|

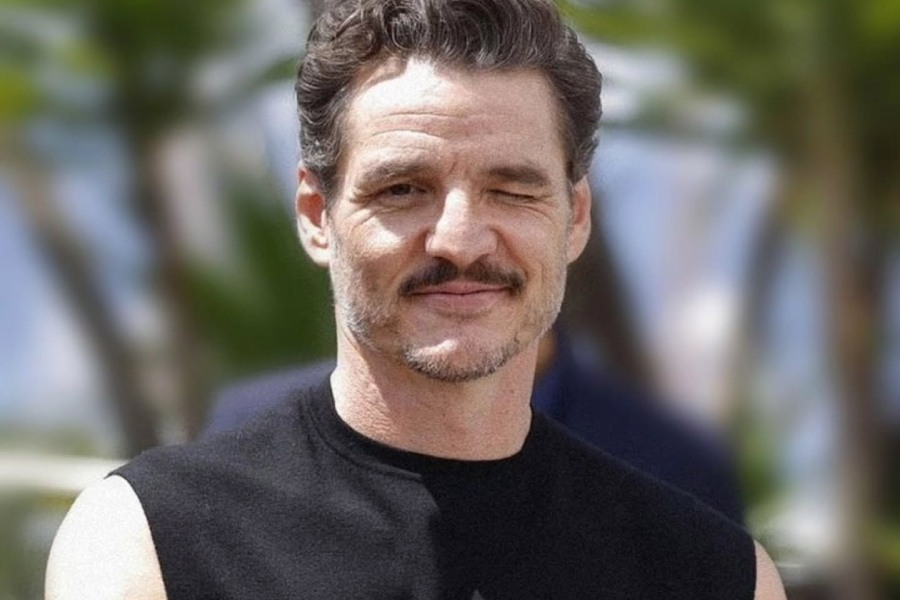

| Francesco Paresce Marconi pays tribute to Jagadish Chandra Bose at Bose Institute on Sunday. Picture by Bishwarup Dutta |

Jagadish Chandra Bose was “out and out a scientist” while Guglielmo Marconi “understood business”, the Italian’s grandson said, crediting both for the first transatlantic wireless communication over 100 years ago that led to the radio.

“A scientist often makes an invention and then moves on, as Bose did. Then it is left for someone else to find a practical and commercial use for it, as Marconi did. They were both much ahead of their times,” Francesco Paresce Marconi said while delivering a lecture at Bose Institute on Sunday.

In the same breath, the grandson referred to other scientists — such as Heinrich Hertz, Oliver Lodge and Henry Jackson — whose work had contributed to Guglielmo Marconi’s achievement.

“Marconi built on the foundation of inventions by many others, assimilated them with his own research and was able to transmit wireless signals over long distances,” said Francesco Marconi, a senior scientist at the Munich-based European Southern Observatory.

The lecture — Marconi, Bose and the Telecom Revolution — was organised to mark the 150th birth anniversary of the physicist-botanist from Bengal.

Guglielmo Marconi had won the physics Nobel in 1909 for the development of wireless telegraphy. But an investigation by the US-based Institute of Electronics and Electrical Engineers — reported by The Telegraph on October 31, 1997 — had proved that the iron-mercury-iron coherer the Italian had used for receiving the first transatlantic wireless message was invented by Bose.

The 68-year-old Francesco Marconi said he believed that his grandfather had interacted with Bose in London in 1897. “Both were there at the same time. They were both foreigners and their research was on the same subject — radio frequency waves,” he said.

“Though I do not have any documentary evidence to prove it, I have a strong belief that they had met and exchanged notes.”

Francesco Marconi, awarded a US patent in 1974 for a restive anode imaging device which is used in research satellites, urged Bose Institute to look for evidence of the exchange in the letters the scientist had written to friends and relatives in Calcutta during his stay in London.

Director Sibaji Raha, however, said his institute did not possess any such letters. “Most of Bose’s papers are in Acharya Bhawan, where the scientist lived. The board of trustees which looks after the building does not entertain our requests to go through the documents there.”