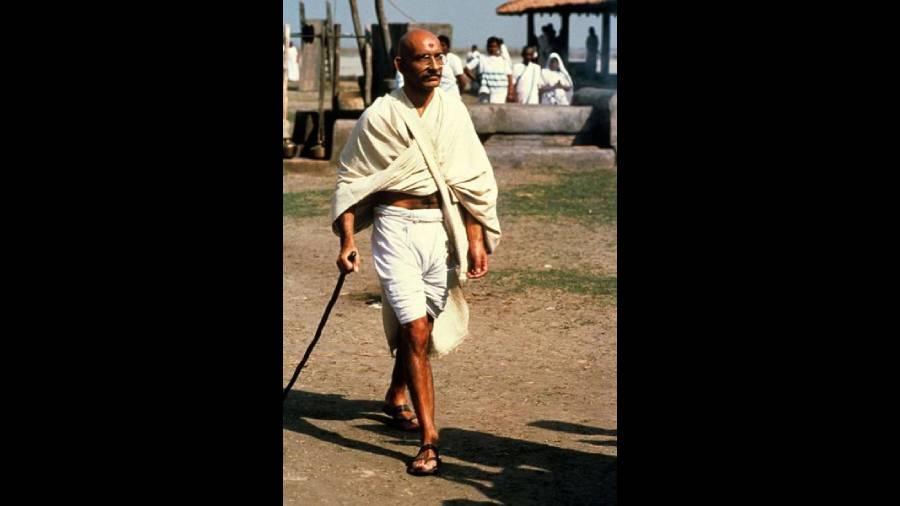

THE MAHATMA ON CELLULOID: A CINEMATIC BIOGRAPHY By Prakash Magdum, HarperCollins, ₹599

When Dino Grandi, the Italian minister of foreign affairs in the early 1930s, disembarked at New York harbour in 1931, he was shocked to see thousands of people waiting to greet him. It was only later that he realised that the unsuspecting New York denizens had confused him for Mahatma Gandhi. Prakash Magdum’s book is full of such delightful tidbits.

Magdum, a civil servant and former director of the National Film Archives of India, thinks like an archivist. His book is thus a rich treasure trove of information on the cinematic representations of the Mahatma for more than a century. It traces the evolution of film-making, from silent films to talkies and from black-and-white films to colour, and shows how Gandhi’s representations changed over time. Magdumstresses how, even though Gandhi shied away and was almost distrustful of film as a medium, early efforts at videotaping his life spread his fame the world over.He specifically details fascinating stories about Gandhi’s first talkie interview in 1931 and the struggles behind the making of the 1982, Oscar-winning film, Gandhi.

However, the book’s greatest shortcoming — this is where Magdum’s instincts as an archivist take over — is that it prioritises information over storytelling. Consequently, reading the book can often be a laboured experience. The pages are filled with detailed descriptions of the different movies that portrayed Gandhi and what Magdum thinks about them. There is very little effort in making a central point or weaving these depictions into a coherent narrative. The book could have also benefited from closer editing and a reduction in length. Yet, its sincerity cannot be doubted.

The kind of things that the book wants to draw our attention to may have been better curated through an immersive website or an exhibition of motion pictures, or maybe even an app! Looking up some of the films that Magdum refers to on the internet brought the book alive.

Another thought that stays with the reader is what does it mean to write a book on the Mahatma today? In a recent essay in Financial Times, Ramachandra Guha reflected on Gandhi’s decreasing relevance in India, arguing that the ideals that Gandhi held dear, such as environmental conservation or religious pluralism, appear to have a diminishing relevance in contemporary politics. He also drew distinctions among idolatry, revisionism or iconoclasm. While this book is mainly an effort in curation, it takes a largely uncritical approach in its praise. What we need is neither idolatry nor revisionism but a more analytical look at Gandhi’s complex legacy. Magdum’s key contribution may have been to draw our attention to an entirely new archive — the motion picture.