of his switch to politics and eventual rise to power. His two political mentors were Chandra Shekhar, in whose short-lived government he served as finance minister, and BJP doyen L K Advani.

Yashwant Sinha's two political mentors were Chandra Shekhar, in whose short-lived government he served as finance minister, and BJP doyen L K Advani Wikipedia