Last year, Ardem Patapoutian got a tattoo. An artist drew a tangled ribbon on his right arm, the diagram of a protein called Piezo. Patapoutian, a neuroscientist at Scripps Research in San Diego in the US, discovered Piezo in 2010, and in 2021 he won a Nobel Prize for the work. Three years later, he decided to memorialise the protein in ink.

Piezo, Patapoutian had found, allows nerve endings in the skin to sense pressure, helping to create the sense of touch. “It was surreal to feel the needle as it was etching the Piezo protein that I was using to feel it,” he recalled.

Patapoutian is no longer studying how Piezo informs us about the outside world. Instead, he has turned inward to examine the flow of signals that travel from within the body to the brain. His research is part of a major new effort to map this sixth, internal sense, which is known as interoception.

Scientists are discovering that interoception supplies the brain with a remarkably rich picture of what is happening throughout the body — a picture that is mostly hidden from our consciousness. This inner sense shapes our emotions, our behaviour, our decisions and even the way we feel sick with a cold. And a growing amount of research suggests that many psychiatric conditions, ranging from anxiety disorders to depression, might be caused in part by errors in our perception of our internal environment.

Someday it may become possible to treat those conditions by retuning a person’s internal sense. But first, Patapoutian said, scientists need a firm understanding of how interoception works.

“We’ve taken our body for granted,” he said.

Everyone has a basic awareness of interoception, whether it’s a feeling of your heart racing, your bladder filling or butterflies fluttering in your stomach. And neuroscientists have long recognised interoception as one function of the nervous system. Now, scientists have powerful tools for studying interoception.

“In the last five years, fundamental puzzles that have been around for 100 years have been solved,” said David Linden, a neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins University, US, who is writing a book on interoception.

To study Piezo inside the body, for example, Patapoutian and his colleagues insert engineered viruses into a mouse organ; the viruses enter the nerve endings that infiltrate the organ and cause the neurons to glow. Close inspection has revealed that the nerve endings use Piezo proteins to detect changes in pressure in many organs.

“Pressure sensing is everywhere in the body,” Patapoutian said.

In the aorta, for instance, Piezo proteins sense blood pressure. In the lungs, they register every inhaled breath. They sense when the bladder stretches as it fills with urine.

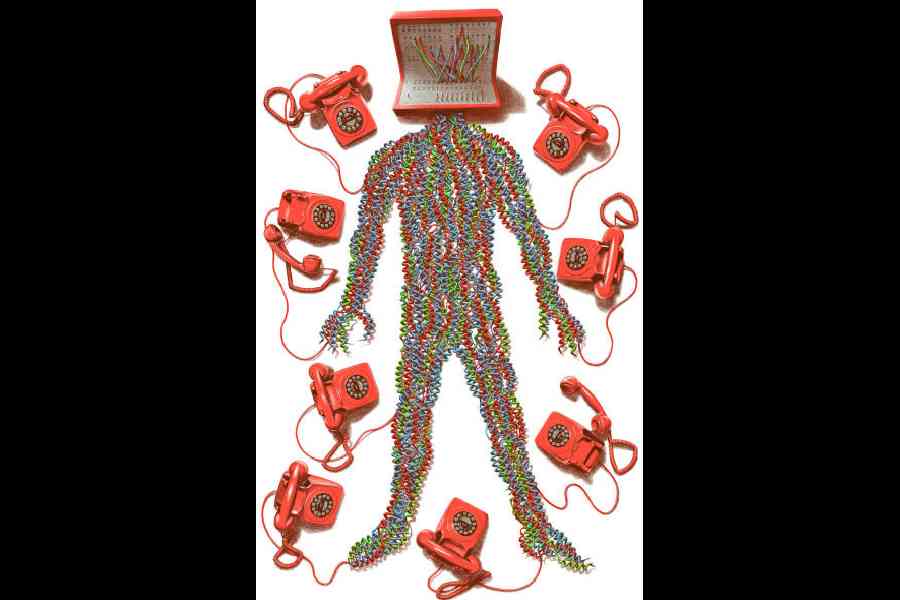

Many of the Piezo-packed nerve endings belong to the vagus nerve, a cable of 1,00,000 neurons that infiltrates many organs. The vagus nerve detects pressure but it also has receptors that register other changes, such as swings of temperature and acidity. In the intestines, the vagus nerve senses sugar molecules and fat in the food we eat — even specific nutrients, such as zinc.

When we breathe in, Piezo proteins sense the stretching of our lungs. The brain responds by stopping the inhalation from overstretching the delicate linings of the lungs. If the vagus nerve detects a toxin in our gut, it can send a signal to the brain that will swiftly cause us to vomit.

In any moment, the brain is sifting and merging signals from all internal corners of the body. How it does so, and what it does with that information, however, remains largely mysterious.

“It’s genuinely overwhelming, and right now our understanding is pretty weak,” Linden said.

Progress has been made recently on at least one puzzle: how interoception makes us feel sick.

“When you feel ill, you lose energy, you lose your appetite, you don’t feel well and you say, ‘Oh, that’s a nasty bug making me feel ill,’” said Catherine Dulac, a neuroscientist at Harvard who studies sickness. “And it turns out that, no, it’s the brain that does that to you.”

As it happens, the brain is constantly monitoring the body for signs of infection. When a pathogen bumps into certain vagus nerve endings, they send signals to the brain. Other nerve endings can recognise the alarm signals that immune cells send to one another.

The brain then creates mental representations of such infections and uses them to fight back. It might raise the body’s temperature, which enables immune cells to fight germs more effectively. It might put the sleep-wake cycle on pause, keeping you in bed to conserve energy. It can even send signals that change the immune system’s assault against pathogens — ramping up an attack here, reining it in there — to minimise collateral damage.

But the brain does more than just react to interoception: it learns from this internal sense and makes predictions that improve our survival.

As vital as interoception is to our survival, researchers suspect that it is also responsible for many disorders. If the brain misinterprets signals from the body, or if those signals are faulty, the brain may send out commands that cause harm.

Increasingly, researchers think that some psychiatric disorders could be treated as disorders of interoception. Patapoutian cautioned that interoception would be hard to harness until it is better understood.

He and colleagues at Scripps Research hope to provide a foundation for such advances by creating an atlas of interoception throughout the entire body.

NYTNS